NC prisons ordered to show how they’ll prevent outbreaks as inmate complaints mount

As inmates across North Carolina complain that too little has been done to curb the spread of the coronavirus, a judge has ordered public officials to turn over detailed information laying out what they are doing to prevent outbreaks in state prisons.

The ruling by Superior Court Judge Vinston Rozier, issued Friday in response to a lawsuit filed by the state conference of the NAACP and other advocacy groups, comes at a time when prison leaders are grappling with two major outbreaks.

One of them is at Neuse Correctional Institution, in Goldsboro, where more 460 inmates have tested positive and two have died. The other is at the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women, in Raleigh, where 90 inmates have been diagnosed.

The judge’s order gives the state prisons until Friday, May 8 to provide information about whether each prison provides:

▪ Face masks for inmates “of the same type and quality as those provided to staff.”

▪ More than one face mask per person.

▪ Unrestricted access to sanitation supplies, including hand soap and hand sanitizer.

▪ Living conditions designed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Specifically, the order says the state should provide information about whether each prison has reassigned bunks to allow for six feet or more between occupants.

In interviews with the Observer over the past month, more than a dozen inmates have contended that their prisons have fallen short on such measures.

Some have complained that inmates lack access to disinfectant inside their dorms, and that the phones shared by prisoners are rarely disinfected between uses. Many have said their bunks are just an arm’s length away from those of other inmates.

At Neuse Correctional Institution, the site of one of the largest COVID-19 outbreaks nationally, two inmates contended that frequent transfers of inmates from dorm to dorm have increased the chances of spreading the virus.

“I’m thinking the people who don’t have it are going to get it,” said Zakiem Rogers, an inmate at Neuse. “That’s my fear.”

And at Caledonia Correctional Institution, an Eastern North Carolina prison where 17 cases have been reported, several inmates have said they sleep on bunks about three feet apart from one another.

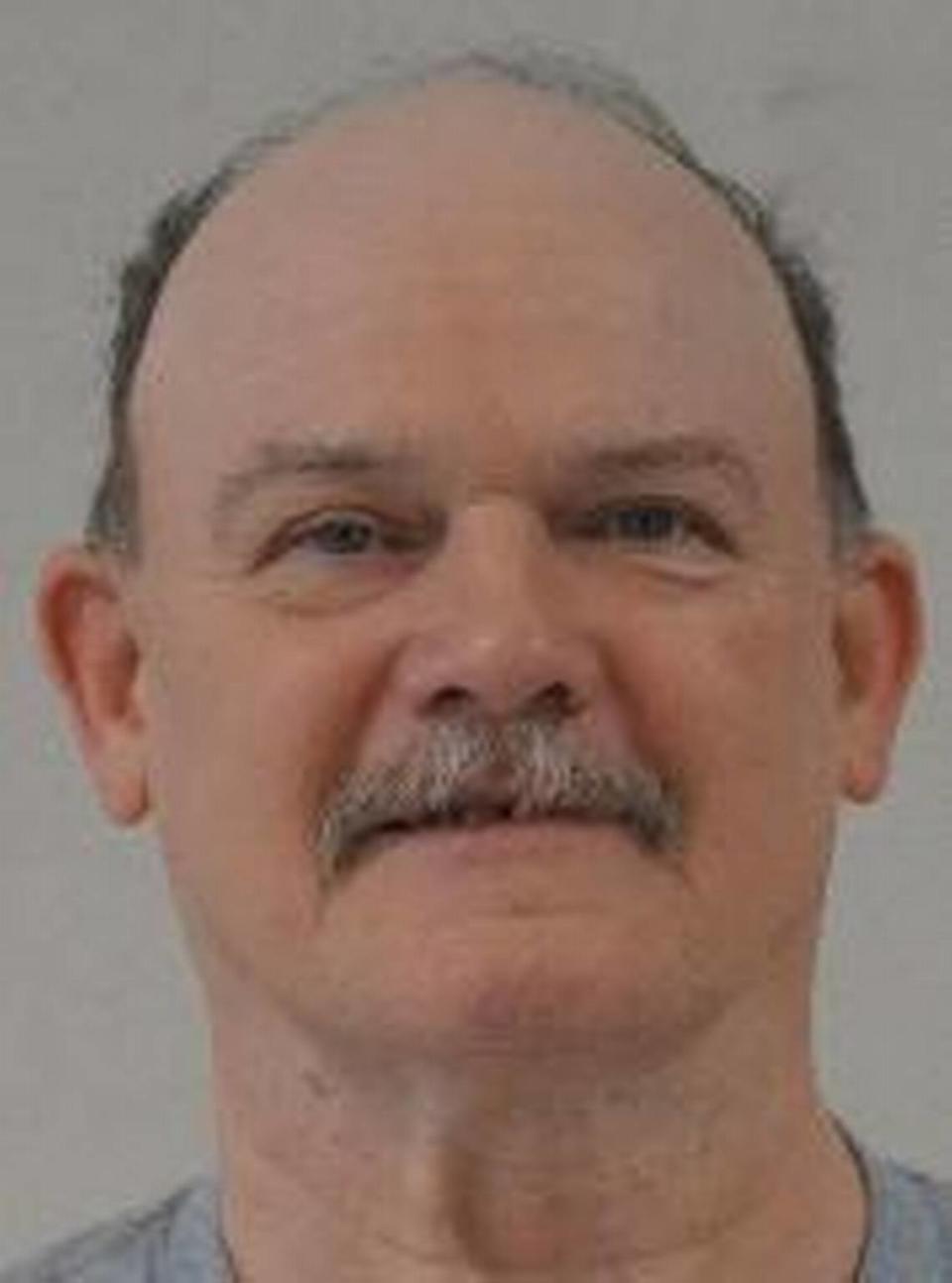

“The Governor or North Carolina and politicians ... must see that the prisons will be the place of death unless they do something about this,” 62-year-old inmate James Ronquest wrote in a letter to the Observer. “We must be separated.”

Prisons and jails are breeding grounds for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases because inmates lives so closely together, experts say.

State prison officials say they have taken a host of steps to prevent the spread of the virus. They’ve suspended visitation, along with the prison’s work-release program. They’re taking the temperatures of staff members before they enter the prisons each day. And they’ve sharply limited the transfers of inmates from prison to prison, and from county jails.

Inside Corrections Enterprises plants at various prisons, state officials say, inmates are manufacturing disinfectant, hospital gowns and thousands of face masks to protect both prisoners and staff.

But some inmates say they have been given just a single mask. And at the women’s prison in Raleigh, the site of the state’s second largest prison outbreak, several inmates said they weren’t provided masks until April 15 — long after COVID-19 had crept into the prisons.

Across the state prison system, more than 620 inmates have tested positive. While COVID-19 cases have been reported at nine state prisons, more than a third of the state’s 53 prisons have yet to test a single inmate.

State officials say they’ve begun early release of some inmates convicted of non-violent crimes who are considered to be high-risk for virus complications.

But in their lawsuit against Gov. Roy Cooper, N.C. Department of Public Safety Secretary Erik Hooks and four parole commissioners, the advocacy groups contend that the state’s plans will not provide adequate social distancing to keep inmates safe.

“The rampant outbreaks we’re seeing in state prisons are an imminent threat to people inside and outside of these facilities – with communities of color disproportionately at risk,” said Kristi Graunke, legal director for the ACLU of North Carolina, one of the groups that filed the complaint. “...Reducing the prison population is vital to saving lives and protecting public health.”

Dear readers: The Observer needs your help

Q&A: Charlotte’s projected coronavirus peak date moved. Why do the numbers change?