Nashville historians: Metro is a 'bold experiment' rooted in race-related compromise

At just 10 years old, Linda Wynn, now assistant director for state programs at the Tennessee Historical Commission, had a front-row seat to the birth of Nashville's metropolitan government in the early 1960s. Nashville was in the middle of a post-WWII population boom, school desegregation, lunch counter sit-ins and precarious racial relations.

She remembers her father, a businessman, being in favor of the idea of consolidating Nashville and Davidson County governments due to the expected economic benefits.

"Other members of my family were against the consolidation because they felt that some power would be lost within the African American community," Wynn said Monday during a panel discussion on the role of the Black community in Metro Nashville's creation.

This discussion falls at a pivotal point for present-day Nashville, as Metro government prepares to celebrate its 60th anniversary on April 1 and as state lawmakers proceed with an effort to limit metropolitan council sizes to no more than 20 members.

The consolidation effort was undergirded by the question of fair representation for the Black community, which made up about a third of Nashville's population in the early 1960s. The first attempt, which proposed 21 Metro Council seats, failed in 1958. Metro Nashville's current 40-member council resulted from a key compromise that contributed to the second charter referendum's passage in 1962.

"If that goes back to 20 members, my fear is that African Americans lose representation, at least at the status we have now," Wynn said, noting increased constituencies per district council member would likely lead to reduced access.

More:State Republican leaders want to shrink Nashville's council. Here are the pros and cons.

More:Is 40 members too many? How a smaller Nashville council would compare to others in Tennessee

Consolidation and compromise

After World War II, Davidson County's population expanded rapidly, creating increasing demand for more schools and public services and stretching Nashville's civic resources thin. The city's tax base was eroding, yet county residents commuted to the city and strained its services, according to Davidson County historian Carole Bucy.

The city and county health departments merged long before Metro, introducing the idea of consolidation as a potential solution and "bold experiment," Bucy said. Consolidation supporters included longtime politicians, members of the business community, churches and the League of Women Voters.

But the effort saw opponents, too. The Black community faced several blows to its unity in the form of "urban renewal," the location of the interstates and bearing the brunt of school integration starting in 1957, Bucy said. The prospect of giving up some power in the city to support consolidation left the African American community divided.

After the first effort failed, then-Nashville Mayor Ben West, facing mounting needs for education and services, attempted to achieve consolidation through other means. He began annexing parts of Davidson County and instituted a controversial wheel tax, angering county residents who commuted to the city for work. These issues sparked a second try at creating a metropolitan government.

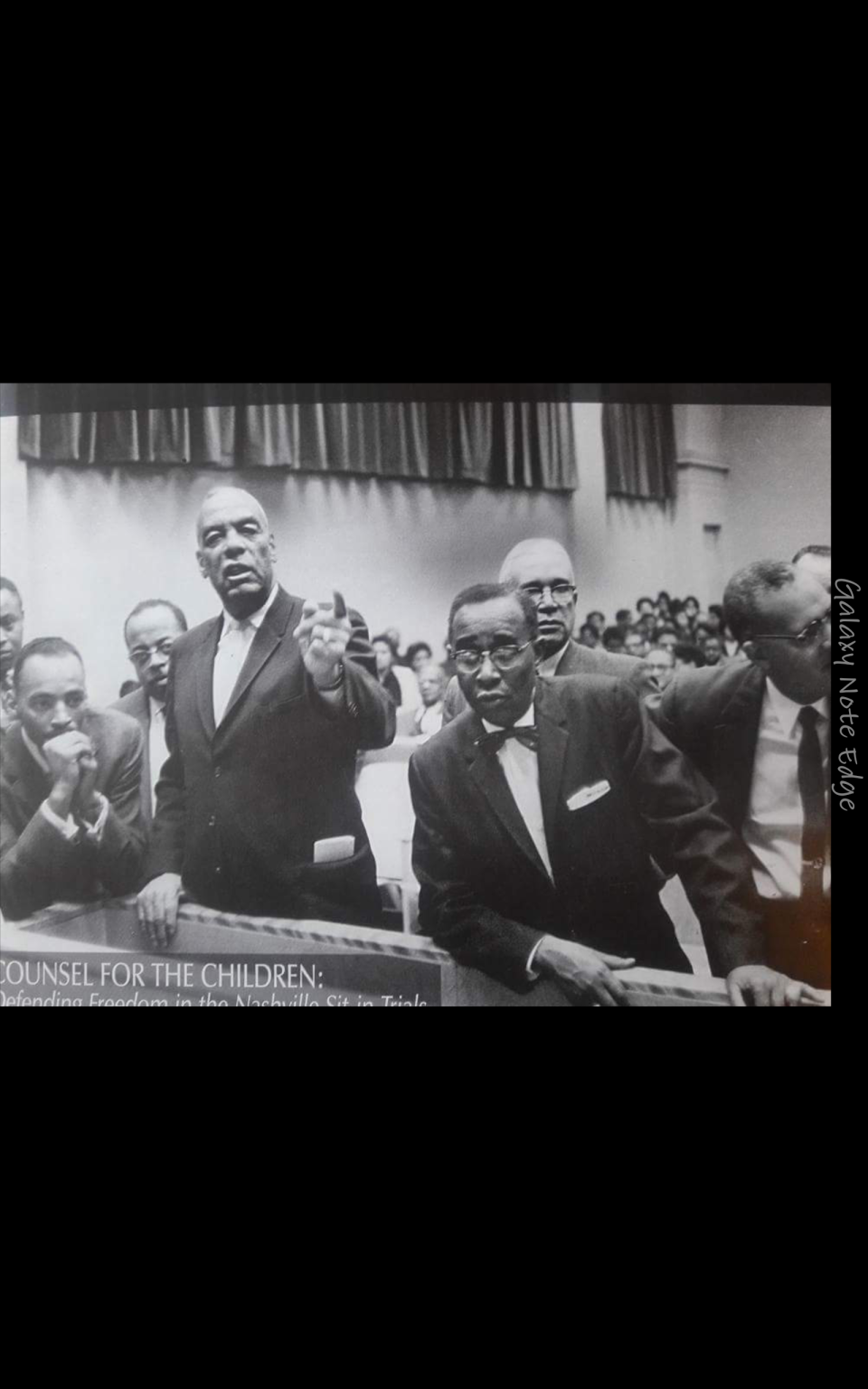

Robert Lillard, an attorney and then-city council member representing South Nashville, staunchly opposed the idea, believing Nashville's Black community would lose hard-won political gains in the unification. But Z. Alexander Looby — a prolific civil rights attorney, member of the consolidation commission and also a then-Nashville council member representing the more middle-class area around Jefferson Street, Fisk University and Tennessee State University — pushed hard to make a metropolitan government happen.

"Z. Alexander Looby ... fought very hard to make sure that we had a supply of council members ... to ensure that (Black residents) were represented across the city under the new Metro government," said Edward Kindall, an attorney, author, and former school board and council member.

The 35 council district seats were most important to Looby, according to longtime Nashville political analyst Pat Nolan, who also spoke on the panel. Looby didn't speak much on the five at-large seats, because at the time, "at-large representation was clearly seen across the South ... as a way of diluting or actually wiping out Black representation."

Other compromises included the creation of the General Services and the Urban Services districts to institute different service and tax levels. Six incorporated communities within county limits were allowed to keep their charters.

The consolidation of the school board was also an issue of intense discussion. Members of the charter amendment commission were divided over whether the school board should be appointed by the mayor and approved by the Metro Council or elected, Bucy said. A charter amendment for an elected school board passed in a referendum triggered by a public petition during former Mayor Richard Fulton's tenure from 1975 to 1987, Nolan said.

About 45% of the area's Black population voted in favor of consolidation in 1962, enough to push the measure through. Looby and Lillard, who "yielded to the wishes of the majority," served on the new Metro Council alongside three other Black representatives.

"Since then, I think most African Americans believe that was the right thing to do," Kindall said. "I certainly do at this time."

Cassandra Stephenson covers Metro government for The Tennessean. Reach her at ckstephenson@tennessean.com. Follow Cassandra on Twitter at @CStephenson731.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Historians: Metro Nashville's creation was rooted in race-related compromise