NC prisons scan letters, cards to disrupt smuggling. Could it alienate inmates — or save lives?

A new method for delivering mail to North Carolina prison inmates will help foil drug smugglers, state officials say. But critics worry that the change will further fray connections between prisoners and the outside world.

Under a change that went into effect on Oct. 18, inmates in the state’s men’s prisons are no longer getting the original cards and letters sent by their loved ones. They’re only getting scanned copies.

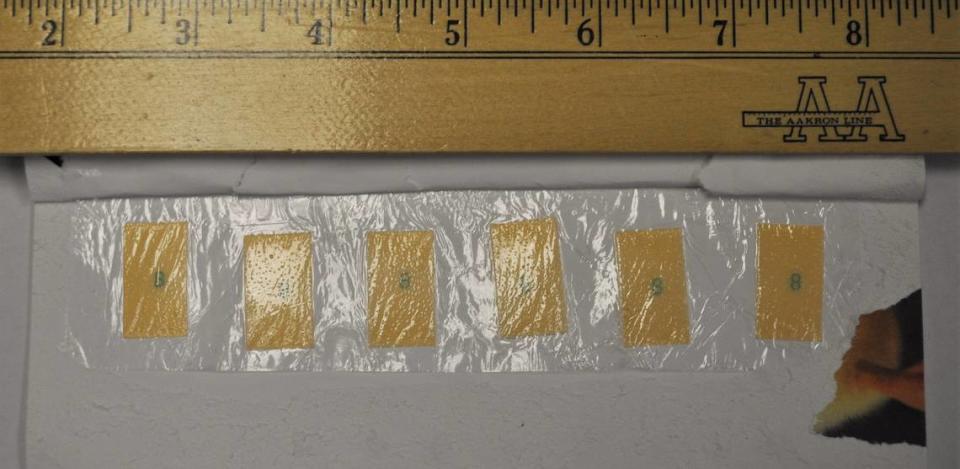

The system is designed to fight what state officials say is an increasingly common ploy for sneaking drugs into prisons. Smugglers are spraying liquefied drugs such as suboxone, fentanyl and K2 — all potent in tiny amounts — onto letters mailed to inmates, prison spokesman John Bull says. The inmates then tear the paper up and swallow the pieces.

“Contraband makes a prison unsafe in so many ways,” Commissioner of Prisons Todd Ishee said in a news release. “You have offenders struggling for control of the contraband trade. You have the risk of overdoses. Anything we can do to cut that off makes our prisons a safer, more secure place to live and work.”

But to Linda Hanson, a Concord resident whose son is now in prison, the change is “another step in dehumanizing” inmates.

Hanson usually sends holiday cards to her son and to others she has gotten to know in prison — “just to let them know somebody cares,” she said. Recently, however, when she was in the store looking at cards, she opted not to buy them .

“I was thinking, ‘What’s the use?’ ” she said. “It’s just so impersonal.”

The new system gives prisons a new surveillance tool, too. Electronic copies of letters sent to inmates will be kept on file for up to seven years, TextBehind spokesman Chris Reilly said. DPS officials can search those copies to assist in investigations. And if DPS officials approve it, outside law enforcement agencies could search them as well.

Under the old mail delivery system, “there may have been times when letters were kept if they were evidence in criminal investigations,” Bull said.

People sending mail to to incarcerated people need to be aware of the increased ability to monitor what they share, said Kristie Puckett-Williams, a manager with the ACLU of North Carolina.

“People have to be really careful about what they send in to loved ones so that it can’t be used against them or their loved ones or anyone else,” she said.

North Carolina is one in a growing number of state prison systems — including West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Wyoming, Colorado and Arkansas — that have switched to digital mail.

Here’s how the new system, piloted in women’s prisons since February 2020, works in North Carolina:

The tens of thousands of letters written to N.C. inmates each week will now be sent to TextBehind, a Maryland-based company that scans the letters in color and forwards digital files to the prisons. Prisons then print out scanned images and deliver the pages to inmates.

People who write to inmates have the option of mailing their letters, cards and photos to TextBehind, or sending them electronically, using the company’s app. The app lets users send digital letters, online drawings and electronic greeting cards. TextBehind charges fees, starting at 50 cents, to send electronic cards and letters. In either case, inmates should receive letters a day after TextBehind gets them, Bull said.

Attorneys can still send original paper letters and documents directly to their clients in prison..

The state prison system doesn’t pay for the new system or earn money from it, Bull said. Instead, TextBehind gets its revenue from the fees it charges for electronic messages.

In the first year after the system started in women’s prisons, disciplinary infractions for substance possession and use dropped by 50 percent in those prisons, according to the state Department of Public Safety.

Over the same period, staff in men’s prisons detected drugs or paraphernalia n the mail 568 times, the department said. The drugs most often found in the mail were Suboxone and K2.

Such deliveries too often prove dangerous. Drugs smuggled into the prisons typically lead to several hospitalizations each week, Bull said.

“This is key new technology to combat the age-old problem of drug smuggling in the prisons,” Bull said.

Historically, most of the drugs that have made their way into prisons have been smuggled in by staff members.

“I understand they have a problem with drugs,” said Malcolm Azariah, an inmate at Warren Correctional Institution, northeast of Durham. “But my experience is that most of it comes in through staff. It might slow things down. But I don’t think it will stop the problem.”

State prison officials say they’ve been working to prevent workers from smuggling contraband into prisons. It’s now standard practice for employees to search everyone who enters prisons, using metal detectors, body scanners and pat-downs, DPS officials say. The state has also beefed up fencing and added nets at prisons across the state to prevent contraband from being thrown to inmates.

Letters are ‘lifelines’

Similar mail-delivery systems in other states have been far from foolproof, critics say. The reproduction quality on scanned photographs has often been poor, making it hard to see people’s faces in photographs, they say.

And scanning glitches have left chunks missing from letters, says Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson for the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit working to reduce mass incarceration.

“What you might gain is not worth the sacrifice for incarcerated people,” Bertram said. “...We know that contact with people on the outside is critical to help people succeed after their release.”

Unlike some competitors, TextBehind offers reproduction that is “100 percent accurate,” Reilly said.

Still, inmates say, it’s not the same as getting actual letters and photographs. Azariah, the inmate at Warren Correctional, said he has seen scanned photographs sent to fellow prisoners. “They’re not bad,” he said. “But they’re nowhere near a glossy photograph.”

TextBehind receives mixed reviews from some users. The app that can be downloaded through Apple gets an average of 3.2 out of 5 stars. Some customers said it was convenient and reliable. Others said they ran into glitches that made it difficult or impossible to use.

TextBehind tries to resolve complaints immediately, Reilly said.

Launched in 2012, TextBehind began as a social media firm. The company made its first foray into delivering electronic mail to jail inmates in 2017. Its largest prison contract is with the state of North Carolina, Reilly said. The company also has contracts with the state of Wisconsin and with jails in about two dozen counties.

TextBehind has about 25 employees, but has not yet turned a profit, Reilly said.

“Our company’s goal is to make prisons and jails safer and to save lives — and to connect inmates and their families in an efficient and affordable fashion,” Reilly said. “And I feel we’re accomplishing that job.”

Others remain skeptical.

Mail is “one of the only lifelines that inmates have to the outside world,” according to Leigh Lassiter, a volunteer with the Prison Books Collective, a Durham nonprofit that sends books to inmates in North Carolina and Alabama.

Friends and family members can still send books directly to inmates in prison. But Lassiter is concerned about North Carolina’s new practice nonetheless.

“Imagine you’re working away from your family, and instead of getting mail with a crayon drawing from your child, you get a scanned version,” Lassiter said. “That is not even close to the same.

“Just holding a piece of paper someone wrote to you — that is a piece of human connection that should never be taken away.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was modified to include information about how scanned letters will be kept on file for seven years.