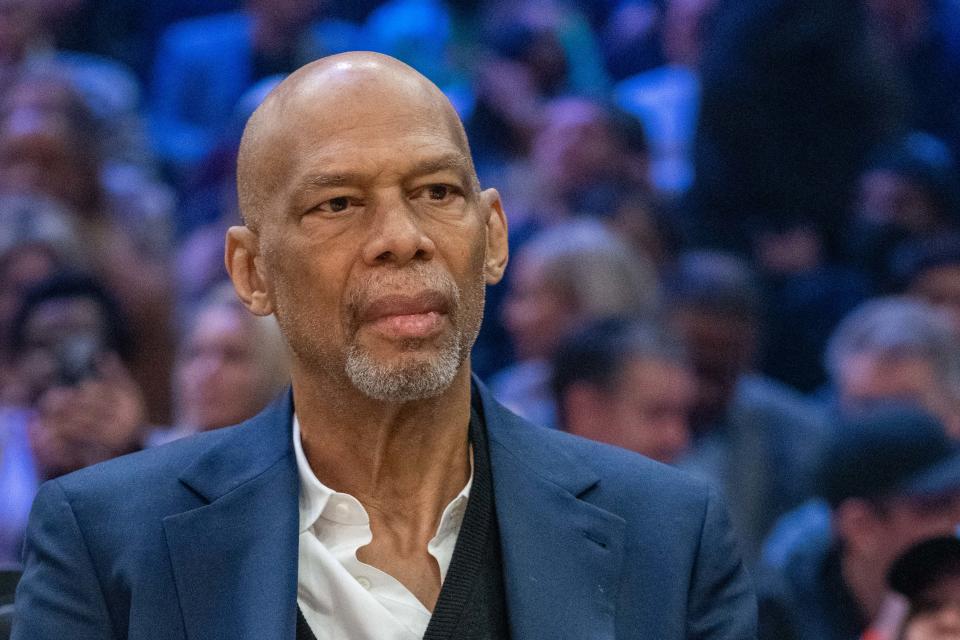

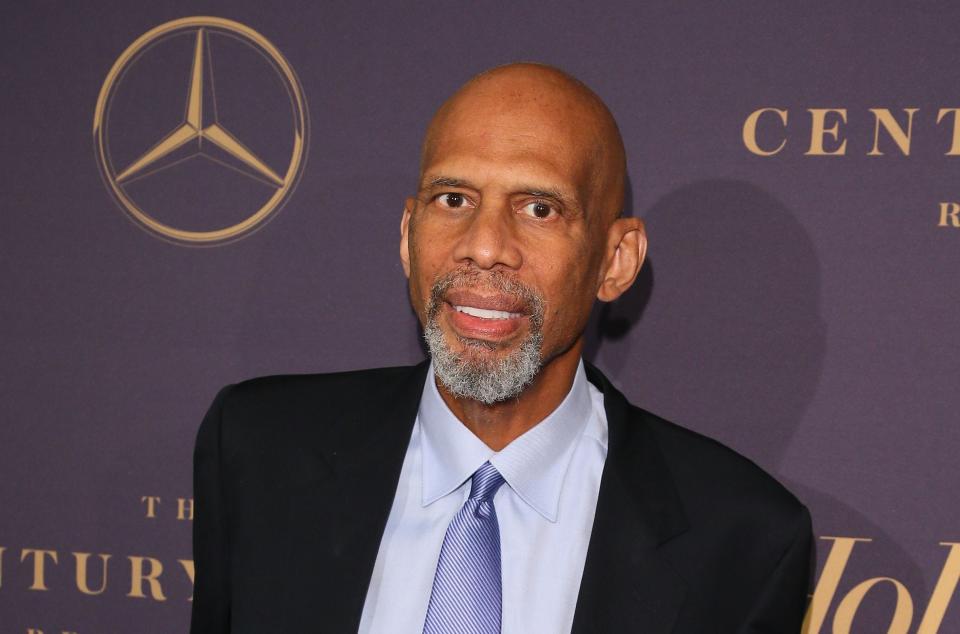

NBA great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar's fight for social justice has always been about sacrifice

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1968, Lew Alcindor, a UCLA junior, declined to represent the United States in basketball at the Olympics in Mexico City. While the college superstar saw it as an appealing opportunity, he didn’t have the enthusiasm to compete for a country that was denying rights to Black people.

Three years later, Alcindor changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and went on to become an NBA legend, amassing a list of achievements on the hardwood longer than his 7-foot, 2-inch frame. But despite all the awards and six championship rings, the Lakers great has sought to define himself as “someone more than the guy with the skyhook,” referring to his signature shot.

Long before Colin Kaepernick

Understandably, much of the talk these days about athletes being advocates for social justice has centered on Colin Kaepernick. While Kaepernick's story is important, its outsized attention can crowd out the rest of the picture: Athletes have been using their platforms to bring awareness to civil rights and inequality long before the San Francisco 49ers quarterback, in 2016, declined to stand during the playing of the national anthem to protest police brutality and racial injustice.

Rex Huppke: On a college visit with my son it hit me. He's ready. And I'm not.

In an interview conducted by exchange of emails, the NBA’s all-time leading scorer shared his path to becoming a social justice advocate and how today’s athletes can build on what he and others started.

Roots of an NBA legend

Abdul-Jabbar’s decision to sit out the Olympics was made under a public spotlight. But his contemplation of racial issues began in a solitary way – and before his days on the Westwood campus. While in high school in New York City, the future 19-time All-Star came to the realization that Black history was largely ignored in the curriculum.

To put it another way, in "Black Cop’s Kid," Abdul-Jabbar’s 2021 essay, on the influence of growing up the son of a Gotham police officer, he asks, “If a Black person does something amazing in a forest and no one talks about it, did it happen?”

“When a child goes to school and there’s nothing in the textbooks or classroom about anyone who looks like them,” Abdul-Jabbar said, “they start to have self-worth issues.”

He fears that kids will wonder “if maybe they really are inferior and that people aren’t being racist, just telling the truth. They grow up doubting their ability to achieve, to do anything great, to be worth having a job that a white person does.”

This, Abdul-Jabbar said, “robs us of both our heritage and our future.” He called his writings – which are prolific on social justice and the role of race – “an attempt to set the record straight in order for African Americans to reclaim their culture and celebrate their achievements.”

Let's help teachers: Teachers are suffering, so we're putting our appreciation into action

Abdul-Jabbar’s Olympic boycott is linked to Muhammad Ali’s decision, a year earlier, citing religious reasons, for refusing to be inducted into the U.S. Army. The heavyweight boxing champion was convicted of draft evasion, stripped of his title, barred from boxing and sentenced to five years in prison. Ali stayed out while his case was appealed and his conviction was eventually overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Jim Brown, who had recently retired as the National Football League’s leading rusher, convened a meeting in Cleveland of several high-profile athletes, Ali included, to decide whether they should support the boxer’s decision. Despite his youth, Abdul-Jabbar was invited to what is now known as “the Cleveland Summit.”

'The meaning of protesting and the importance of sincerity'

That gathering, Abdul-Jabbar said, “threw me in with a lot of passionate, articulate and intelligent athletes.” He said the discussions “went on for hours as we dug deep into the meaning of protesting and the importance of sincerity.”

“It made me realize that being an elite athlete came with a lot more responsibility than I had ever imagined,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “Of course, it would be easy to just virtue signal by saying all the right things and donating money to all the right causes. But these men had waded into some turbulent waters up to their necks in order to help others. I knew that I could do no less.”

CIVIL RIGHTS: Even before Brian Flores' lawsuit, NFL had a long road to integrating its football teams

The history of athlete advocacy is now getting attention in academic circles. Len Elmore, a first-round pick in the 1974 NBA draft who went on to Harvard Law School after his 10-year pro career, teaches a graduate-level course on the subject in the sports management program at Columbia University.

In a phone interview, Elmore described his class as tracing athlete activism, starting as far back as post-Civil War reconstruction, “against the backdrop of social, political and economic events in America.” What it reveals, Elmore said, is that sports activism “paralleled what was going on in the United States” at the same time.

Elmore said that “athlete activism is not going anywhere,” and that his students – future sports executives – can use this history “to have a better understanding of how to effect change.”

Taking a risk

College players today, using their social media megaphone, can wield influence over a wide audience. I asked Abdul-Jabbar if, as in his own case, this is where athlete advocacy should begin.

History: The attorneys who helped Martin Luther King build a movement

“We have to make college sports the ideal in terms of diversity and education, with the idea that the players who come out of those programs will demand the same from professional sports. If they continue to work as a team when they go pro, they have the power to bring about massive changes without fear of losing their jobs.”

In 2016, Abdul-Jabbar wrote, “What makes an act truly patriotic and not just lip-service is when it involves personal risk or sacrifice.”

But with Kaepernick’s actions likely being career-ending, how can athletes be persuaded to take such personal risks?

“I don’t want to convince athletes to take these risks,” Abdul-Jabbar responded. “I want them to come to the conclusion on their own, that it’s worth the risk if it means a better life for all people. I want them to come to that conclusion because I think they will be happier, more fulfilled human beings than if they just relied on fame to validate them.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams LLP in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Before Colin Kaepernick: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar fought for social justice