NC event named for Trump is trying to come back from the dead. It’s not going well.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

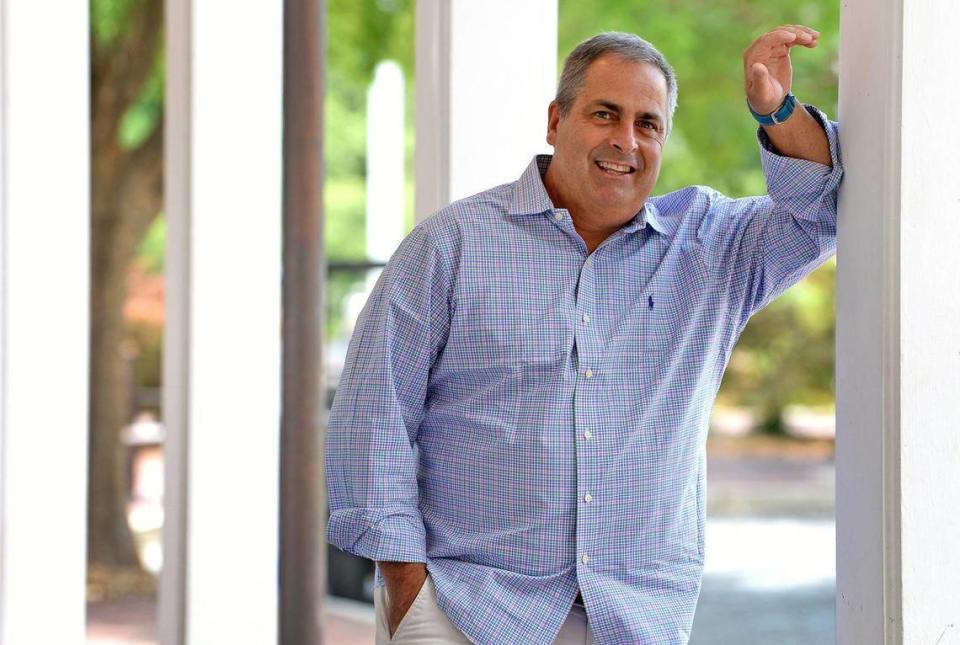

As far as Chuck McAllister is concerned, coming up with a name for a triathlon is so simple that a child could do it.

“I always use the comparison,” says the 56-year-old McAllister, “if I was holding it at the Walmart down here in Mooresville, it would be ‘Tri at the Walmart.’”

The reality is, however, the annual triathlon he is the founder and director of is not at the Walmart. It’s on Sunday, Sept. 26 at Trump National Golf Club, Charlotte in Mooresville, and while putting “Walmart” in the official title of his race could theoretically create its own unique set of issues for McAllister, one thing has been made painfully clear to him.

Calling it “Tri at the Trump” is much worse.

Since Donald J. Trump was elected president in 2016, McAllister has changed the name of the race and changed it back again, has canceled multiple times due to blowback over the name and the location, and has failed in his repeated attempts to grow the event beyond a few hundred participants.

Now, even though Trump is no longer in office, McAllister and Tri at the Trump are smack-dab in the middle of their most turbulent year yet. Sponsors and beneficiaries have unexpectedly cut ties to the race in recent months, as has the company that had headed up management of the event since its inception.

But what really has McAllister in panic mode is the fact that only 27 triathletes are signed up as of this week. In a normal year, he says, he’d expect about 125 to 150 people to have registered by this point, a little over 10 weeks out from race day.

Then again, because the Trump name became not just a turnoff but downright toxic to those who opposed him, and because McAllister has flip-flopped more than once on key decisions regarding the race, Tri at the Trump has rarely had anything close to a normal year.

All of which illustrates the unprecedentedly long shadows Donald Trump continues to cast, and begs the question: Can this event ever survive with this name, at this place?

How the race came to be

McAllister, a born-and-raised Long Islander and former Wall Street guy, moved from New York to the former The Point Lake Golf Club community in 2010.

He was making a career switch, becoming an executive at a company that makes shoe boxes for the athletic footwear industry, and just generally trying to shake the ghosts of 9/11, which claimed the lives of many of his former colleagues at Cantor Fitzgerald.

In the spring of 2012, the Trump organization bought the club for $3 million, then reportedly poured tens of millions into renovations; it retained the Nantucket-inspired architecture in its Village Square, but made scores of changes and improvements to the course and the facilities, including Trump-ian touches like adding marble floors and gold fixtures to the restrooms.

McAllister was an avid triathlete when he was in his mid-40s, and when he looked at its lakeside setting, the wide-shouldered, well-maintained roads leading to and from the club, and the shady golf-cart paths, he envisioned a first-class race at a first-class venue — with some serious brand recognition.

Sure, Trump’s pop-cultural relevance was on a slight decline, with the best days of NBC’s “The Apprentice” a few years behind him; but the billionaire was still someone who, during most of the first half of the 2010s, had a rock-star appeal.

Far more crucial than any connection to Trump, McAllister says, was the charity component.

“As soon as Chuck brought it to me,” recalls Gavin Arsenault, general manager of Trump National Golf Club, Charlotte, “with a landscape looking at fundraising for children suffering in our community ... that’s where I jumped on board. You know, I wasn’t thinking of a sprint triathlon, I was just thinking ... he had a vehicle to help children in need in our community.”

McAllister recruited four-time U.S. Olympic triathlete Hunter Kemper as a partner in the race, a sprint triathlon featuring a 750-meter swim, 13.25-mile bike ride and 5-kilometer run. He designated a charity devoted to helping kids with cancer, the Pinky Swear Foundation, as the beneficiary. And he came up with a name — Tri at the Trump — that was simple, muscular-sounding, neatly alliterative.

“Obviously,” Arsenault says, “in the early years, that name was fine. Till we really got into some of the politics.”

Aboard ‘The Trump Train’

Nearly 300 athletes participated in the inaugural edition of the race, on May 17, 2015, navigating a course that saw them running barefoot and dripping wet through the club’s ostentatious Lakefront Ballroom and underneath a colossal chandelier as they transitioned from the swim finish to their bikes in the parking lot.

One month later, at a campaign rally and speech at Trump Tower in New York City, Trump formally announced he was running for president.

The next year, McAllister shifted the event to the fall, and designated several charities as beneficiaries — including the Hemby Children’s Hospital and the Isabella Santos Foundation, both based in Charlotte — instead of just one. Registrations for the Oct. 2, 2016, race dipped by more than a third over the previous year, to about 180 participants, in the midst of a campaign cycle during which Trump repeatedly courted controversy with derogatory remarks about everyone from Mexicans to Fox News’ Megyn Kelly.

Just over a month after that, Trump won the election. With a little bit of help from McAllister.

To explain: During the middle of 2016, McAllister took a break from his day job to organize support for Trump’s run for the Oval Office, his main interest in helping Trump get elected being the candidate’s pro-small-business ideas.

With his wife Connie, McAllister co-hosted an August fundraiser at Trump National Golf Club that reportedly generated more than $1.4 million for Trump’s campaign. He also took an old Ford RV and wrapped it with American flag imagery, the words “The Trump Train,” and a Trump-Pence “Make America Great Again” logo, then drove it around North Carolina to park it prominently in lots outside campaign events for assorted Republican candidates that summer and fall.

Yet “there were many mornings I woke up when I was working and I’m going, ‘What the (expletive) am I doing this for?’” McAllister admits. “This guy is making these comments. He’s killing everything we’re trying to do to help him to get him in the office, and he’s coming out with these things.”

After the election and the inauguration, Americans quickly became fiercely divided over Trump, the dissension marring holiday dinners, casual Facebook discussions, and — eventually — a small triathlon in North Carolina.

Turbulent times for the tri

McAllister said he was inundated with complaints about the name of the race during the summer of 2017. So that September, less than a month before race day, he changed it to Tri for Good.

It’s a decision Arsenault, the GM of Trump National, supported.

“If he was sticking true to the charity and the people participating I knew would have a great time, I could care less what the name was,” Arsenault says. “I surely didn’t need to bring any ill will because of the politics of the name to lessen the opportunity for charity for kids.”

But McAllister quickly changed it back, he says, after Trump supporters harshly derided the decision. Before the month was over, he announced the event was being canceled, saying then that he had “received numerous politically charged threats.”

At the same time, he promised the race would return to serving triathletes and helping kids with cancer in 2018, and it did, again raising money for the Isabella Santos Foundation while adding a new twist: In partnership with Queens University of Charlotte’s triathlon teams, the event would host dozens of collegiate athletes on the same course at the same time, in what would be a regular-season race on several schools’ schedules.

Though McAllister continued to get flack over the name, Tri at the Trump settled into a groove in 2018 and 2019, embracing its reputation as a well-reviewed event thanks in part to surprisingly lavish amenities and giveaways for a small race.

The college piece of it proved to be successful, too — also in spite of the reservations of some.

“I answer this question to college coaches all the time who may take issue with it,” Queens coach Sonni Dyer says, “and I say, ‘We have to understand that it is a location, number one, and number two, that the purpose of the event is to benefit charity.’

“So we can get hung up on the integration of politics and sport all we want, but let’s don’t forget the fact that this event — whether you like the name or don’t like the name, whatever — that it is ultimately to provide college kids an opportunity to compete at a great venue, who is graciously hosting for the purpose of raising money for charities.”

2019 would in fact prove to be the race’s most successful year, with more than 300 participants.

The 2020 edition, however, was canceled due to COVID.

So when 2021 started, with Trump on his way out and vaccines on their way in, McAllister saw 2021 as being full of potential for his event. Maybe even a breakout year.

Then Trump held a rally in the middle of Washington, D.C., where he repeatedly made debunked claims about election fraud; shortly thereafter, hundreds of his supporters breached police perimeters outside the Capitol and stormed the inside as Congress was beginning the Electoral College vote. As a result, five people died.

Shortly thereafter, folks who had stood by McAllister’s race for years decided they could no longer do so.

‘We had to walk away’

“I will say that Chuck truly loves this event, and he’s always done a great job of really making it memorable for participants,” Hope Jones wrote in an email to the Observer this week. With her husband Benji, Jones co-owns the Greensboro-based Jones Racing Company, which has managed and timed all four previous runnings of Tri at the Trump.

“But the event has reached a point where it cannot be separated from the brand (and) what the brand represents for a lot of people.”

“After the insurrection on January 6, incited by his election lies and inflamed by his rhetoric, we had to walk away,” Hope Jones explained in her email. “We obviously take a financial hit in an already financially hard time by doing so, but it was time to let this one go. Too many people have been harmed and continued be harmed in his name. We don’t want to add to that.”

Jones Racing Company informed McAllister of its decision on Jan. 11.

Two days later, one week after the unrest at the Capitol, McAllister announced he was canceling Tri at the Trump. Again. This time, he said, for good.

Once again, though, he couldn’t stay away.

Trying for a fresh start

In early March, he resurfaced to add a post to the event’s Facebook page, which had gone dark since the cancellation: “Thank you for all the positive feedback about putting the race back on,” McAllister wrote. “We are doing our best to see if we can make it happen.”

Three days later, he posted a redesigned logo for the race with a save-the-date for Sept. 26, 2021.

As it turned out, McAllister had changed his mind after trusted friends encouraged him to stick with it, and after ultimately deciding, he says, that “raising money for kids with cancer and putting on a first-class race” were too important for him. That putting up with people’s issues with the name of the race and the location were worth the trouble.

He secured a new race management company — Trivium Racing, of Greensboro — and the Tri at the Trump train was steaming ahead again.

Says Richard Swor, who co-owns Trivium with his wife Libby: “Without going into any type of detail, my politics definitely don’t align with Donald Trump. ... But what kind of just put us over the top ... is that the money’s going to a really good cause and all the people involved that we got to meet with were good people and cared about good things. I don’t know. I’ve never seen politics play such a huge role in a sport before, and I guess we might be in that place, but we weren’t ready to make a decision based on that.”

Others, however, were ready to.

Another longtime partner in the race, the nonprofit Isabella Santos Foundation — which is dedicated to raising funds to support children with neuroblastoma and other pediatric cancers — cut ties with Tri at the Trump in 2021 after multiple years of being a charitable beneficiary.

“Chuck wanted us to be involved this year,” says Isabella Santos Foundation president Erin Santos, “but we unanimously said that we just can’t be associated with anything political.”

“I know him personally and I know that he’s just such a good guy when it comes to wanting to do things for people,” she adds. “And I think that’s what’s hard for me, is that I think it’s just this veil that kind of falls over the top of him because of this name, when I really know him as a person and have developed a friendship with him and know that he’s really just trying to do good, in a time when there isn’t a whole lot that is good.”

McAllister also says Novant Health, which in past years has made in-kind donations as a sponsor of the event, declined his plea for assistance this time around. He says he was told it was due to “the circumstances of the election.”

A Novant Health spokesperson confirmed the hospital system had sponsored Tri at the Trump in the past, and that it did decline to do so this year, noting that “that there were other events/sponsorships/partnerships that Novant Health supported in the past, but declined support of this year.” The spokesperson did not comment on the election or mention Trump.

In a statement to the Observer, Ann Caulkins, president of The Novant Health Foundation, said: “We evaluate each sponsorship opportunity case-by-case and year-by-year. This past giving cycle occurred in the midst of an unprecedented year — from a global pandemic to social unrest. As such, our giving and priorities shifted, but we remain committed to providing thoughtful and thorough consideration to all community partners.” (Caulkins was formerly publisher of The Charlotte Observer.)

So where does that leave McAllister and Tri at the Trump?

‘I’m not gonna be quitting ever again’

There are still plenty of sponsors attached. The presenting sponsor he has secured leans even further into the name — it’s Trump International Realty Charlotte — but Dick’s Sporting Goods is again a major sponsor and businesses like Five Guys and Metrolina Greenhouses remain involved.

Curetivity, another nonprofit dedicated to fighting pediatric cancer, is the beneficiary this year.

Dyer, the Queens triathlon coach, says the current plan is to return with his men’s and women’s teams, and to once again arrange for athletes from other colleges and universities to join them. If that happens, McAllister says, roughly 200 collegiate-level triathletes will wind up being registered for the event.

Right now, though, he has just 27 total athletes signed up. That’s barely enough to fill a Major League Baseball team’s roster.

And he’s not an idiot. He knows one of the reasons for the sagging numbers.

“Oh, every day I worry about the name,” McAllister says. “I mean, I wake up, the first thing I do is I pull up my (sign-up list) for the race, to see what’s going on, to see what I have. And it’s disheartening. I mean, I went 13 days where I didn’t get one sign-up in the last week and a half. That sucks. Because by only having that number, it affects ... what I can give to the charities, and I’ve raised a (lot) of money for these charities as a one-off triathlon. Over a half a million bucks ... since (its inception).

“So yeah, I’m worried about the name every day. Every day.”

But, he says, he’s not changing it again. Not unless it moves to the Walmart. The name is the name, he says — it works. And he thinks he’ll catch just as much grief if he changes it again.

He also says he’ll never give up on the race again.

“I promise you. I promise you,” McAllister says. “I’m not gonna be quitting ever again. The race will go on until it can’t go on anymore. But it’s not gonna be because of lack of my efforts or because of any bulls---.”

He maintains that “my political affiliation ... has nothing to do with this race, and it never will.”

In fact, as a result of everything he’s experienced with the race over the past few years, McAllister — a guy who in 2016 helped fill Trump’s war chest and who decorated an RV to show his support — has become something he might never have anticipated:

Disillusioned.

“I just hope the guy doesn’t run again,” McAllister says of Trump. “I mean ... stop! ... He keeps going back and forth. And I’d rather he just stays away. Man. It’s harder for everyone.”

He sighs, and pauses. “One thing I’ve learned is I’m staying away. I stay away from politics.

“I’ve realized,” he says, sighing again, “I hate ’em all.”