The National Park Service put a historic Fall River anti-slavery landmark on the map

FALL RIVER — A historic home on Pine Street has been nationally recognized as a station on the Underground Railroad, the network of safe-houses in the mid-19th century whose owners sheltered Black people escaping slavery to freedom in Canada.

The National Park Service on Tuesday added the Dr. Isaac Fiske House at 263 Pine St. to its list of sites on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The house, built in 1833, is owned by the Preservation Society of Fall River, which has plans to open a portion of the house as a museum.

The NPS’s Network to Freedom is a collection of more than 700 places nationwide that played a role in the abolition of slavery. The Fiske House is the first Fall River site to make the list.

“The Fiske House is one of several Underground Railroad sites in Fall River, but none had received the Network to Freedom designation,” Preservation Society President James Soule said. “We at the Preservation Society are excited that the Fiske House is the first in the city to be added to this prestigious network, and we are hopeful it’s not the last.”

6 homes part of Black history: Fall River was an Underground Railroad junction. Where were the stations?

What was the Underground Railroad?

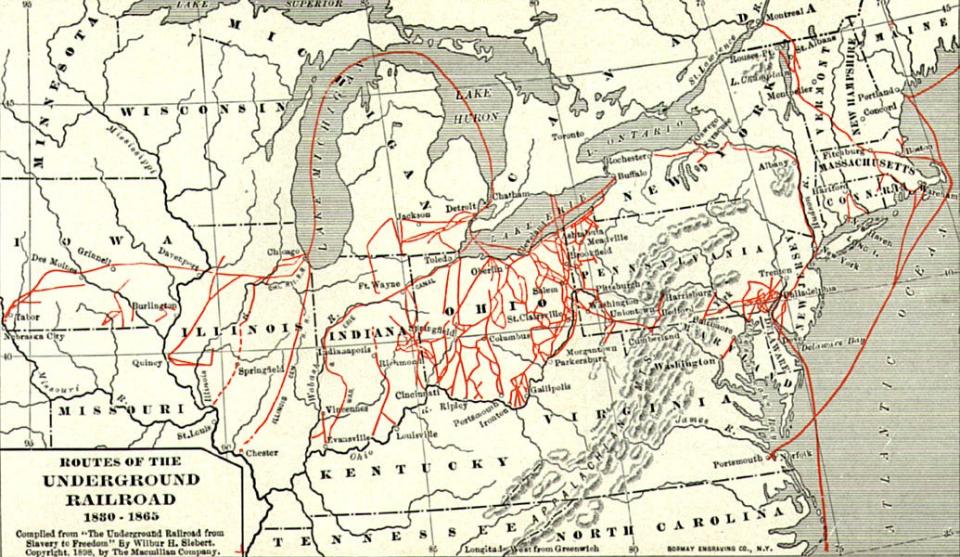

For several decades in the early 19th century until 1865, Fall River was an important stop on the Underground Railroad. For generations, Black people had been kidnapped from Africa and forced into involuntary servitude on Southern farms. Runaways bold and lucky enough to escape could find help from free Black people and white people opposed to slavery. From Norfolk, Virginia, Black fugitives stowed away on commercial ships to Wareham or New Bedford. From there, conductors brought this “cargo” to Fall River, kept these people hidden from police, and guided them on to Rhode Island and eventually Canada where slavery had been abolished.

Underground Railroad conductors were criminals breaking the Fugitive Slave Law. The white conductors risked steep fines and imprisonment. The Black people fleeing the South risked being sent back to the hell of slavery and likely punishment that could have meant whipping, branding or mutilation.

Because of the secrecy involved, it will never be known for sure how many Black people passed through Fall River, or even exactly how many stations there were.

More Fall River history: The Lizzie Borden House has undergone restorations and upgrades. Here's what's new.

Who was Dr. Isaac Fiske and what happened in his house?

Fiske was a Quaker who studied medicine and taught penmanship for many years. He owned a private boarding school in Scituate, Rhode Island, for 10 years, then settled in Fall River to practice medicine as a homeopath. He lived in the home with his wife, Anna, and two children, George and Anna.

Like many Quakers, Fiske was also a staunch abolitionist on ethical and religious grounds. He published articles in publications including The Liberator, was involved in many anti-slavery meetings and societies, and in 1861 led a petition to have Fall River end the practice of hunting for freedom-seeking Black enslaved people.

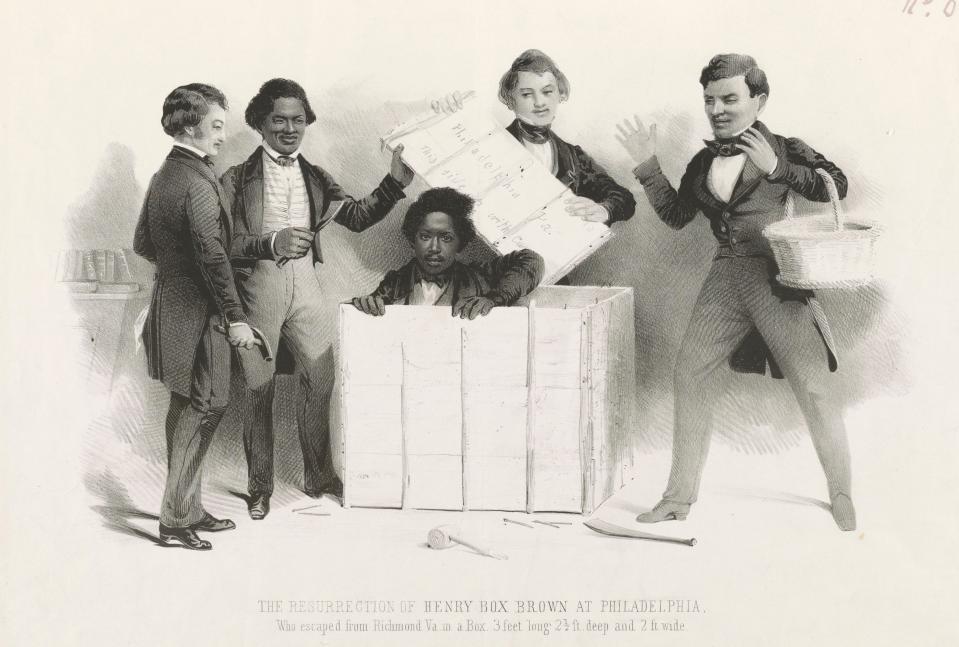

According to letters written by his daughter, Fiske used his Pine Street home as a way station for slaves, noting that when she came home from school “there might be an escaped slave at the house on his way north to freedom in Canada whose presence must be mentioned with bated breath.” Legend has it that at one point Fiske hosted Henry “Box” Brown, a runaway who escaped a Virginia tobacco factory by mailing himself in a wooden crate to Philadelphia in March 1849, and made his way to Boston. According to Soule, Brown may have made part of his journey north on a Fall River Line steamship from New York.

Saving old structures: From churches to mills, these 13 places in Fall River are at risk of losing historic value

What is in the Fiske House now, and can I visit?

The house passed to many different owners through the generations, but the Preservation Society bought it in 2018 and has been in the process of restoring it with help from the Community Preservation Act. Today, the house is a rental property, home to seven tenants and not open to the public.

But the Preservation Society is hoping to change that. They’re currently in the process of restoring the home’s basement, where Fiske had his medical practice, with the goal of using the space for a public museum to Fall River’s role in the abolitionist movement.

What does the National Park Service’s announcement do?

Monday’s announcement doesn’t make the Fiske House a national park — it validates all the research done into the house’s slavery-era history, paving the way for future museum space. That research was performed by the Preservation Society, historian Kenneth Champlin, the Fall River Historical Society, and student researchers from Roger Williams University, who recently gave a talk about their findings.

“Each addition to the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom centers around a story of hope in the face of hostility and oppression," said Diane Miller, the network’s program manager.

What other Network to Freedom sites are there locally?

New Bedford has four sites on the Network to Freedom, including the Sgt. William H. Carney House, home of escaped father and son fugitives who arrived from Virginia in 1857 and 1859. Carney enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the nation’s first all-Black Army regiment, which fought in the Civil War and whose story was told in the film “Glory.”

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: National Park Service adds Fall River home to Underground Railroad map