Nato has an enemy within, and he’s heading for a fall

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Turks go to the polls at the weekend, they will not only be determining the future course of their country’s political development. They will be deciding whether Ankara can maintain its position as a vital pivot of the Western alliance.

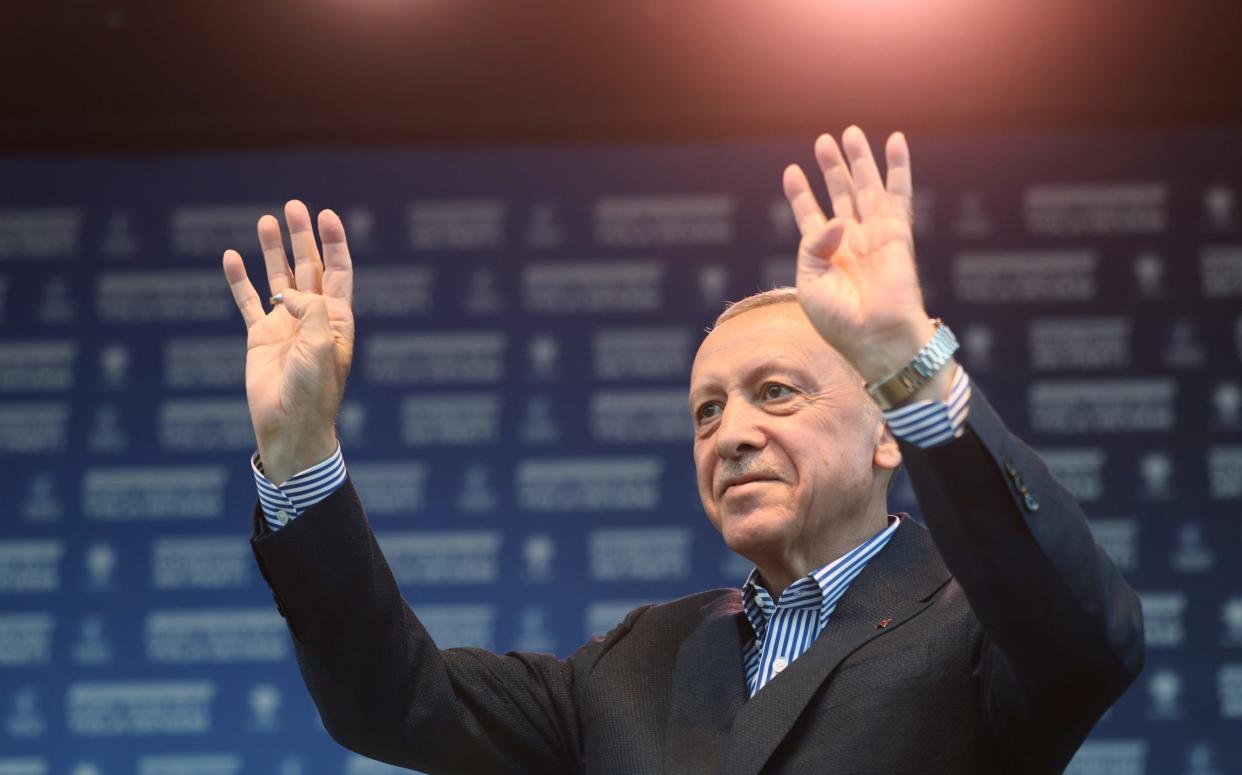

With the Turkish economy in meltdown and the country still struggling to come to terms with February’s devastating earthquake, opposition parties believe they have a rare opportunity to oust Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the country’s authoritarian leader.

Once hailed as a pro-business moderniser who would forge closer ties with Europe – including Turkey joining the EU – the 69-year-old Turkish president’s two decades in power have seen him adopt an increasingly autocratic approach to governing his country’s affairs, one that has acquired a distinctly Islamist outlook.

This has led to questions being raised among Western leaders about Turkey’s continued reliability as a Nato ally.

Tensions first emerged over Ankara’s support for al-Qaeda-linked Islamist groups during the Syrian civil war, and intensified when Erdoğan was blamed for causing the mass migration of Syrian refugees into southern Europe.

These were compounded when Turkey signed an arms deal in 2017 with Moscow to buy Russia’s state-of-the-art S-400 anti-aircraft missile system, which was specifically designed to shoot down Nato warplanes. The US responded by excluding Ankara from the F-35 stealth fighter programme and imposing sanctions. More recently, Turkey has frustrated Nato leaders with its spurious objections to Sweden joining the alliance.

It is arguably only by dint of Turkey’s strategically vital location on Nato’s south-eastern flank that it has managed to retain its membership. Consequently, many Nato leaders will be desperately hoping, along with tens of millions of Turks, that Sunday’s presidential and parliamentary elections will result in Erdoğan being ejected from power.

The ballot is certainly one of the closest contests Turkey has witnessed in recent years, with the latest polls indicating that opposition leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who is backed by a six-party alliance, enjoys a slight advantage over Erdoğan. Support for Kılıçdaroğlu, a 74-year-old former accountant who heads the Republican People’s party, has been building steadily over his commitment to dismantling the oppressive authoritarian system established by Erdoğan as he and his allies in the Justice and Development Party (AKP) have set about destroying the secularist constitutional framework established by Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s pledge to scrap Erdoğan’s presidential system by re-establishing the powers of parliament and the office of prime minister, as well as guaranteeing the independence of the judiciary and the press, have particularly struck a chord with young Turks. Many of them yearn for relief from Turkey’s parlous economic plight – inflation is currently running at around 45 per cent – and state-sponsored repression.

As Kılıçdaroğlu remarked in a recent BBC interview: “The youth want democracy, they don’t want the police to come to their doors early in the morning just because they tweeted. I am telling young people they can criticise me freely. I will make sure they have this right.”

Beyond Turkey, Western leaders have taken a keen interest in Kılıçdaroğlu’s commitment to reaffirming his country’s Nato credentials, pledging to repair relations with the US. There has even been talk of resurrecting Ankara’s long-dormant bid to join the EU.

While Kılıçdaroğlu’s bid for power represents one of the most serious challenges Erdoğan has faced since he first steered the AKP to victory in 2002, Turkey’s president nevertheless remains a formidable opponent. This, after all, is a man who, during his early political career in the 1990s, was willing to serve time in a Turkish jail for espousing his Islamist views.

Having helped the AKP to achieve multiple election victories, Erdoğan enjoys a number of advantages over his rivals, not least the enormous powers he enjoys within the all-powerful presidential system he established after the 2017 constitutional referendum. This has resulted in the closure of most anti-government media outlets and the nationwide persecution of citizens said to be involved in the 2016 coup attempt against Erdoğan, which resulted in the dismissal of tens of thousands of police, military personnel, civil servants and judges, with more than 95,000 people being detained.

Erdoğan has also shown himself to be a bad loser when results go against him. When a political rival won the election for the mayorship of Istanbul from the AKP in 2019, Erdoğan claimed the result was fixed and ordered a rerun. And even though, on that occasion, he ultimately accepted the result, there are concerns he will not be so gracious if Sunday’s vote does not go his way. Turkey’s interior minister has already laid the ground for challenging the outcome by claiming the opposition is part of a Western “political coup attempt”. It suggests that, even if the opposition wins, there is no guarantee we will have seen the back of Erdoğan.