Native American boarding schools in Kansas supported US land grab and forced cultural assimilation

A dozen Native American boarding schools in Kansas supported the federal government's mission of forced cultural assimilation as part of a tribal land grab, a new report states.

The boarding schools, including one in Topeka, were identified as part of a federal investigation to provide an in-depth accounting and reckoning of the harm done by boarding schools.

The report delves into the federal government's support of boarding schools, which were frequently operated by religious organizations that exploited child labor while stripping them of their cultural heritage.

"The report finds what Native Americans have known for generations — children at Indian boarding schools across America suffered beatings, abuse, forced labor and severe malnourishment for over 150 years as part of the American government's campaign to force their assimilation," said Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe.

The Department of the Interior and Bureau of Indian Affairs on Wednesday released a 106-page report and 488 pages of appendices on the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The documents are the first report of an ongoing investigation commissioned by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.

More: Review of Native boarding schools in Oklahoma, US expected to reveal thousands of deaths

Haaland is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe, making her the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary. She has said her grandparents were stolen from their families and forced into boarding schools.

"This report, as I see it, is only a first step to acknowledge the experiences of Federal Indian boarding school children," wrote Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, who is also a tribal leader in the Bay Mills Indian Community reservation.

Newland wrote that the report confirms the U.S. targeted indigenous children "in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession." It identifies 408 boarding schools operated or supported by the federal government "that were used as a means for these ends, along with at least 53 burial sites for children."

The 53 marked and unmarked burial site locations aren't being made public "to protect against well-documented grave-robbing, vandalism, and other disturbances to Indian burial sites," the report said.

More burial sites are anticipated to be found as the investigation continues, and death counts are expected to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.

Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, which formerly was a boarding school, has previously been identified as a child burial site. Its cemetery has more than 100 child graves. Gravestones there have been vandalized.

Kansas boarding schools were examples of harsh treatment

The report highlights a sampling of the conditions indigenous children faced amid American expansionism.

Haskell was cited in the report as an example of how assimilation efforts worked. There, children from 31 different tribes were intentionally mixed in order to disrupt tribal relations and pre-empt communication using native languages.

At the Kickapoo Boarding School in Horton, children frequently ran away. When they were captured, they faced corporal punishment.

"A prompt returning of the runaways and a whipping administered soundly and prayerfully, helps greatly toward bringing about the desired result," the report states, quoting from the department's 1899 annual report.

The 1896 annual report showed that the Horton school housed "three children to each bed." It was used as an example of what the department called well-documented "rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; disease; malnourishment; overcrowding; and lack of health care in Indian boarding schools."

Federal officials recognized the child labor was unsuitable for such young children.

While the Interior Department observed in the 1920s that many of the malnourished children were "much too young for heavy institutional labor," officials also acknowledged that child labor had "a very appreciable monetary value" that was "necessary" because of inadequate funding from Congress.

Haskell is again cited as an example, where children were "encouraged to enjoy the work" of cultivating strawberries.

The economic contributions of mandatory indigenous child labor remain unknown.

The report states that the United States established the boarding school system as part of a broader objective to take land from natives. Officials see the investigation as an opportunity to share past experiences and study current impacts.

"This reorientation of Federal policy is necessary to counteract nearly two centuries of Federal policies aimed at the destruction of Tribal languages and cultures," Newland wrote. "In turn, we can help begin a healing process."

Barnes, the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma chief, is among a group pushing Congress to establish a federal commission on Indian boarding schools. He and other Shawnee leaders have worked to preserve a boarding school where many Shawnee children were sent.

His tribe's history traces back to some Shawnee ancestors in Missouri and Ohio, who relocated to a Kansas reservation after treaties in 1825 and 1830. The U.S. government in 1854 cut the reservation's acreage by 90%, and the tribe relocated to Oklahoma amid conflict with settlers during and after the Civil War.

More: How can Kansas schools improve Native American education? Start by teaching it, advocates say.

12 Indian boarding schools identified in Kansas

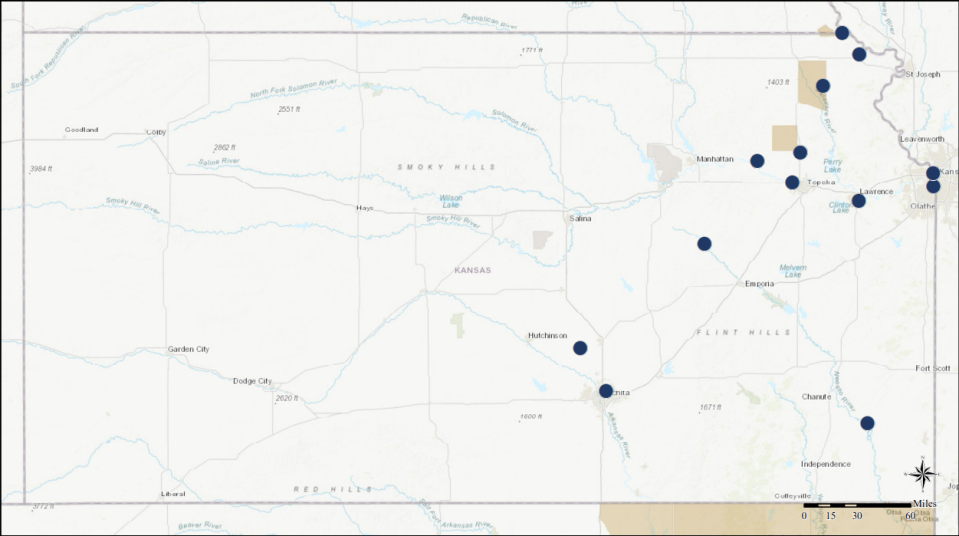

Federal investigators used historical records to identify 12 schools in Kansas with 14 school sites. Most had connections to Christian proselytizing.

• In Topeka, the Pottawatomie Mission Boarding School operated from 1848-73. The Baptists who established the school were allotted $50 for each child they boarded. The Southern Baptist Convention controlled the school at one point. Debt, inadequate funding and the removal of Pottawatomie tribes to Indian Territory led to its closure.

It was also known as the Potawatomi Baptist Manual Labor School, the Pottawatomie Training School and the Baptist Mission School.

• In Lawrence, Haskell Indian Industrial Training School was also known as Haskell Junior College, the Haskell Institute and its modern-day name Haskell Indian Nations University. It opened in 1884 and the last high school class graduated in 1965 before it transitioned to a junior college and later a university. It is a National Historic Landmark.

• In Hoyt, Pottawatomie Boarding School operated from as early as 1866 to as late as 1908. It was also known by the alternate spelling of Potawatomi. Historical records contended that "Indian parents cheerfully gave up their children."

• In St. Marys, the St. Mary Mission and School operated from 1847-1967, initially involving the Potawatomi. It was also known as St. Mary's College and Immaculate Conception Church. Jesuit archives indicated a dispute over whether $75 per pupil was enough to cover the costs.

• The Shawnee Methodist Indian Mission appears to have been the first indigenous boarding school in Kansas, opening in 1838 in Kansas City, Kan. A year later, it moved to Fairway, where it was known as Shawnee Methodist Mission and Indian Manual Labor School. It operated until 1862. The Methodist Episcopal Church, now the United Methodist Church, operated the school. It is on the register of historic places.

• Jesuit and Loretto missionaries established the Osage Manual Labor School for Boys and Osage School for Girls in 1847 in St. Paul. It was also known as Osage Catholic Mission and Schools, the St. Francis Institute, St. Ann's Academy and St. Paul. Records state the central focus of the school was manual labor, and they "adapted to service the needs of the incoming white settlers."

• The American Indian Institute operated in Wichita from 1915-39. It was also known as Roe Indian Institute. At one point, it had a Presbyterian Church affiliation.

• Halstead had two schools in the 1880s and 1890s. One was Halstead Mennonite Mission Boarding School, which was also known as Halstead Indian Industrial School and the Mennonite Orphan Home. The other was Halstead Seminary, also known as Halstead Fortbildungs-Schule.

• Highland had the Iowa and Sac and Fox Indian Mission School, which was also known as Iowa and Sac Mission, the Orphan Indian Institute, the Iowa, Sac, and Fox Presbyterian Mission and Highland Presbyterian Mission. It operated from 1846-68. It is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a Native American Heritage Museum State Historic Site.

• The Kickapoo Boarding School in Horton was affiliated with Presbyterian missionaries. It operated from 1871 to as late as 1931 and was also known as Kickapoo Industrial School, Kickapoo Training School and Kickapoo Rising Mission School.

• White Cloud had the Iowa and Sac and Fox of Missouri Boarding School from 1871 to as late as 1916. It was also known as Great Nemaha Boarding and Day School, Great Nemaha Industrial Orphan's Home and Great Nemaha Indian School.

• In Council Grove, the Kaw Methodist Mission School took on orphaned boys from 1851-54. The Methodist Episcopal Church operated the facility, also known as Kaw Manual Labor School, which is now on the register of historic places. After losing federal financial support in 1854, the school transitioned to serving white pupils as one of the first schools for white children in Kansas territory.

More: Kansas legislator apologizes after ‘tomahawk’ joke toward Native American colleague on House floor

Jason Tidd is a statehouse reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached by email at jtidd@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter @Jason_Tidd.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Report: Native American boarding schools in Kansas used child labor