National Wake: the multiracial South African punk band that rebelled against apartheid

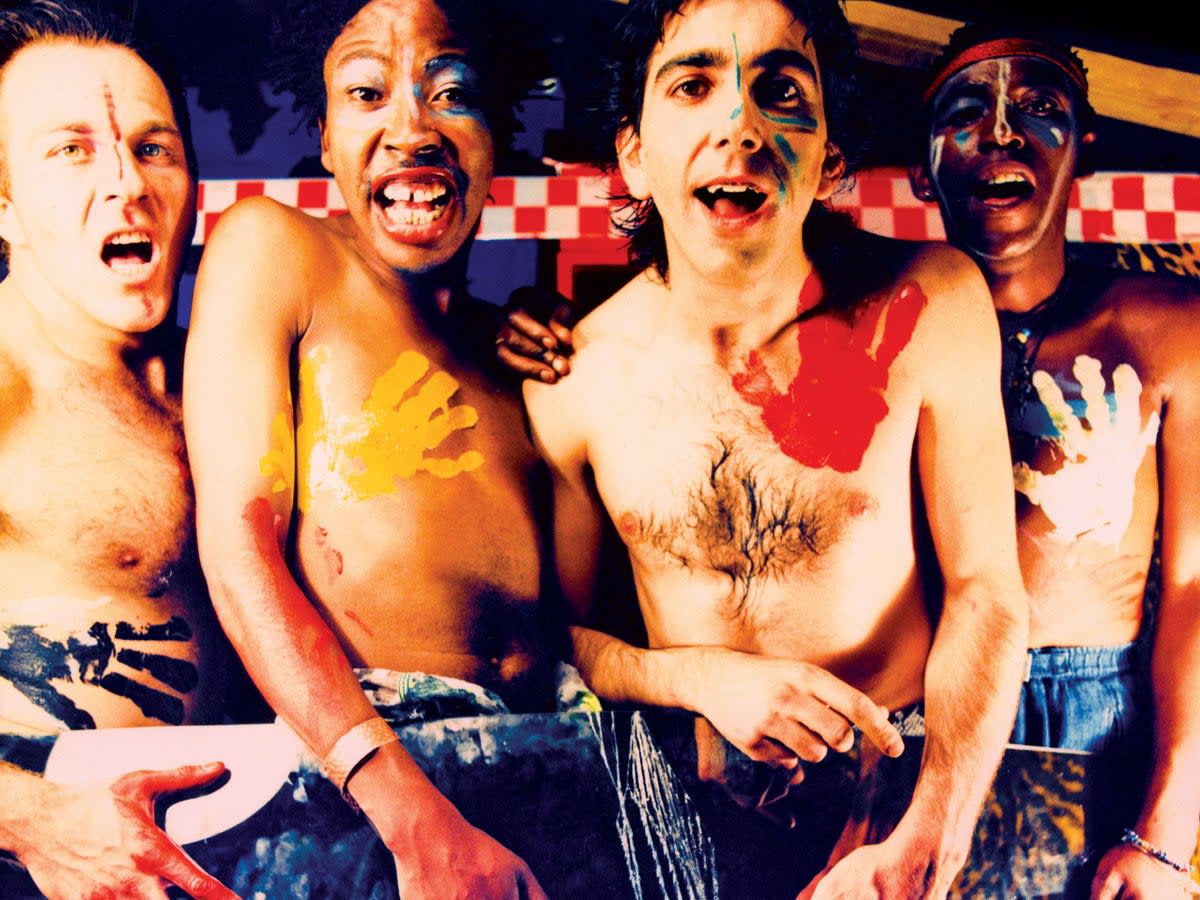

Guitarist and songwriter Ivan Kadey didn’t set out to form South Africa’s first multiracial punk band, but from the moment he met brothers Gary and Punka Khoza it was clear what a potent combination they would make. In the late Seventies, under the apartheid system of institutionalised racial oppression that kept white and Black South Africans apart, the group’s very existence would prove explosive. “Just standing up and making music together was a political statement,” explains Kadey, now 70, speaking over video call from his current home in Los Angeles. “We were for a non-racial, peaceful South Africa and just by getting up and performing we stood for that. On many levels, it was a f*** you to the system.”

He already had the perfect name for this band of outlaws: National Wake. At the time the country was under the rule of the right-wing National Party, so by calling themselves National Wake they were both urging their country to wake up from the nightmare of segregation and promising to celebrate its demise. “We were saying: ‘Let’s dance on the corpse of apartheid,’” explains Kadey. “The name was a pure agitprop statement, as was the very composition of the band.”

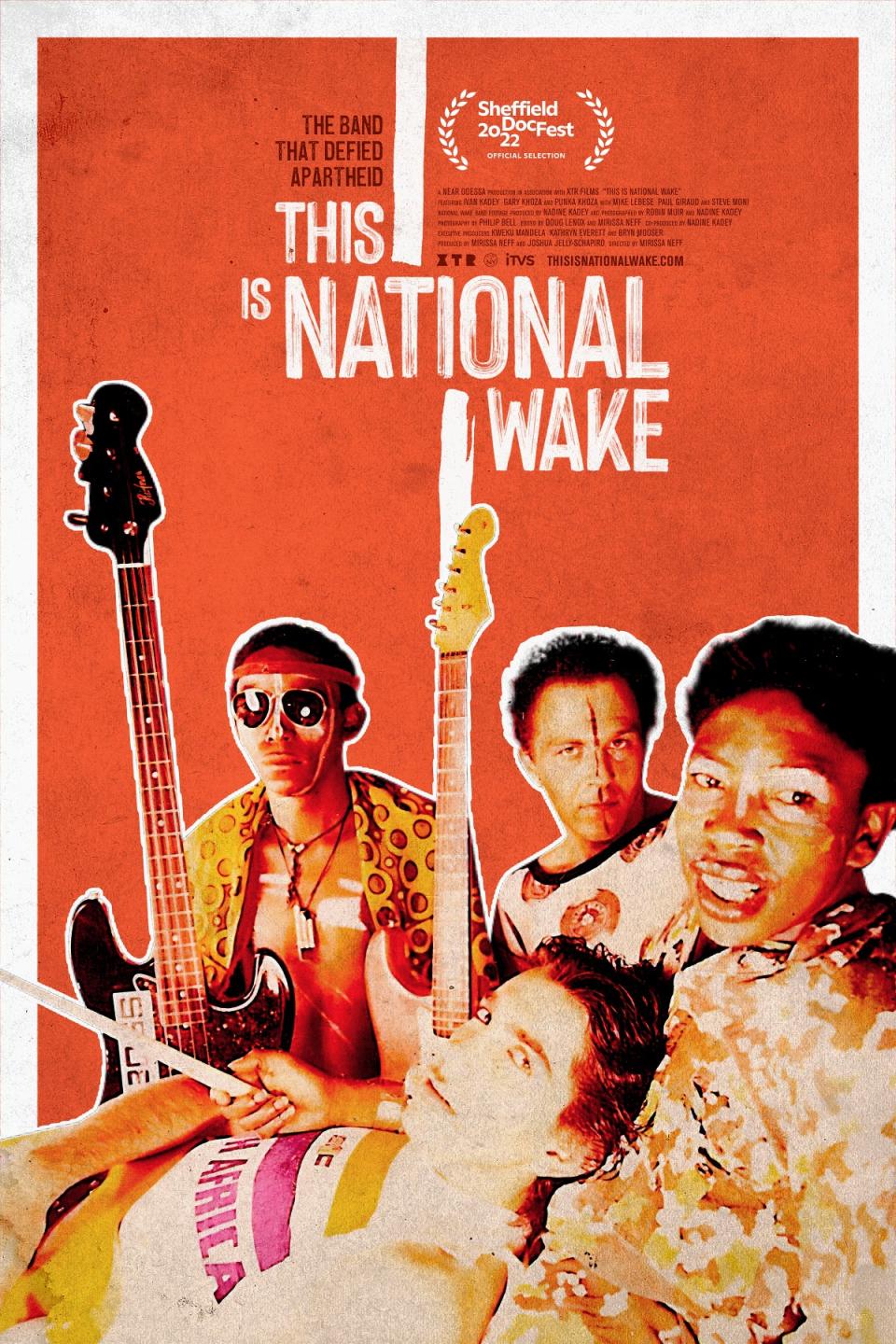

Formed in 1979, National Wake recorded just one album before splitting under the pressure of police harassment in 1982. Now the story of their brief, turbulent existence is being told in a new documentary, This Is National Wake, which has its world premiere this week at Sheffield DocFest. Director Mirissa Neff believes the band’s story remains powerfully resonant. “One of the major themes of this film is about how we experience history,” says Neff. “This band came from a particular moment in time, a police state where these godawful, inhumane things were happening, and they converted that into something beautiful. These were people who were not even supposed to be together, yet they formed for the love of music across race lines when it was illegal to do so. I think that’s so admirable.”

In 1976, Kadey, the orphaned son of Jewish immigrants, was an architecture student living in a communal house in Johannesburg when the city was rocked by the Soweto uprising, a demonstration led by Black students, which ended with a brutal police crackdown that killed at least 176 young people. “Students were putting their lives on the line to protest government oppression,” remembers Kadey. “It made one reflect: what were you prepared to do? What were you doing in relation to the struggle? For myself, music was the most immediate form I could use to express my feelings about living in South Africa.”

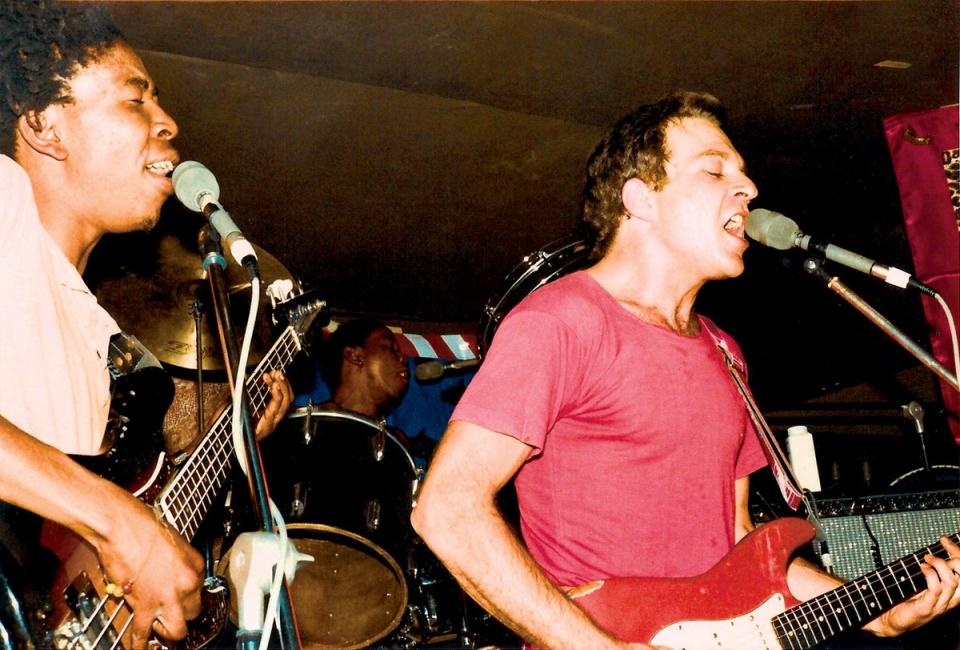

Over the next three years Kadey played and wrote songs with his friend Mike Lebesi, but what they really needed to start a band was a bass player and a drummer. “We went through all sorts of people jamming with Mike,” remembers Kadey. “Eventually he said: ‘Hey, I’ve got these two buddies from Soweto. It’d be great if they came over and we had a jam’ and that was it.”

Gary and Punka Khoza turned out to be just the people Kadey was looking for. Gary, the older brother, was a softly spoken introvert who had been a musical prodigy in his youth. “The story goes that Gary was discovered at the age of nine in a courtyard in Alexandra township, playing drums on biscuit tins,” explains Kadey. “From the age of 10 he was drumming for the Flaming Souls, who were a really hot soul band at the time. He could play any instrument backwards, forwards and sideways.” He became National Wake’s bassist, while his charismatic younger brother Bernard ‘Punka’ Khoza took up the drums. Together they formed a powerful rhythm section that provided the engine for urgent protest songs like “International News”, about the media blackout surrounding the townships and the war in Angola.

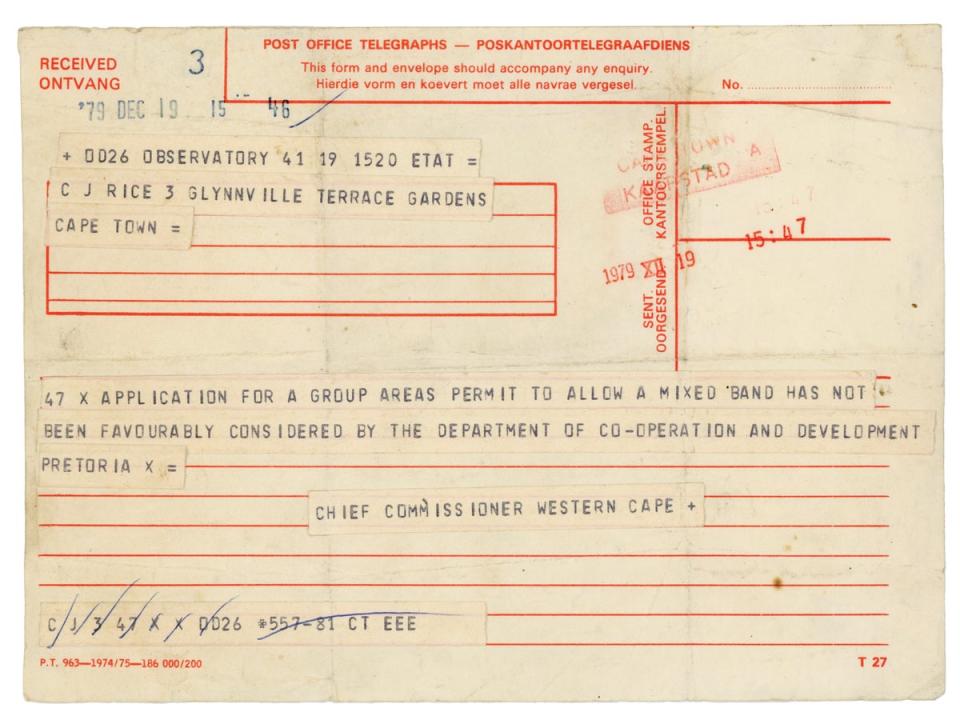

National Wake quickly earned a following in Johannesburg, playing semi-legal shows at student unions and some segregated venues. But when they tried to join a national tour called Riot Rock in December 1979, playing alongside all-white punk and new wave bands like Wild Youth and The Safari Suits, the promoters received a stark message from authorities telling them that a “permit to allow a mixed band has not been favourably considered”. The band were determined to play anyway, but in the conservative town of Fish Hoek the promoters lost their nerve and pulled the plug on the band seconds after they walked onstage. It was just one of many such frustrating experiences for the band. “Look, the Wake wasn’t glamorous,” says Kadey. “It wasn’t like we were on top of the world floating on a sea of fans. It was a struggle, just as the whole apartheid resistance movement was a struggle.”

The constant uncertainty about whether they would be allowed to play or not weighed on the band. Original lead guitarist Paul Giraud left because, as Kadey puts it, he “found dealing with the Wake too much of a strain. You had to be of a certain capacity to handle what it was.” He was replaced by The Safari Suits’ Steve Moni, who had witnessed the controversy around National Wake on the Riot Rock tour. Moni, who joins the video call from his home in Prague, says the prospect of joining the band was both “extremely exciting and extremely challenging”. He adds: “It was much more than just a band. It was a lifestyle. It was a prototype.”

While there were other multiracial musical acts in South Africa at the time, including jazz bands and folk groups like Juluka, whose white frontman Johnny Clegg sang in Zulu, they weren’t pushing the same sort of countercultural messages that National Wake made the core of their identity. “What was incredible about the Wake,” says Moni, “was that it really was something that hadn’t been seen before.”

The band’s sole self-titled record was released in 1981, selling somewhere in the region of 700 copies before it was withdrawn under government pressure. “Very soon after [record label] WEA International put the album out, the security police arrived and basically told them to shelve it,” remembers Kadey. “They withdrew it and stopped promoting it, not that they ever did much of a job of promoting it!”

The release of the album was just the excuse the police needed to step up their harassment of the band. By this point, Kadey’s home had become National Wake headquarters and was subject to multiple daily searches by officers looking for cannabis and “subversive literature” as well as other pretences for an arrest. One day the band were summoned en masse to a local police station. “There was this little guy in grey flannel pants, a tweed jacket and a little Hitlerian type moustache,” remembers Kadey. “He said: ‘What are you doing?’ I said: ‘We’re a band. We make music. We want to sell records.’ I never mentioned politics. I just spoke about our ambitions as a band. He looked at us and said: ‘There’s no place for you here. You should go overseas. Call yourselves ‘Exile’, you’ll do really well.’ And then he let us go. It was all very ominous.”

The pressure of trying to make it as a band in such oppressive circumstances eventually led National Wake to split and go their separate ways in 1982. For decades their story was largely forgotten, and tragically Gary and Punka Khoza died before interest in the band was reignited by 2012 documentary Punk In Africa and the 2013 compilation Walk In Africa 1979-1981, which brought together live bootlegs and original National Wake recordings. This is National Wake is the first time the group’s inspiring story has ever been told in full. “The Wake was like lightning in a bottle,” says Kadey. “It happened over a period of two or three years and then it lost oxygen and died. I think Mirissa’s movie is going to breathe fresh life into it. Forty years since the band broke up, it still feels like something that was amazing to be a part of.”

Kadey hopes their defiant tale can help inspire a new generation to speak out about what they believe in, and to channel their rage and frustration into making their own incendiary music. “People were looking for a peaceful, non-violent solution to what was happening in the country, and the Wake was that,” he says. “It was a way of defying all the laws in a way that said: ‘Hey, we can come together and make something coherent and powerful.’ You could dance to this f***ing thing. It was primarily shake-your-ass music. There weren’t many ballads.”

This Is National Wake premieres at Sheffield DocFest on Friday 24 June and screens again on Monday 27 June. More info at thisisnationalwake.com