A Navy base put up a wall to ward off stray bullets. Locals say that doesn't solve gun violence.

More than 20 shipping containers line the south side of a Navy base in Gulfport, Mississippi. They’re not there to transport goods, but instead stand as a silent marker of the gun violence afflicting the state’s second-largest city.

The hulking boxes were put in place last fall, after gunfire at a subsidized apartment complex across the street damaged five homes inside the Naval Construction Battalion Center; no one was hurt. The base responded by increasing patrols around its perimeter and making one of the most fortified areas of Gulfport even more so.

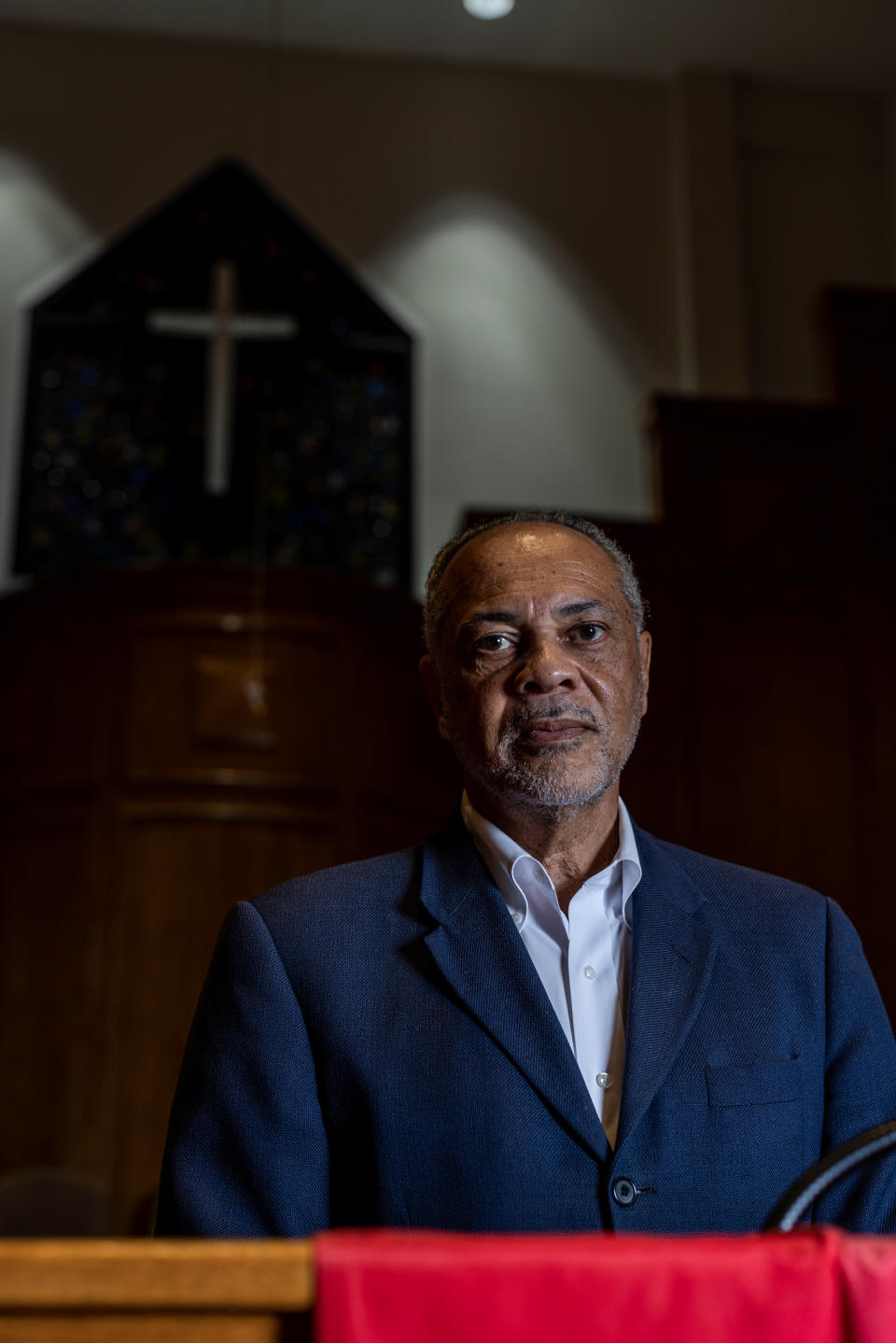

“The optics of that are very bad,” said John Whitfield, a pastor and the CEO of Climb CDC, a nearby nonprofit focusing on workforce development. “The practicality of it, I understand.”

A spokesperson at the base said the barrier is meant to be a “temporary solution” and that the city had offered assurances that it was addressing the gun violence issue. Still, the Navy is considering building a permanent concrete wall.

“The force protection of our base, personnel, and families is our highest priority,” Becky Shaw, the spokesperson, said in an email.

The shipping containers are just one indicator of the grinding toll of gunfire afflicting parts of Gulfport, a vibrant beach town of about 72,000 on Mississippi’s Gulf Coast.

Residents and workers in the city’s most impoverished areas detailed the recurring snap of gunshots, incidents in which apartments have been struck by stray rounds, and the increasing frustration of the young and old alike having to scramble for cover when someone opens fire. They also described the dual tragedies of teens losing their lives at the hands of their peers, who end up facing lengthy sentences in prison.

A decade ago, Gulfport, where more than half of residents are white and nearly 40% are Black, reported two or three homicides a year. Since 2019, there have been at least 10 killings per year.

In a city where about 26% of residents live in poverty, many see a link between economic hardship and gun violence.

“Some of our children and some of your young people are just helpless and hopeless,” said Sonya Williams Barnes, a former legislator who lives in Gulfport and is the Mississippi state policy director for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Gulfport is three hours south of Jackson, the capital, where the homicide rate is more than six times higher than in Gulfport. But while Jackson has had a more visible struggle with public safety, residents and community leaders in this coastal town say they, too, have grappled with gun violence for years.

Late Thursday evening, two people were injured in a shooting at a birthday party a few blocks from the Navy base's shipping containers, and shortly afterward a 20-year-old man was shot and killed in a separate incident nearby.

On April 30, a pregnant 16-year-old, JaKamori Lake, was shot and killed in another part of Gulfport; police charged a 15-year-old in her death. A few days earlier, Gulfport police arrested a seventh suspect from a New Year’s Eve 2021 shooting that left four people dead.

“It may not be as bad as Jackson, it may not be as bad as Memphis, Tennessee, but we’ve got that problem,” said Louis Gholar, president of the West Gulfport Civic Club, who helped organize an upcoming community meeting about violence prevention. “I think not just in Gulfport — the whole coast has that problem.”

In April, five people were injured in a shooting during the popular Black Spring Break event in Biloxi. Two weeks later, a 19-year-old gunman in Bay St. Louis allegedly shot and killed two teenagers and injured four others at an after-prom party. And in May, a shooting during a Cinco de Mayo party at an Ocean Springs bar left a 19-year-old dead and six others wounded.

Tia Mosley, whose 17-year-old son, Caleb, was killed two years ago in a drive-by shooting in Gulfport, said that every time she opens Facebook and sees more news of local violence, anxiety washes over her.

“It makes me not want my daughter to go outside at all,” she said of her 11-year-old. “All you can do is pray.”

Gholar is troubled that many of the victims and suspects in Gulfport in recent years have been teens. Last October, a Gulfport police officer shot and killed a 15-year-old who officials say was armed; a grand jury declined to indict the officer.

“We’re losing our young people too fast, too quick,” Gholar said. “They don’t even get a chance to live.”

Gulfport Mayor Billy Hewes, a Republican who is in his third term, agrees that gun violence is a concern. In some cases, issues arise when apartment complexes lack adequate security, his staff said. The mayor’s office also mentioned boys and girls club programs for at-risk youth and said churches have stepped up to offer support.

But the mayor believes the solution is more a matter of personal responsibility — parents keeping a closer eye on their teenagers and intervening if they discover guns.

“That’s where I think we start having problems, when we rely on government to solve everything,” he said. “Quite frankly, what I’ve seen and experienced and believe is that it starts at home.”

In Gaston Point, a historically Black middle-class neighborhood in Gulfport, some say that’s just part of the picture.

Martha Lockhart-Mais, a retired schoolteacher, said it’s also a question of how parents are supported in caring for their children. Teens need somewhere safe to go after school, she said.

Others in the community mentioned the need for mentors and conflict resolution resources. Some suggested restorative justice, which allows for teens accused of nonviolent crimes to be subjected to an alternative criminal justice system.

Lockhart-Mais, who said one of her former students was shot and killed last year and several others have been involved in shootings, lives not far from the Navy base and the shipping containers.

“I don’t like walls that separate people,” she said. “I feel that people should be able to live together without having a barrier.”

Ahead of last week's shootings, she and other neighborhood residents said the previously frequent gunshots had tapered off after the wall of containers was put up last fall.

William Bell Apartments, where much of that gunfire originated, has increased its security, local officials said, and the city has banned parking in a nearby zone to prevent loitering.

Several miles away, in another part of West Gulfport, Bettie Ewing, a retired housing rights organizer, is frustrated by how quickly the shipping containers went up to protect the Navy families, when there’s nothing similar to keep her home safe.

She said the barrier sent a message: “We’re going to protect the military, but the civilians, we’re just going to let them be.”

Since 2020, three people have been shot and killed at Emerald Pines, the subsidized apartment complex where Ewing lives. This year, the Gulfport Police Department’s online crime map notes seven incidents of shots fired on the blocks around the complex, though Ewing and others said the gunfire is more frequent.

A spokesperson for Emerald Pines’ management company said the company uses security cameras and has requested increased police presence near the complex.

A spokesperson for the Gulfport Police Department said officials meet regularly with the complex’s management, but that having an onsite surveillance system is “not the entire solution.”

“Management must limit access to the complex and hold problem tenants and their guests accountable,” Gulfport Police Sgt. Jason DuCrè said in an email.

Emerald Pines is in a census tract where almost 60% of residents live in poverty, more than twice the rate in Gulfport overall.

Jalisa Jackson, a certified nursing assistant who moved into the complex this year, said one shooting left a bullet hole near her door. On another occasion, while she was hosting a girls’ night, she and her guests scrambled to the floor after hearing gunfire. By the time bullets flew past her window, the mother of four had had enough.

“Just because we’re in a neighborhood like this doesn’t mean we should be subjected to harm,” she said. Jackson added, “We’re in the crossfire and it’s not fair.”

Jackson recently moved her family two hours away to McComb, Mississippi, where she currently works.

When considering how to stop gun violence, few in Gulfport mention gun control. Some said they’d like to see a waiting period for firearm purchases, but the Republican-led state has an open-carry law, and a 2020 attempt to restrict access to guns for those who may be in danger of harming themselves failed in the Legislature.

State Rep. Jeffrey Hulum III, a Democrat from Gulfport, said he wants to see fewer guns “on the street.” The representative, who operates a food assistance nonprofit and also offers firearm training courses, added that he supports a gun buyback program, better mental health services and more funding for the state’s crime lab, which has struggled with a backlog of autopsies.

In some of the most vulnerable blocks in Gulfport, Hulum added, there are aging apartments that should be torn down. People there are already “going through life with life hitting them with generational neglect,” he said.

Gulfport native Jeffery Hill had just graduated high school when he was convicted of manslaughter, ultimately spending 22 years in prison.

He believes there needs to be more assistance for people trying to climb out of poverty, including better transportation to get to work. He also wants to see more spaces for teens to hang out, like arcades and community gyms.

Hill, who was released in 2017 and now lives in Laurel, about 100 miles away, still has family in Gulfport. He hopes to return in the coming months to speak with young adults at William Bell Apartments about handling disputes without violence.

“I am the perfect example of what guns can cost you in life,” he said.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com