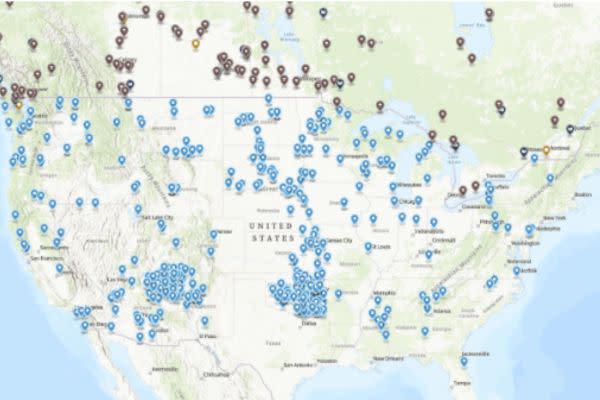

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition Launches Interactive Map of United States’ 523 American Indian boarding Schools

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) has launched an interactive map of American Indian boarding schools and residential schools in partnership with the National Center on Truth and Reconciliation.

The map chronicles the locations and basic information of 523 such schools in the United States, as well as more than 130 residential schools in Canada. Many of these schools — in particular boarding schools active between 1819 and 1969 — engaged in forced and frequently brutal assimilation of Native students, according to a 2022 report by the Department of the Interior.

Seeing more than 500 dots spread across the country was an emotional moment for Deidre Lyn Whiteman, director of research and education for NABS.

“I still get overwhelmed when I see the map. More than likely there's cemeteries connected to these dots. There are graves next to these places. That's what really saddens me, when I look at it and think about that more,” Whiteman told Native News Online. “...it's a tool that's going to be useful to all of our relatives, and our communities and our families.”

The map pulls together “thousands of hours” of work by a staff of less than 20 NABS researchers in partnership with the Department of the Interior in cataloging schools, said NABS CEO Deb Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribe in Washington.

“It's an emotional day, definitely, and our team has put in years of work to get to this point — with little to no cooperation from some of these institutions that took these children,” Parker said. “I really applaud our staff for their tireless work.”

The organization’s initial list of 367 schools, released in 2021, swelled to 408 through a study by the Department of the Interior. Then, NABS found another 115 through continued research on schools managed by private or religious groups.

Those have been subsequently mapped into a set of clickable entries that produce a short history of each school, including years of operation, any other names the institution might have used as well as funding and management entities. The map therefore represents NABS’ most recent data, Parker said, but by no means complete data.

“Because of all of these research gaps and the lack of funding, we believe that there are other schools out there that we are interested in learning about, so this is up to date as far as our research has provided or gotten us, and we would love for others to join us in this movement to help us create the most inclusive map possible,” Parker said. “It’s ongoing work.”

This isn’t the only planned project under the NABS banner. The group plans to launch a database with nearly 50,000 records collected from boarding and residential schools to assist family members in further researching their loved ones and their stories. That database should be coming in November, Parker said.

It’s another step towards reconnecting families with those lost to a brutal system, said Whitehead, and beginning a long-due healing process.

“I've learned more over the years about certain family members and their stories. It's been heartbreaking in that aspect to be continuously reminded about what our relatives went through,” Whitehead said. “It's also been healing to navigate that - there's nothing wrong with me, there's nothing wrong with my family. There were these systems that were pushed on us, but it's just a good understanding that this was placed upon us.

"I just hope that this shows other Native families that they can start their healing process by looking at these schools. Others can start their own research and their own tools to look into the past - what happened to their relatives, what happened at these schools, to understand and ask those questions and to dive deeper into those histories.”

About the Author: "Chesley Oxendine (Lumbee-Cheraw) is an Oklahoma-based reporter for Native News Online and its sister publication, Tribal Business News. His journalism has been featured in the Fort Gibson Times, Muskogee Phoenix, Native Oklahoma Magazine, and elsewhere. \r\n"

Contact: ChezOxendine@idonthaveit.com