Native American communities lashed by Covid, worsening chronic inequities

Amid the Covid-19 pandemic the president of one of the largest Native American– run non-profits has warned that health and economic disparities are still seriously affecting Indigenous communities, despite some progress achieved by the Biden administration.

Josh Arce, president of the Partnerships with Native Americans (PWNA), told the Guardian in an interview that challenges affecting Indigenous groups ranged from health inequities such as high rates of diabetes, heart disease and other illnesses to inadequate infrastructure such as running water and reliable electricity. Nearly all of these problems were worsened by the pandemic.

“The issues are, by and large, some of the same issues that we’ve been confronted with but they’ve been really highlighted and exacerbated by Covid-19 throughout the past two and a half years,” said Arce, who added that such challenges “really permeate all aspects of Native life and communities”.

For centuries, Indigenous communities in the US have faced challenges in public health, education, infrastructure and other areas, an aftershock of violent colonization and widespread racism.

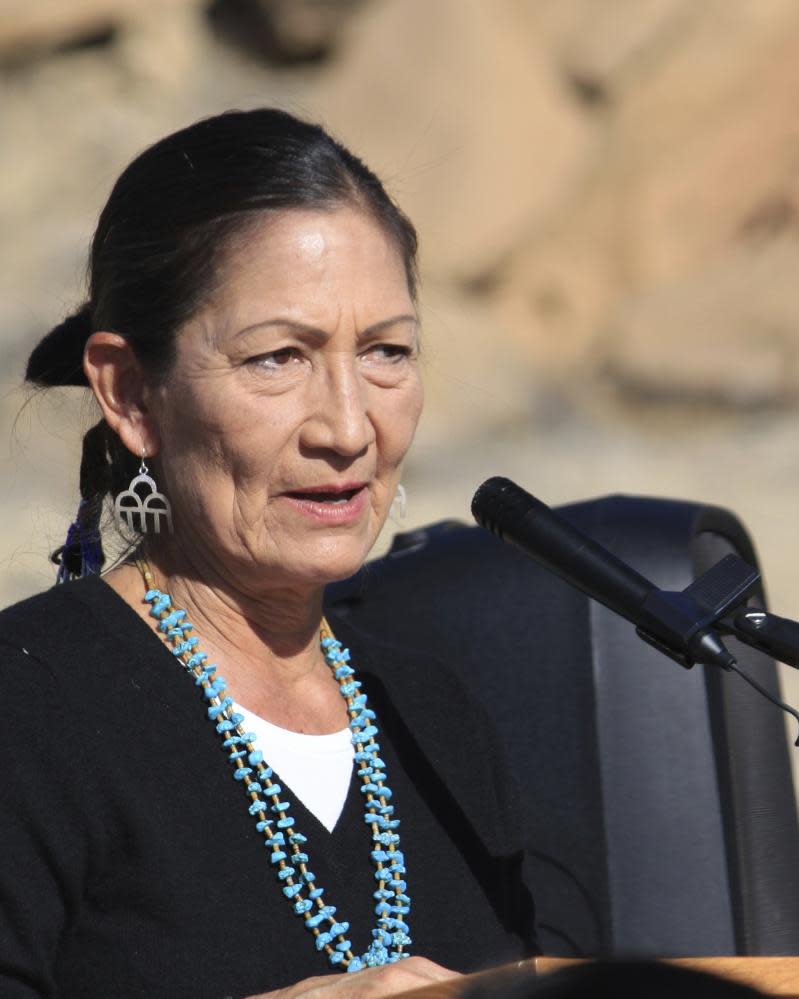

While the Biden administration has marked some progress, such as the appointment of Native American Deb Haaland as secretary of the Interior, an achievement that Arce noted was critical and brought hope to Native communities, Arce warned that more action is needed to ensure more progress for Indigenous communities in the US.

“The consultation and the meetings and the tribal input will only go so far until there starts to be some action behind the words that they’re saying and the policies that they want to put in place,” said Arce.

Like other marginalized communities, Native Americans were disproportionately affected by Covid-19, dying from the virus at twice the rate of white Americans. Health infrastructure in Native American communities, provided through the Indian Health Service, often is substandard , with hospitals and other medical centers generally under-resourced and understaffed, said Arce.

Native Americans are also more likely to be uninsured, according to data from the office of minority health in the US Department of Health and Human Services, adding another barrier to tackling complicated health challenges such as the current pandemic. “A tribal hospital system might only have six beds in their ICU, and so you start to run out of space a lot more rapidly than you do in a mainstream system,” said Arce.

The pandemic also affected mental health in many Indigenous communities. Native American populations already experience higher death rates from suicide, about 20% higher than non-Hispanic white Americans as of 2019, and higher rates of depression. But isolation and grief triggered by the pandemic has made the mental health epidemic worse, specifically among Native American youth, says Arce.

“That type of isolation, prolonged isolation, has really had an adverse effect on communities,” said Arce.

Arce also noted that generally poor mental health among Native American youth and insufficient resources to address mental health concerns were worsened by the pandemic, with rates of suicide among Native American teenagers “sky high”.

Economic challenges such as poverty – affecting one out of three Native Americans – and high rates of unemployment are also chronic concerns in Native American communities, said Arce.

While Arce noted that much-needed aid was delivered to Indigenous communities through the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan, different reservation communities, notably those in more rural areas, still face challenges securing basic infrastructure needs such as reliable electricity and running water.

“If we can overcome that next hurdle and really get these basic needs met for the reservation community, that’s going to be a huge improvement to the lives and wellbeing for those tribal members,” said Arce.

Education nationwide has also been hurt by the Covid-19 pandemic, but historically underfunded schools within the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) system were already struggling to cope. The impact of the pandemic – such as meeting remote learning needs – has made the sector even more challenging.

Native communities had problems accessing reliable, high speed internet, an inequity termed the “digital divide”. Previous attempts to deliver broadband to tribal communities did not take into account power limitations in some areas. While there has been a surge of funding from recently passed social aid packages, Arce says that communities are still facing long-term problems such as the blighted conditions of school buildings, understaffed districts and teachers not receiving adequate pay.

Climate change will also affect Indigenous communities, Arce said, with its effects differing by region. For low-lying tribes based in states like Florida or Louisiana, predicted sea level rises could subsume communities. Similarly, Indigenous people in the northern plains could see their growth seasons, a critical fixture, disrupted.

“They’re going to essentially get evicted by the results of climate change,” said Arce.

Arce said that the Navajo nationis still dealing with the aftereffect of pollutants from uranium mining that occurred decades ago. Other tribes have struggled without basic necessities like clean drinking water, with one in 10 Indigenous Americans lacking access to safe tap water or basic sanitation, a phenomenon called “plumbing poverty”.

Arce said that many of these struggles within Native communities aren’t new phenomena but areproblems that have been plaguing residents for decades.

While the Biden administration is “definitely [moving in] a positive trajectory”, Arce said he is hopeful that more action can be taken in combination with recently passed policy to address basic necessities in tribal communities and other overwhelming needs.

“I know that the pace of government can be very slow so I hope that these policies and improvements turn into action and not just be a policy that doesn’t have a whole lot of teeth,” said Arce.