Work by Native American artists fills this Austin gallery's walls

Damian Charette said being an artist “was like a sickness” he couldn’t help.

It infected him at a young age, leading him to doodle on worksheets at school — and then get in trouble for them.

That "sickness" eventually landed Charette a spot in Austin’s WYLD Gallery, which strictly features Native American art.

Ray Donley, 67, founded WYLD Gallery, located on Springdale Road, in late 2019. He’d recently retired from his career as a lawyer and had a large collection of Native American art, which he started accumulating in the 1980s after a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Donley’s grandfather is half Chickasaw, but Donley does not identify as Native American and says he’s “not the right person to talk about” Indigenous culture. But through WYLD Gallery, he created a platform to help Native American artists of various tribes discuss their heritage and history.

These artists include Damian Charette, Joyce Nevaquaya Harris and Travis Mammedaty.

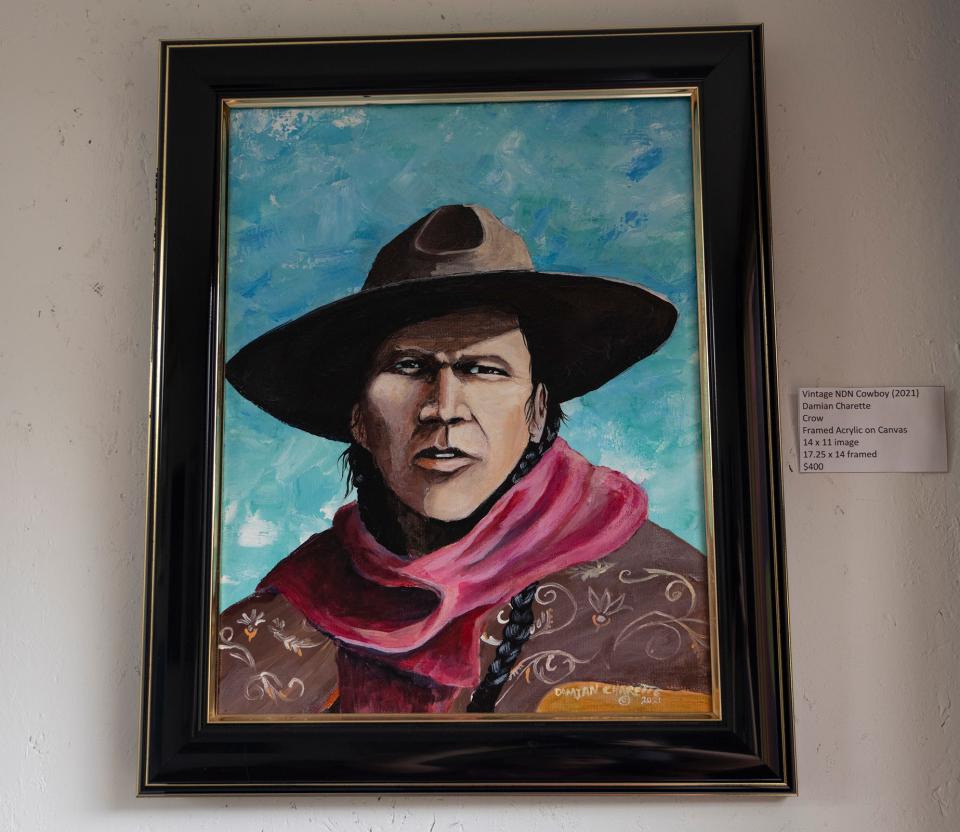

Damian Charette

At a junior high school in Montana, a teacher from the Sioux tribe didn’t see trouble in Charette’s doodles. He saw the artistry, and he helped foster it.

Charette ended up falling in love with printmaking and then painting, and he realized art helped ground him and explain to others what it meant to be Native — specifically Crow.

The Crow are a Native American people mostly concentrated in Montana, where Charette grew up on a reservation. He described the Crow as people who pride themselves on their language, horsemanship, warrior ancestry and appearance.

“We have a clan system still, and we live by our clan,” Charette said. “So you learn who you are and who's in your clan and who your clan leaders are. And I guess a lot of tribes don't have that anymore … but it's something very strong and something that we grew up in. We are matrilineal … so we follow our mom’s family, our mom's clan. For the rest of our life, that's who we are.”

More:These are the Statesman's 10 favorite movies of 2022

Charette, 62, now lives in San Antonio with his girlfriend. He’s lived there about six years, and though he travels to Montana in the summer, he said he misses his home. He’s found himself leaning into his girlfriend’s Mexican culture, finding similarities to his own heritage there.

“I'm pretty sure a lot of people here in Texas have never heard of the Crow tribe before,” Charette said. “Texas does not have a lot of different Native American tribes here, or the number of Native Americans here are very limited. Say, Arizona, New Mexico, Montana, Wyoming — you see them every day, and you hear the language spoken every day. Here in San Antonio, no. You don't hear it. You don't see it.”

In his work, Charette explores aspects of Crow culture such as the sweat lodge, which he says is their church, and peyote ceremony, which is for healing. He dives into the meaning, feeling and imagery of those spaces and events, and some pieces tap into the intersection of opposing elements.

“A real famous piece that I did was called ‘Caddy Indian,’ and it was my grandmother's 1963 Cadillac parked in front of the tipis with my uncle, who was getting ready to go to the rodeo,” Charette said. “And you can see his boots as he's sleeping in the front seat of the Cadillac — you can see his boots on the window.”

Though Charette is a full-time artist, the Parkinson’s disease he was diagnosed with last spring impacts some aspects of his work. The diagnosis was recent, although he said he’s dealt with the effects of the disease for about seven years. These effects include issues with memory and motor skills, leading him to accidentally smear a canvas with paint and to look at the sharp tools used for woodcutting — a printmaking technique — with hesitation.

He said he’s trying to create and photograph as much art as he can right now. There are so many more parts of the Crow culture that he wants to put into art, and regardless of his progressing Parkinson’s, Charette is determined to make it happen.

“Being an artist, it's up to me to find a new way to express myself,” Charette said. “And I'll figure out a way. I mean, if I'm painting with my feet, then that's what I'm doing. Maybe I move to a different medium that is easier to control. I've always found a way to overcome my hurdles, and art's always been there for me, so I don't see a problem.”

Joyce Nevaquaya Harris

When Nevaquaya Harris was a child, her father would sit her down and tell her stories about their Comanche culture, stories with horses and hummingbirds that instilled a sense of pride. Those stories wove their way into artwork Nevaquaya Harris created — her artistic talent serving as another piece of her identity that her father passed down.

“I'm a self-taught artist. I've never had any lessons,” Nevaquaya Harris said. “Just being around my father, I would go and just watch him draw or paint, and so I believe that it was something that was a gift that I inherited from him.”

Nevaquaya Harris’ older brothers were also artists, and she looked to them for guidance on what materials to buy. She ended up using acrylic paint, first with regular paint brushes and then experimenting with non-traditional tools such as a palette knife.

Just last year, the Oklahoma artist created an acrylic on canvas piece titled “Peace of Mind.” The painting depicted her sitting alone with a blanket wrapped around her, the wind blowing her hair and a hummingbird floating nearby. The U.S. Department of the Interior Museum in Washington, D.C., purchased the painting, and Nevaquaya Harris thought the painting would be housed there. But it went somewhere even more special.

More:'It's just so beautiful': Austin Powwow celebrates Native American heritage, history

“Maybe a few months later, they sent me an email and told me that the painting that they purchased was inside of the secretary of interior's office,” Nevaquaya Harris. “And so I was like, ‘What?’ I was really thrilled. … I couldn't believe it, because I've only been into my career for maybe seven years professionally. I guess you could say professionally, but this is who I am and … it's just something natural that came upon me.”

Deb Haaland, the secretary of the interior, is the first-ever Native American cabinet secretary.

Now 58, Nevaquaya Harris continues to use artwork to express her identity, which includes not just her enrollment with the Comanche Nation but her descendancy from the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Crow.

“(My father) would always instill that, you know, to be proud of who we are and where we come from,” Nevaquaya Harris said. “And so as I grew up, going to public school, I kept that in my heart and my mind. And I always knew that I was different. But my art, I believe that it reflects who I am.”

Travis Mammedaty

A job breaking down exhibitions at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, fanned a flame of artistic passion within Mammedaty.

It was a flame that had stayed dormant for years. He’d always enjoyed art — and history, hence his job at the museum — but he’d never fully explored his talent. Before that job, drawing didn’t even serve as a hobby for Mammedaty. He said he was “just playing around” and then throwing out whatever sketches he came up with.

But with every exhibition Mammedaty cleaned up, his interest in pursuing art grew. He said he saw many Kiowa names next to the art on the walls, which stuck out to him because of his Kiowa heritage. He’s also from the Cayuga Nation of the Seneca-Cayuga.

“I started sort of drawing more and then started getting involved with painting and things like that and working in that kind of medium,” Mammedaty said. “And then it was just like from that point, it was something I wanted to do.”

The 40-year-old artist, now living on a reservation in Arizona, said he’s developed a kind of contemporary expressionist style since he began seriously pursuing art in 2017. He uses bold colors and brushstrokes with acrylic paint, though he sometimes works in charcoal.

Mammedaty said he draws on both sides of his heritage in his work. For the Seneca-Cayuga, he’ll sometimes create a depiction of a longhouse. For the Kiowa, he’ll look to their history of tipis, buffalo hunts and horseback riding.

“That's kind of like the type of stuff that I paint, but I paint it in a vivid, colorful, abstract, expressionistic type style to where it's still linked to that past and that I'm drawing inspiration from it, but from my own way,” Mammedaty said.

But no matter his source of inspiration, Mammedaty finds himself mostly painting portraits — often of no one in particular. He simply follows where his brush takes him.

Mammedaty hopes to one day open a gallery space where he can host little-known artists, as well as workshops and language panels. Mammedaty is a Kiowa language instructor, and like art, language helps him express and preserve his culture.

“Your stories, your ceremonies, all that stuff revolves around your language,” Mammedaty said. “If you go into a sweat lodge, you go into a tipi to pray … to ancestors from a long time ago, they didn't speak English. They speak Kiowa. So it's really important to keep those things going.”

(UPDATE: Damian Charette's first name was incorrect on first reference in two earlier versions of this story.)

If you go: WYLD Gallery

The gallery is at 916 Springdale Road in the Canopy complex. It's open on the first Saturday of the month and by appointment. Contact owner Ray Donley at ray@wyld.gallery or 512-657-6583. More info at wyld.gallery.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: WYLD Gallery at the Canopy Complex spotlights Native American art