Nature gap: Black people strive to overcome history of recreational barriers, reconnect with Florida land

Brandon Thompson grew up wanting to be a cowboy, complete with rugged boots and a big hat, roping bulls and riding a horse off into a fiery Florida sunset.

He saw himself hunting and fishing, a free spirit answering the call of the land and water.

“I used to go to rodeos when I was really young, in elementary school. I’d even wear a cowboy hat. That’s what sparked my flame and fire for the outdoors,” the 33-year-old said, taking a break between clients at his barbershop, Eazy Livin’ Studios in New Smyrna.

But Thompson’s dream of life in the great outdoors, maybe even joining the rodeo, flickered away. His mother focused on raising her family in the town of New Smyrna Beach. And the occasional fishing trip with his father in West Palm Beach gave way to the sweat and grind of football and track in high school.

Breaking stigmas and sterotypes: Florida women hope to 'diversify the lineup' for Black surfers

Things like heading off into the Florida woods to camp seemed out of the question for a Black teen like him, he said.

“You’d hear things like you couldn’t fish if it wasn’t on the river. And you couldn’t just go hunting if you didn’t own land. There are fears because you didn’t know if someone was out there who’d want to hurt you,” Thompson said.

“And when you grow up without somebody to show you or take you places, then you don’t have the motivation. I didn’t have anyone to really show me.”

But when Thompson was in his 20s, with a short stint in the Army behind him, that changed. He was ready to revisit a childhood dream. “I just felt I should be able to be myself,” he said.

Now, draped in camouflage, carrying a .20 gauge shotgun, Thompson wades through the thick mud and muck on Merritt Island hunting for ducks. He hopes to connect others, including Black youth, back to the land.

Thompson is one of many trying to encourage others who look like him to explore the nation’s parks and green spaces. It’s a move to break through the legacy left behind from Jim Crow-era rules, segregationist attitudes, and economic barriers that kept many Black people away from Florida’s most sought-after outdoor spaces.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, laws and social traditions were set in place by white leaders to bar Black people from certain choice green spaces, including beaches, recreational areas and parks.

That coupled with lynchings, massacres in towns like Rosewood and so-called “sundown” customs kept Black people from traveling overnight in certain cities or venturing into unfriendly territory to hunt or fish. The experiences left many Black people with the bitter understanding that much of Florida’s wild could be dangerous for them. Not because of what might be in the water or foraging in the scrub, but because of racism.

Home on the range: Black gun owners take aim at training, education with formation of Brevard gun club

'Bridging the gap': New generation of Black leaders in Brevard making marks on politics, advocacy

Nearly 60 years after the passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act cleared the way for equal access to public parks and beaches, the journey to full equality in the nation’s recreational spaces is improving but remains incomplete.

“Historical legacies don’t go away too easily, neither do cultural patterns, but the efforts are being made,” said William E. O’Brien, author of Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South and an associate professor of environmental studies at Florida Atlantic University.

“If someone is telling you that you don’t belong here, then that has an impact,” he said.

Diversity gap

The number of Black visitors to national parks proves that point. A National Parks Service survey issued in 2018 – before the COVID pandemic – shows that Black people, about 13 percent of the U.S. population, made up just 6 percent of visitors to its 423 locations nationwide. There are no statistics available to show how many people of color were among the 29 million visitors to Florida’s 174 state parks in 2019.

The National Parks System oversees sites such as the Grand Canyon, the 2,100-mile-long Appalachian Trail, and the monuments in Washington, D.C., as well as locations like the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta, established in 1980, which houses the civil rights leader’s childhood home.

Not only are Black people not visiting the parks like their white counterparts; they aren’t represented among the staff in equitable numbers either. Only about 7 percent of the agency’s workforce is made up of African-Americans, the park service reported.

“We know that parks have not always been welcoming to people of color,” Kristine Stratton, president of the National Recreation and Park Association, wrote in a statement responding to an incident involving a Black bird-watcher being harassed while nature walking in New York City’s Central Park.

Among the NRPA’s recommendations; hire a more diverse staff and feature inclusive marketing plans. The federal Civil Rights Commemorative Initiative has worked on incorporating more stories from the Black and Indigenous experience into park exhibits.

Leaping great boundaries: Superman's son comes out as bisexual, draws praise and criticism

Rosa Lee Jones: Civil rights pioneer, educator to be honored with mural in Cocoa

The diversity gap in recreation also has captured the attention of business leaders. In 2019, the CEOs of more than 50 outdoor-related companies pledged to diversify hiring and marketing.

The National Health Foundation, a private health research group, dubs the disconnect a “diversity gap in the outdoors.”

Bridging that gap takes time, and requires overcoming deep cultural and historical memories, O'Brien said.

Life, culture and recreation

To be sure, Black communities across Florida created their own safe, green spaces from clearings in the woods to church lots and backyards. People grew gardens, held cookouts beneath palm trees, and fried freshly caught fish by the riverside or in canals for the Fourth of July.

“We had everything within the community with the facilities that we had,” said 75-year-old community activist Joe McNeil of Melbourne.

“No one had to warn us about where not to go. It was set in stone that we couldn’t go. We’d stay in our areas where we’d feel safe. If we went into the woods, it was in places that were adjoining where we were,” McNeil said.

As the state emerged from the aftermath of the Civil War, a wave of new rules relegating Black people to second-class status was birthed out of an 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding segregation. The ruling provided the backbone to a systemic wave of laws barring Black people from having access even as federal and state parks were created to preserve the nation’s crown jewels of scenic lands.

The irony: some of those spaces, like Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, were seized from Indigenous people and guarded early on with help of Buffalo soldiers, the all-Black troops of the 24th Infantry, and the 9th Cavalry.

The trend also saw parallels in Florida as officials attempted to capitalize on visitors coming to escape northern winters with the creation of protected public spaces. So-called “Negro beaches and parks” also were created, but in far fewer numbers and typically out of the way for many Black residents, who also had to worry about traveling the highways, O'Brien said.

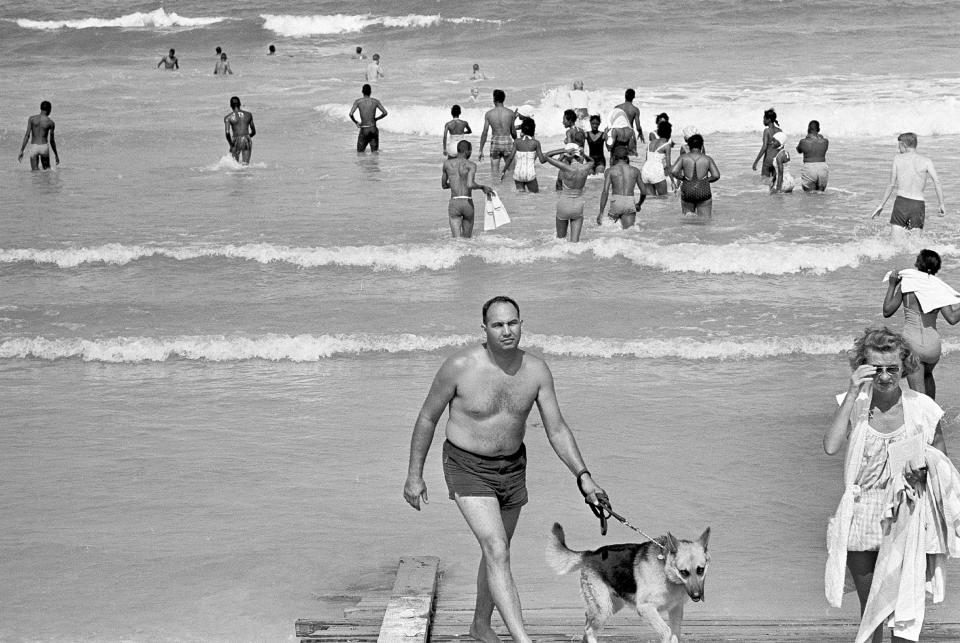

Battle of the beaches

During the height of the civil rights movement, the state’s beaches – stretching over 800 miles – would prove to be a battleground for breaking down the barriers of recreational discrimination.

Pensacola Beach on Santa Rosa Island is known for its gin-clear waters and sugar-white sand beaches along the Gulf of Mexico. It became a popular tourist destination, but not for Black people.

By the early 1950s, Black residents – whether young veterans who fought in World War II, teachers, doctors, or others – across Florida began to resist. They weren’t allowed in Pensacola Beach. Instead, they had to pack water, chicken and bread since Black people could not enter or be served by white establishments, and trek 18 miles to get to the largely undeveloped Perdido Key.

The facilities on Perdido were severely lacking, residents recalled. One Black resident named Willie Brown, writing in a letter to the editor, likened the facilities at Johnson Beach to a “dilapidated barn on piers that actually resembles a hut on stilts in the Belgian Congo.”

Brown said it had one sink, one toilet, no telephone, no lifeguards.

“Won’t somebody do something about this ‘death den?’ ” Brown wrote.

The beach was soon named Rosamond Johnson Beach after a Black U.S. Army Private, the first person from Escambia County killed in the Korean War. It would become the only option for Black residents in northwest Florida.

Bringing light to darkness

In south Sarasota County, Venice Beach was the appointed beach for Black residents according to historical documents and sources.

But it was about 25 miles away from Newtown, Sarasota’s historically Black neighborhood in north Sarasota County.

To even travel to the beach was fraught with obstacles, from a lack of good roads or transportation. The irony was that the nearest beach was 6 miles from Newtown but both Lido Beach and Siesta Key Beach were designated “white only.”

The beach desegregation movement in Sarasota County began in 1951 with Mary Emma Jones, who owned a barbecue restaurant and taxi stand. Jones requested the Manatee County Commission integrate beaches in Sarasota.

Instead, in 1955 commissioners offered to build a pool in Newtown for its Black residents.

Unsatisfied with the commission’s efforts, Jones and others began organizing caravans in September 1955 to go from Newtown to Lido Beach for “wade-ins” to assert their legal right to visit local beaches.

Fredd Atkins, 74, said that during his youth, many of the children swam in freshwater swimming holes around Newtown. But Atkins said visiting the beach was something he’d always looked forward to.

Atkins was about 7 years old when the “wade-ins” began at Lido.

Sarasota racial history: From a secret history to a tourist attraction

Presidential Medal of Freedom: Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore posthumously nominated

“It was always an amazing experience for us to go to the beach, to get in the saltwater because we swam in the swimming holes ... but it was a struggle. We never felt welcome at Lido, at Siesta Key. So even when we went it was by force of will,” Atkins said. “Even to this day so few Black people go to Lido beach, it’s still basically segregated.”

Even Daytona Beach, known to many as the World’s Most Famous Beach, was off-limits to Black people until the late 1960s. Mary McLeod Bethune, the founder of the small Daytona Beach school for Black girls that grew into Bethune-Cookman University, recruited local leaders to secure a 2 1/2-mile strip of oceanfront south of New Smyrna Beach for Black people.

The spot is now a historic site.

Harold Lucas said the freedom Black people have now to go to any beach they want in or near Daytona Beach only came about gradually. The 89-year-old said some Black people tried to start swimming and sunbathing at the city’s beach in the late 1950s, but that usually didn’t end well.

“They’d still point you to Bethune Beach,” said Lucas, who grew up in Daytona Beach’s Midtown and still lives there. “People would pass by in their trucks and say ‘you need to leave.’ ”

‘Save the manatees’: Decades-old debate about manatees’ future in Florida rages on as sea cows starve

Face to face

In 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. visited the Sunshine State, but far from relaxing, he arrived to help recruit youth from across Orange, Volusia and Brevard counties to protest.

It was less than a year after President John F. Kennedy, who supported new legislation to address civil rights, was assassinated in Dallas.

King and the Sunshine State: Five fascinating connections Martin Luther King Jr. had to Florida and the Space Coast

First Black woman to join ISS expedition: NASA assigns Jessica Watkins to SpaceX Crew-4

That spring and summer, King and other civil rights leaders intensified efforts to support the passage of landmark federal legislation, stalled in Congress, that would put an end to desegregation in hotels, movie theaters, and recreational areas.

A flashpoint that summer became the coastal tourist city of St. Augustine, with its sun-splashed postcard image. The city – which kept its old slave market where men, women, and children were sold off as property as a centerpiece of tourism – was set to celebrate its 400th anniversary with federal funding in 1965. Black people were excluded from the decision-making.

“We are determined this city will not celebrate its quadricentennial as a segregated city,” King said about the campaign in St. Augustine, according to a New York Times article documenting his visit.

“There will be no turning back,” he said.

The city’s bustling beaches remained segregated and certain businesses off-limits to Black people. And the nation was watching.

“It was the roughest area at that point in Florida. St. Augustine was our Selma, it was rotten and full of Klan members. It was just the culture of the times,” said Rosemary McGill, a Satellite Beach resident who marched with Dr. King in St. Augustine that long hot summer.

'Trouble don't last always': Activist remembers King, St. Augustine's civil rights struggle

St. Augustine history: Civil rights activism roots run deep

McGill, who attended the March on Washington the year before, was one of seven students from Brevard recruited by Brevard’s NAACP president W.O. Wells of Greater St. Paul Missionary Church in Cocoa. “We came face to face with the Klan. But we marched,” she said.

King hoped a series of marches would draw attention to long-festering tensions in the city. They did. There were marches, sit-ins, and a push to desegregate the beaches. There were also death threats from opponents. Gunmen fired at the home King was staying in. A white motel owner was photographed pouring acid into a pool with protesters.

A big clash came on June 20, 1964, when the segregationists confronted activists, including many from the historically Black Florida A&M University, as they waded in the surf along the beach. Florida state police in full uniform dashed into the water as segregationists fought the activists amid the waves.

“The saddest thing is that it was the same sand, the same beach,” McGill said.

“I marched in St. Augustine but I didn’t participate in the ‘wade-ins.’ But imagine this, it was the same ocean, the same beach and it was segregated. But we didn’t fight to desegregate because wanted to eat their food or go where they went. We had our own culture. We could care less about their food, their parks. No, what we were doing was about right to be there,” she said.

By July, the legal fever of segregation broke. The Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Johnson, bringing an end to the policies that kept restaurants, businesses, and recreational spots segregated.

Up and away: Young Brevard minorities complete aviation STEM course

No limits

Somewhere along the muddy trails burrowed deep in the brush of Canaveral Groves, Marquee Cloud has hit his stride. His immediate thoughts are not on history but what the day will bring.

Straddling a four-wheel all-terrain race quad, he describes the joy of rediscovering Florida’s wildlands through the extreme outdoor recreation sport of mudding. He speeds past alligators, wild pigs, and other wildlife along the water’s edge. If the moment had a soundtrack, it would be the song “Benjamins” by trap music star Future.

“I’m in the matrix every day, I'm paying close attention

My situation every day, I’m pushing to the limits ...”

“I love it,” the 35-year-old Rockledge resident said. He also acknowledges that what he is doing would be something unimaginable for some in the Black community even two generations ago. And he is mindful of the sacrifices that came before with the civil rights movement, said Cloud, whose all-terrain vehicle costs between $12,000 to $18,000.

“It’s the greatest feeling riding the trails because you feel so free, you feel unstoppable. I can drive in small lakes, dry trails. You get dirty and see your bike get through that big nasty mud, it’s all just impressive,” he said, easily slipping into the role of a mudding ambassador.

For him, there are no limitations when it comes to using the state’s recreation spaces. But mudding is a definite shift from the warnings instilled in him as a child when it came to recreation. His experience is also an example of how thoughts and culture are advancing and breaking boundaries once imposed on the Black community.

But there are misgivings. Often Cloud finds himself one of fewer than a handful of Black people venturing out in the woods of the Grove. He’s also seen amid the greenery, the occasional Confederate flag – a symbol of the failed Southern Confederacy – along with some cold stares.

Cloud is unmoved.

“Yea, people still tell me that they wouldn’t be out here. But I watch my surroundings. If I see someone I don’t know I keep going,” Cloud said, acknowledging that at one point growing up, he would never have considered jaunting through woods. But seven years ago, tired of watching the weekends pass by, he took up an invitation from his white friends in Sebastian.

“You really have to trust people. ... Even to this day, when I’m out mudding or partying, I’m always watching.”

Cloud says he wants to see more of his generation get outdoors.

“You see some who just stay close to home, who go to the club, smoke. But we have to break that cycle. My son is 2 years old. I bought him a little electric all-terrain vehicle,” Cloud says with a laugh. “I getting him used to it,” he says of his son, King.

“I feel like I’m moving some to this path ... We don’t want this to be a generational thing. We need to be more open, it’s time to embrace different things,” he said.

Thompson agrees.

For him, the epiphany came when he was 23 years old and struggling. Thompson was sitting alone at night in one of Ocala’s roughest neighborhoods. And like a call to prayer lilting into the evening air, he heard an announcer’s voice blaring from speakers at a livestock pavilion. It was an event showcasing, of all things, a rodeo.

“I saw that this street life was nothing,” Thompson recalled.

He moved back home to New Smyrna, went to barber school, and bought a compound hunting bow. He decided to learn about recreational hunting.

That doesn’t mean it’s always easy, Thompson said, recalling a hunting trip with fellow Black hunters, members of a predominantly Black hunting club 24/7 Hunt.

“When some people see us at the ramp, five or six Black men in our 30s, with trucks, the boats, and wearing our hunting gear, their mouths drop. You sense it,” the first-generation hunting advocate said. “We get it all.”

But the club members have a comradery, cracking jokes as they boat out to their hunting sites or while seasoning and cooking up the fish or ducks they caught. “Those boys are like my brothers,” he said. “They took me under their wing.”

Before the pandemic, Thompson had co-founded a program called No Boundaries that helped inner-city youth to experience horseback riding.

“Just get them out there, get a fishing pole, just take action and get out there. Find somebody, pick their brain. I’m still very, very new to the outdoors but when the opportunity presented itself that’s what I did,” Thompson said.

Both Cloud and Thompson also are active on TikTok, sharing videos of them in the wild, partly in the hope that it inspires others.

Reclaiming recreation

Activists continue to highlight the need for rethinking the use and development of green spaces for recreation in inner cities.

Several organizations have stepped up to educate youth on recreation, such as Soul Trak Outdoors, a D.C.-based nonprofit promoting outdoor spaces for minorities and providing training for youth in areas like gardening, hiking, and other recreational activities.

In Florida, private groups like Outdoor Afro – with a mission of reconnecting Black people with green spaces through hiking, kayaking, birding, biking, or other activities – typically have meet-ups in Orlando and St. Petersburg.

There is Camille Hadley, community activist and greenspace advocate, who moved to the Powell-Driskoll subdivision of Palm Bay in Brevard County and saw a need to reimagine the way parks and other spaces were used.

Municipalities are also involved, although COVID has created some limitations. In Pensacola, youth can sign up to learn angling, archery, and fishing. In Palm Bay, there are ranger-guided tours of Turkey Creek.

Sharing knowledge: South Melbourne teens attend free wealth-building camp

'Sky is limit': Brevard County pilot teaching youth to fly

Thompson said it’s important to take that first step.

“Whatever you do, get out, walk nature trails. We are so disconnected from the real world,” he said, pointing out that the barriers that faced his grandfather’s generation are no longer in place.

“If you get outside, you find yourself.”

Reporters Samantha Gholar Weires of the Herald Tribune, Eileen Zaffiro-Kean of the Daytona Beach News-Journal and Jim Little of the Pensacola News Journal contributed to this story. J.D. Gallop is a Criminal Justice/Breaking News Reporter at FLORIDA TODAY. Contact Gallop at 321-917-4641 or jgallop@floridatoday.com. Twitter: @JDGallop.

This article originally appeared on Florida Today: Black people seek to reconnect with Florida land after Jim Crow legacy