Nearly all strides in equal voting access in Louisiana have come from federal intervention

EDITOR'S NOTE: This page is part of a comprehensive guide to voting rights across the U.S. and in Puerto Rico.

Attempts to reduce the power of the Black vote in Louisiana have been a nearly permanent feature of the state's political environment, beginning with disenfranchisement after the Civil War and then gerrymandering after the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Expanded Black voting rights or fairly drawn district lines to reflect the state's Black population have almost always come from federal intervention.

A brief period of access, in 1800s Louisiana

Black voter registration skyrocketed in Louisiana following the Civil War when the right to vote was extended to Black men in 1868.

From 1868 to 1896, Black men made up about 45% of Louisiana’s registered voters and were a significant part of the political process, creating interest groups and participating in Republican Party politics.

But the accessibility was short-lived as the state ushered in the infamous Grandfather Clause in 1898, which imposed education and property requirements on registrants whose fathers or grandfathers had not been registered to vote before 1867.

Black voter registration plummeted as a result, dipping to 4% of total registration by 1900 and marking a new era of disenfranchisement.

Though the state now had to pass disenfranchisement laws that weren’t racist on their face with the passage of the 15th Amendment, state officials were blunt about their intended effects.

The president of the Louisiana Constitutional Convention that enacted the Grandfather Clause, Ernest Kruttschnitt, was clear on the intention of the law: “Doesn’t it let the white man vote, and doesn’t it stop the negro from voting, and isn’t that what we came here for?”

Arbitrary tests and requirements disenfranchised Black voters

Though the Supreme Court struck down the Grandfather Clause as unconstitutional in 1915, Louisiana officials were steadfast in blocking Black people from the political process.

In 1921, the state ushered in “interpretation tests” for voter registrants, requiring them to “give a reasonable interpretation” of any clause in the Louisiana Constitution or the U.S. Constitution.

Those who administered the test had complete discretion over whose understanding they deemed inadequate.

Also, the state now gave political parties the authority to require “additional qualifications” from registered voters to participate in primary elections.

Louisiana’s Democratic Party made being white an additional qualification to vote on primary candidates. So even if a Black resident was able to pass the interpretation test, he would be barred from participating in the only meaningful election in a state then dominated by Democrats.

White-only primaries and interpretation tests were so effective in barring Black Louisianans from the political process that Black people never made up more than 1% of registered Louisiana voters from 1921 until 1944, when the Supreme Court struck down white-only primaries.

Black voter registration in Louisiana slowly increased as a result, reaching 13% of all registered voters by 1964. The gains were spread unevenly throughout the state, however.

In Tensas Parish, for example, a little over 1% of Black residents were registered to vote while well over 90% were registered in Evangeline Parish. This is because Black voter registration varied inversely with the presence of larger Black populations.

In other words, in places with more potential for Black residents to have an effect on the political process, the more barriers there were.

The Voting Rights Act brings surge of Black voter registrations

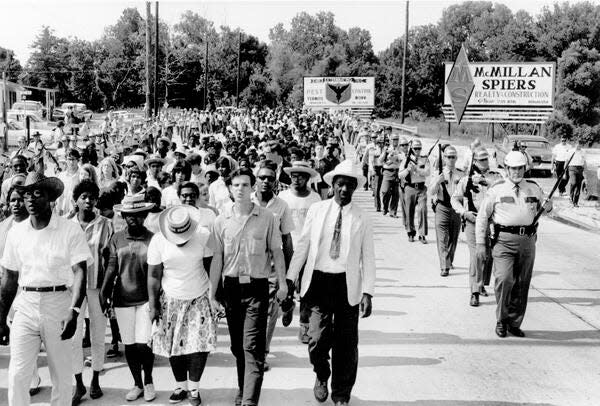

Louisiana and other southern states’ discriminatory practices led Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act in 1965, outlawing discriminatory voting practices and subjecting all voting changes in Louisiana to federal review.

The new federal law had monumental impacts on Louisiana, effectively eliminating the issue of vote denial in Louisiana. By 1967, Black voter registration increased by 84%.

Those gains continued until two-thirds of Black Louisianans were registered to vote by 1990. The number of Black elected officials in the state grew alongside the Black vote.

Although racial disparities in voting registration remain to this day, they are largely due to socioeconomic disparities rather than formal legal impediments.

But while the issue of disenfranchisement was a thing of the past, the issue of voting rights was not, as Louisiana officials learned that they could diminish the power of the Black vote by arranging election systems in a way that ensured Black Louisianans would cast meaningless ballots.

Louisiana legislature gerrymanders, dilutes Black voting power

The number of Black elected officials in the state grew steadily starting in 1972, reaching 527 in 1990, the third most of any other state at the time. Almost all of them were elected from a jurisdiction in which Black residents made up a majority of voters.

Louisiana officials looking to keep Black residents out of the political process after the Voting Rights Act would rely on this aspect of Louisiana politics to dilute the power of the Black vote.

Louisiana’s redistricting plans in the state House and Senate following the 1970 Census included maps that disadvantaged Black voters, submerging Black populations into large majority-white districts. In one case, a majority Black parish was joined with two white majority parishes in a noncontiguous manner, blatantly disregarding redistricting requirements.

A federal judge accused Louisiana of “employing gerrymandering in its grossest form,” and said that if the attorney general didn’t reject the plans, they would be deemed unconstitutional.

Louisiana officials tried, but failed, once again in 1980 to reduce the power of the Black vote, attempting to reduce the number of Black-majority districts in the Legislature from 17 to 14. The Department of Justice made the state revise its plan and add four more majority-Black districts.

By 1990, Black voters constituted a majority of voters in 15 state House districts and five Senate districts. In each of those districts, voters chose to be represented by a Black legislator.

In 2001, the state Legislature adopted a plan that allowed the electors of St. Bernard Parish to reduce the size of the parish school board and get rid of all majority-Black districts.

The new plan blatantly diluted the power of the Black vote in the parish. What made matters worse was the attitude of the highest ranking official in the parish, state Sen. Lynn Dean, toward Black people and the new changes.

While testifying in defense of the new map, Dean was asked if he heard the n-word used in the parish. He responded that "he uses the term himself" and "does not necessarily consider it a racial term."

Louisiana officials continue to go head-to-head with judges and the Department of Justice in redistricting plans.

Most recently, a Louisiana federal judge struck down the state’s Republican-drawn congressional map following the 2020 Census since it didn’t include a second-majority Black district before the U.S. Supreme Court put that order on hold until it can hear a similar case from Alabama this fall.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Daily Advertiser: Louisiana's long struggle with equal voting rights continues