Neal Rubin: We can’t defeat spotted lanternfly that could plague Michigan wine industry

We’ve been warned before that spotted lanternflies are a threat to all that is holy and we should fight them with every weapon we can muster, including the bottoms of our shoes.

What I didn’t know until last week is that ultimately, they will defeat us, or best case, let us escape with a draw. We don't have enough technology, enough manpower or even enough shoes to chase them away, no matter that we already have the best slogans.

“Kill it! Squash it, smash it ... just get rid of it,” said the commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

"Stomp It Out!" said New Jersey.

"See it. Squash it. Report it," said our own state of Michigan.

Yet the spotted lanternfly, which apparently cannot read, continues its advance.

East Asian by origin, the lanternfly migrated aboard nursery plants and was first spotted in the U.S. nine years ago in Pennsylvania. It has since alit in 12 more states, with its one Michigan sighting at an abandoned industrial lot in Pontiac last August.

The alert nursery worker who came across it immediately instituted the correct emergency protocol, meaning he stomped on it, took pictures and notified authorities at the state's Eyes in the Field website. But where there was one invader, said Mike Philip, there are surely thousands more, threatening our grape crops, decks and cars while excreting a sugary water called honeydew that turns into a nasty black fungus called sooty mold.

Philip is an engaging fellow with two college degrees in insects who's high in the food chain at the Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development. Specifically, he directs the Pesticide and Plant Pest Management Division, which makes him the commanding officer in our war on bugs.

As the U.S. Department of Agriculture sounds its annual spotted lanternfly alarm nationwide, "Our goal is not to eradicate the insect," Philip said. "That is not really realistic."

Instead, he said, we need to contain the inevitable, limiting the lanternfly population as best we can while scientists work on better ways to annihilate the little cretins.

Knowing thy enemy

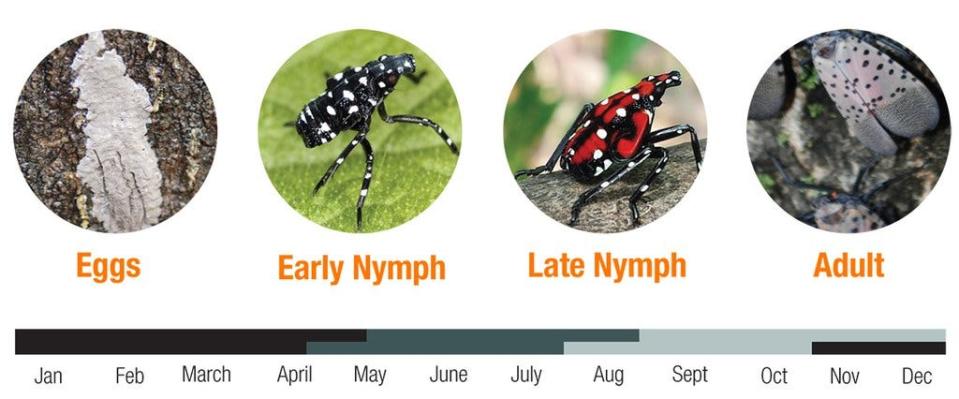

The spotted lanternfly is an inch or so long and half an inch wide, with large wings that hide its evil soul. The forewings are light brown, with black spots at the front. The hind wings are red, with black spots at the front and black bars at the rear.

Technically, "it's not a fly," Philip said. "To get a little bit entomological, it's more closely related to a cicada."

Also, it's more of a leaper than a flier, but it's a skilled hitchhiker, tucking itself inside wheel wells or bumpers. Its clusters of 30 to 50 white eggs look like a wad of gum and are even more portable, sticking to things like the sides of trucks before the lanternflies hatch and begin their magical transformation from nymph to nuisance.

The lanternfly's preferred domicile is another invader, the tree-of-heaven, brought from Asia on purpose in the late 1700s before people started noticing that it smelled bad and spread like lava. In the absence of a tree-of-heaven, a lanternfly will settle for and on black walnut, river birch, willow, sumac, red maple and grapes, some of which hit closer to home than others.

More: Beech leaf disease found in southeast Michigan counties: What to know

More: Spotted lanternfly turns up in Oakland County; grape industry threatened

More: Spotted lanternfly, a crop-killing pest, is hitchhiking and hopping its way to Michigan

As of 2020, Michigan was graced by 10,900 acres of juice grapes and 3,375 acres of wine grapes. Growers and winemakers are already dealing with climate extremes and a fruit fly called the spotted-wing drosophila, a plague so vineyard-specific that it has evolved a barb on its nose to puncture thin-skinned fruits.

Busy as he already is with the fruit fly, wild turkeys, assorted other birds and roaming deer, “we are concerned about the lanternfly,” confirmed Mike Laing, whose title is Director of MAWBYness at Mawby Sparkling in Suttons Bay.

His guess is that the spotted lanternfly would find its way first to the juice grapes of southwest Michigan, then venture north to plague the wine industry.

“There will always be a pest that enjoys grapevines,” he said — and there will always be a fresh reminder that Mother Nature is a lousy business partner.

Helping lanternflies hurt themselves

One way to spot lanternflies is to look for trees-of-heaven. “It’s much easier to see a tree,” Philip said reasonably, “than to see an insect.”

Wherever spotted lanternflies linger in bulk, they’ve been known to dive-bomb passersby, and the sooty mold can attract wasps and hornets while it discolors decks, shrubs or 2022 Honda Accords.

In terms of fighting back, the state has weapons that a garden store doesn’t. When the specimen was discovered in Pontiac, Philip’s department removed a few nearby trees-of-heaven and injected the others with a pesticide that didn’t harm the host but left the turf littered with little lanternfly corpses.

“This insect being a sap feeder,” he explained, “it will puncture the twig with its piercing mouthpiece, and suck like a straw.”

For now, that's the highest tech available for the task. Defending grapes and other innocent parties remains a grassroots, hands-on pursuit.

"An alert public," Philip said, "is our most valuable tool."

Use your eyes and your cellphone camera, and worry not about a minor splatter beneath your otherwise pristine footwear, for these are the times that try our soles.

Neal Rubin is fond of grapes, particularly green ones, and is taking a potential lanternfly invasion personally. Reach him at NARubin@freepress.com, or via Twitter at @nealrubin_fp.

To subscribe to the Free Press for not a bunch, click here.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan won't be able to defeat invasive spotted lanternfly