Navy Looking To Operate Air Combat Drones From Wide Range Of Ships

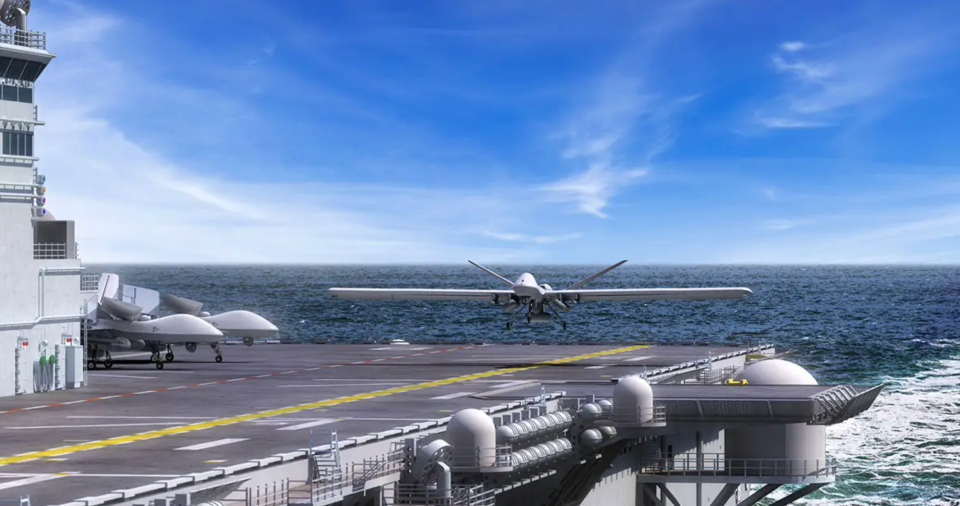

Considering that the U.S. Navy’s future carrier air wings are planned to feature up to 60 percent pilotless aircraft in the coming decade, we know remarkably little about the service’s efforts to develop advanced aerial drones. But a new document provides some interesting insight into these evolving plans, namely the vision of fielding a “high volume of low-cost aircraft” that can be launched from ships other than carriers.

While details are scarce at this point, these drones may well include Navy equivalents to the Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft, or CCAs — future advanced drones with high degrees of autonomy designed to operate collaboratively with crewed platforms.

A Request for Information (RFI) was released yesterday on behalf of the Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division and the Office of Naval Research (ONR) under the title Sources Sought for Common Aircraft Launch and Recovery Technologies for Group 3-5 Attritable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs).

The document calls for information on “revolutionary” common Aircraft Launch and Recovery Equipment (ALRE), suitable for drones that are “expected to be fixed-wing, low-cost, and reusable/attritable, and would operate off of non-carrier vessel (CV) sea-based platforms.”

The “low-cost” and “attritable” aspects are interesting in themselves. Broadly speaking, “attritable” implies a drone inexpensive enough for commanders to be willing to lose it on high-risk missions. In other words, the threshold for an acceptable loss is much lower compared to far more costly 'exquisite' systems.

More recently, within the Air Force, for at least some of its CCA drones, the term has been somewhat superseded in favor of “affordable mass,” which implies UAVs that are available in large enough numbers to act as force multipliers, something The War Zone previously highlighted was already happening back in 2021. Regardless, as far as the Navy is concerned having a lower price point means that more drones can be procured, while “attritable” indicates that a degree of losses will be deemed acceptable, at least in certain scenarios.

As far as the UAV categories in the RFI are concerned, these cover a fairly broad range of pilotless aircraft. Group 3, for example, includes drones weighing between 55 and 1,320 pounds, normally operating below 18,000 feet at speeds less than 250 knots. A typical example is the RQ-7 Shadow. Group 4 comprises drones weighing more than 1,320 pounds and normally operating below 18,000 feet, at any speed, such as the MQ-8 Fire Scout or MQ-1 Predator. Finally, Group 5 drones also weigh more than 1,320 pounds but typically operate higher than 18,000 feet, at any speed, and include the MQ-9 Reaper all the way up to the much larger RQ-4 Global Hawk. More specifically, the RFI calls for information relating to the launch and recovery of drones weighing between approximately 1,000 and 10,000 pounds, implying that only the very upper end of Group 3 is included. This is also where the 'sweet spot' appears to be for many CCA concepts.

While the RFI specifically excludes rotary-wing drones, there is otherwise no mention of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) capabilities, which would appear to open up the option of much less complex ALRE requirements. Certainly, the launch and recovery aspects as outlined in the RFI appear to be deliberately vague, although it’s not clear if fixed-wing VTOL drones would be considered among the possible launch/recovery solutions. As well as hybrid fixed-wing VTOL drones like those from Volansi, the Navy has previously explored tail-sitting VTOL drones, like the TERN (Tactically Exploited Reconnaissance Node), that was being developed for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Office of Naval Research.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qGoKR-xUa4s

According to the document, the kinds of ALRE technologies that the RFI seeks to explore “shall allow the Navy to deploy a high volume of low-cost aircraft to supplement the Air Wing of the Future (AWOTF), promote critical asset survivability, and improve distribution of Naval airpower.”

“Information is sought for concepts that minimize space required on the deck and maximize the number of compatible low-cost/attritable UAVs,” the RFI continues. “Concepts may utilize modularity or a family of systems to support variable aircraft weights and launch/capture velocities.”

The latest RFI is notable in that it envisages these future drones operating from a fairly wide range of ships.

The RFI lists what it describes as “potentially relevant Air Capable Ships (ACS),” comprising expeditionary sea base (ESB), destroyer (DDG), amphibious transport dock/landing platform dock (LPD), or an unspecified “new ship class.” Common requirements for these vessels are flight deck sizes of approximately 50-200 feet long and 40-100 feet wide.

Furthermore, potential ALRE designs could be portable or permanently installed for use on a single ship class or multiple ship classes.

The Navy already has experience operating drones from ships other than aircraft carriers. Notably, back in the 1980s, the Iowa class battleships were adapted to launch and recover RQ-2 Pioneer drones, which provided over-the-horizon targeting and reconnaissance, including in Operation Desert Storm. The drones operated out to a range of 110 miles from the battleship surface group and had an endurance of eight hours.

More recent examples of different drones that have operated from Navy warships include the RQ-21 Blackjack, the ScanEagle, and Aerosonde. However, these are much smaller UAVs than those outlined in the RFI, weighing approximately 135 pounds, up to 48.5 pounds, and up to 32 pounds, respectively.

Interestingly, the RFI doesn’t rule out potential concepts for ALRE that would involve “sea-based platforms other than ships.” Candidates could include various kinds of uncrewed platforms, for example. The U.S. Marine Corps has previously looked at floating bases as part of its Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept, which could also lend itself to supporting drone operations.

While the Concepts of Operations (CONOPS) for these kinds of drone operations are still taking shape, the RFI does stress that the ALRE should be optimized to generate the maximum sortie rates, meaning that a large number of UAVs can be launched and recovered in a short amount of time. To help achieve this, the RFI suggests that consideration be given to the “facilitation of UAV handling (preferably, automated) and storage pre and post-launch and recovery.”

“Novel approaches for flight control techniques, innovative coupling of ship/aircraft aerodynamic effects [and] ship/aircraft communications” are all other aspects that potential respondents to the RFI might also want to address.

The process of launching and recovering a non-VTOL drone, especially one weighing up to 10,000 pounds, from a vessel other than a carrier or big-deck amphibious assault ship already brings a number of challenges.

Key among these are the space restraints when operating without the benefits of a large flight deck. Depending on the chosen methods for the ALRE, there are also the problems of generating enough energy for launch and then absorbing energy imparted during recovery. These concerns, in turn, will have a major effect on the launch/recovery envelope, sortie rates, and controllability of the drone during these portions of the mission. There are also various requirements in terms of the interface between the ALRE/drone and the host ship, including power, hydraulics, cooling, communications, and more.

On the other hand, the Navy does already regularly launch (but not recover) target drones from ships other than carriers. The kinds of zero-length launchers used for these kinds of operations could illustrate one path toward solving the drone-launch challenge.

Noteworthy, too, is the fact that the U.K. Royal Navy has also taken target drones as a starting point for developmental work on its future ship-based UAVs, although these have, so far, also focused on operations from aircraft carriers.

https://www.twitter.com/chrisjwoods/status/1443225836212133891?s=20

Another extant drone that features runway independence as a core feature is the XQ-58A Valkyrie. This UAV does not require a runway of any kind in order to get airborne or land at the end of a sortie, launching via rocket boosters from a stand and being recovered via a parachute and airbags. Its attributes, which it shares with the UTAP-22 and Air Wolf lower-end collaborative teaming drones, also manufactured by Kratos, could also be of interest to the Navy for certain shipborne applications. There is even a containerized launch concept for the XQ-58 that could lend itself particularly well to modular installation on ships. Once could see how these types of drones that can fight alongside manned aircraft could be launched, recovered, refurbished and launched again from a surface vessel.

An RFI, by its nature, raises more questions than answers, but this document does at least indicate some of the ways the Navy is looking at expanding its future drone operations. While potential drone missions are conspicuously absent from the RFI, they could potentially cover a very wide range of applications.

Responses to the RFI are needed by October 26, 2023.

Although the Navy’s uncrewed aircraft plans are lower profile than those of the Air Force, we already know that the service wants the majority of the aircraft in its future carrier air wings to be pilotless. At least some of those same drones will also be expected to offer interoperability with the Air Force, with each service using its own crewed aircraft to control each other’s CCAs, an idea we have explored in the past.

Carrier strike groups, as well as potentially other naval assets, being able to readily take control of Air Force drones during operations in certain circumstances, and vice versa, could be extremely useful. For example, there would also be the option of ship-launched Navy CCAs being ‘handed over’ to Air Force B-21 stealth bombers, or other long-range platforms, as required.

Earlier this year, Rear Adm. Andrew “Bucket” Loiselle provided some details about the Navy’s drone plans, as well as how those uncrewed aircraft would be expected to operate alongside its own sixth-generation crewed stealth combat jets. These efforts are a part of the Navy’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program which you can learn about here. While distinct from the Air Force’s NGAD initiative, there will be a lot of overlap.

“As we looked upon that air wing of the future, we have numerous unmanned systems,” Loiselle said, back in April. “You’ve heard talk about CCAs [and] MQ-25.”

The MQ-25 Stingray is an uncrewed tanker aircraft with a secondary intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability.

“We’re developing an unmanned control station that’s already installed on three aircraft carriers, and that will be the control station for any UAS [uncrewed aerial systems] that we buy,” Rear Adm. Loiselle added. “[There is] unbelievable cooperation with the Air Force right now in the development of mission systems for both sixth-gen [combat jets] and CCAs…”

The drone control system referred to by Rear Adm. Loiselle is the MD-5 Unmanned Carrier Aviation Mission Control System (UMCS), used aboard Navy carriers in conjunction with the new Unmanned Aviation Warfare Center (UAWC).

The RFI raises the possibility of future CCAs — among other drones — being launched and recovered from a wide range of vessels, not just carriers, with some of these operations controlled by the Navy’s future sixth-generation crewed combat jet, also referred to as F/A-XX, acting as a ‘quarterback’ for drones.

Having Navy CCAs, or any other kinds of drones, for that matter, flying from different warships also resonates with broader goals of being able to operate over much wider areas, and generate more of the much-needed ‘combat mass,’ something that is seen as being of particular importance for future campaigns in the Pacific theater. Simply put, distributing these kinds of pilotless aircraft across multiple vessels not only increases their survivability and boosts the overall effectiveness of those vessels, but could also help address the issue of operating at “significantly longer ranges than we have contemplated before,” as Rear Adm. Loiselle put it.

“The type of platform that delivers […] ordnance is less important than the ability to do so,” Rear Adm. Loiselle continued. Here again, having an armed CCA, or another kind of drone that can operate from a destroyer or landing platform dock, for example, would mean that those ordnance-delivering capabilities are not restricted to the carrier strike group in the same way that they are today.

While aircraft carriers remain a highly flexible and survivable way of bringing air power to bear where it’s needed, they are also prime targets for hostile actors. In the Pacific context, carriers would be at the very top of China’s list of targets, while the limited number of well-established fixed bases on land are ever more vulnerable to existing and emerging enemy long-range strike capabilities. With that in mind, anything that can increase the survivability of the Navy’s future air power assets will likely be of great interest.

Also, by distributing tactical airpower across vessels operating in a vast theater, the enemy's defensive planning becomes far more challenging due to the unpredictability of the threat.

Very few details of the Navy’s NGAD program have been revealed so far, so we have little idea about what kind of drones it’s expected to include. At the same time, the Navy’s current ‘flagship’ aerial drone, the MQ-25, has seen its planned initial operational capability date slip from 2025 to 2026 due to manufacturing issues, indicating some of the challenges that could lie ahead. Still, the USAF and the Navy are seeing advanced unmanned capabilities as absolutely critical to winning a future near-peer fight, so these capabilities are being rushed into the operational realm.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WFrzKILwfFg

Whatever the Navy’s future combat aviation plans look like, it’s now clear that its aspirations to field advanced uncrewed aircraft aboard its supercarriers could just be the start of a much wider effort that could see a potentially vast range of drone capabilities flying from many different ships, with the aid of novel aircraft launch and recovery systems.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com