'I needed to blend in': NJ Asians say they hid their heritage to survive in the suburbs

Saiful Khan remembers growing up in Jamaica, Queens, in a tight-knit Bangladeshi community until his family moved when he was in third grade. The relocation to Levittown, Long Island, would leave lasting scars.

Khan, who now lives in Montclair, recalled a walk home with his mother from the grocery store.

"A car pulled up, and someone threw hard-boiled eggs at her, opened up a laceration above her eye,” he recounted. “I was probably 8, 9 years old at the time. And that kind of informed how I felt about people in that town, so I totally hid who I was.”

The experience is one commonly heard from people growing up in communities not welcoming to immigrant families. It's the kind of prejudice cited in a recent survey by Asian Americans who said they sometimes felt compelled to hide their identity while growing up in the U.S.

The report, released in September by the Pew Research Center, said one in five Asian American adults had hidden a part of their heritage from non-Asians at some point in their lives. The nationwide survey of 7,006 Asian adults living in the U.S., conducted from July 2022 to January 2023, found that the pressure was felt most among younger respondents: 39% of those under 30 hid their culture, food, religion or clothing from non-Asians. That decreased with age: 21% of those ages 30 to 49 said they'd concealed aspects of their heritage, 12% of those ages 50 to 64, and 5% of people 65 and older. Thirty-two percent of U.S.-born Asian adults have hidden their culture, compared with 15% of immigrants.

Respondents cited reasons including "a feeling of embarrassment or a lack of understanding from others." More recent immigrants said they did so to fit into their new country, while U.S.-born Asian Americans with immigrant parents said they wanted to "avoid reinforcing stereotypes about Asians." Multiracial Asian Americans and those with more distant immigrant roots have "hidden their heritage to pass as white," the survey found.

The findings struck a chord with Asian Americans we interviewed in New Jersey. Three of them recently spoke with The Record and NorthJersey.com about their experiences.

Montclair man grew up in fear

Khan, 51, said he did whatever he could to hide his roots due to the constant harassment and discrimination his family endured in Levittown, the archetypical postwar suburb that had a history of officially excluding nonwhite residents.

"If I smelled like curry, I took two showers and lathered myself with soap before I went to school," Khan said. "When my family went to visit Bangladesh and did henna on our hands, I was very deathly afraid of going to school when I got back and prayed that the henna would wear off before anyone saw it and had a reason to poke fun at me and throw a punch at me."

Khan would overcome his fear and embarrassment about his culture as he grew older because of time spent in the Army. As he matured, he met people who wanted to know more about his culture, and he attended self-empowerment classes. He now works as an executive for New York City-based health insurance company Healthfirst.

Education: NJ students could soon be learning more about growing Garden State community of Sikhs

"I did some self-empowerment work, which opened my eyes to me not being my authentic self," Khan said. It "helped me discover all the baggage I was carrying from how I grew up."

But his transformation was not without regret. He felt that his earlier actions influenced his younger brother, who also hid his heritage when they were kids.

"I let other people dictate how I should have behaved and should have presented," Khan said. "Maybe I would have created a better path for my brother, who is five years younger than me."

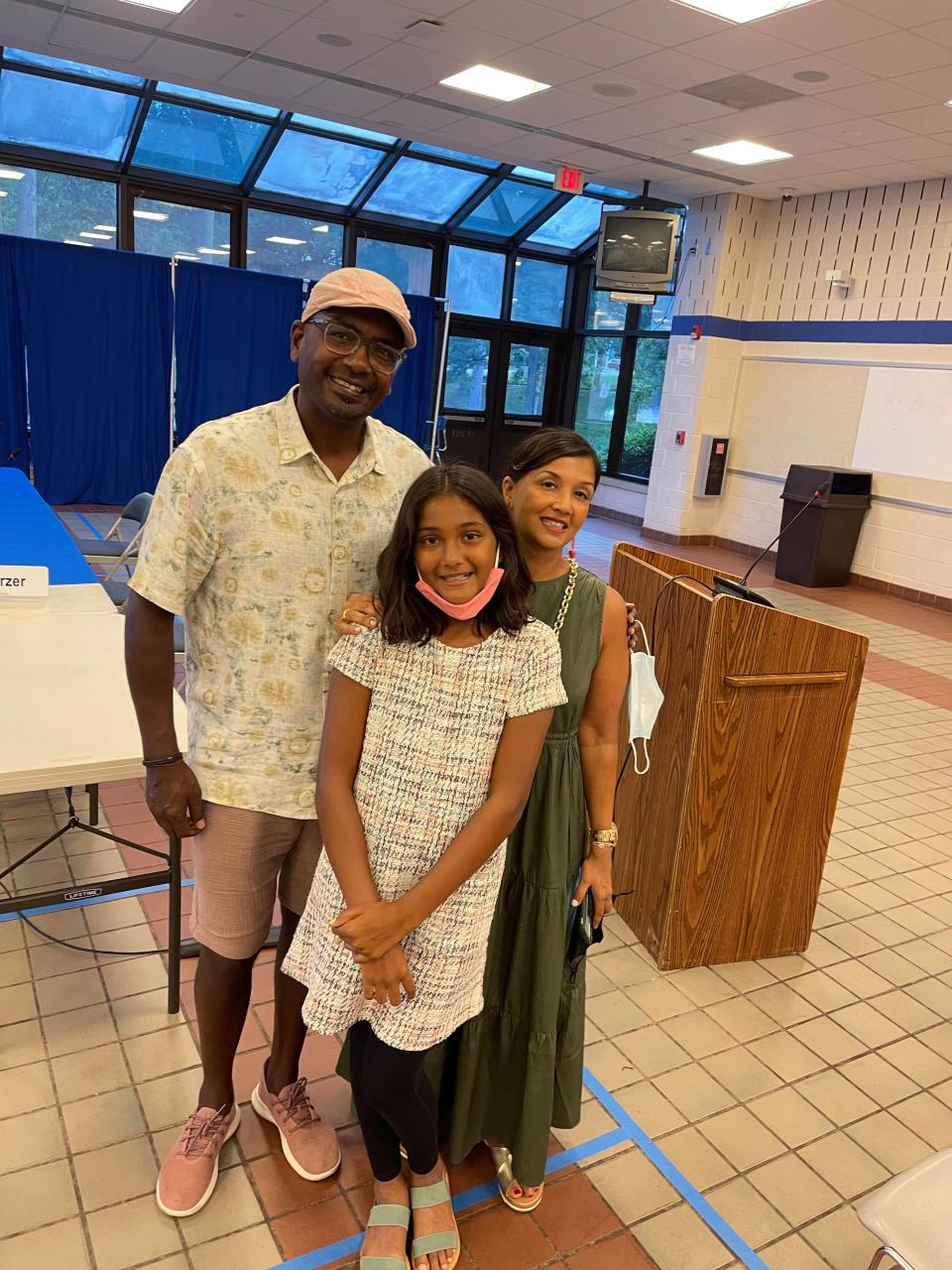

Khan said that although his hometown of Levittown has become more accepting of Bangladeshis, as his uncle and other family members moved there, he and his wife, Neha, still could not imagine it as a place to raise their daughter Laila, who's now 13.

"That's one of the reasons we moved to Montclair. We moved when my daughter was born, and I didn't want to raise her in an environment where she was not proud of who she was," said Khan, who lived in Guttenberg when Laila was born.

His daughter has embraced her parents' Hindu and Muslim faiths. In 2021, she convinced the Montclair school district to add the Muslim holiday Eid al-Fitr to the school calendar after leading a petition drive that gathered over 2,000 signatures.

"For her to be able to do that when I was hiding from all that 40 years ago, right now I get teary-eyed just talking about that, and I have goose bumps and chills down my back," Khan said.

Ramapo professor felt uncomfortable among friends

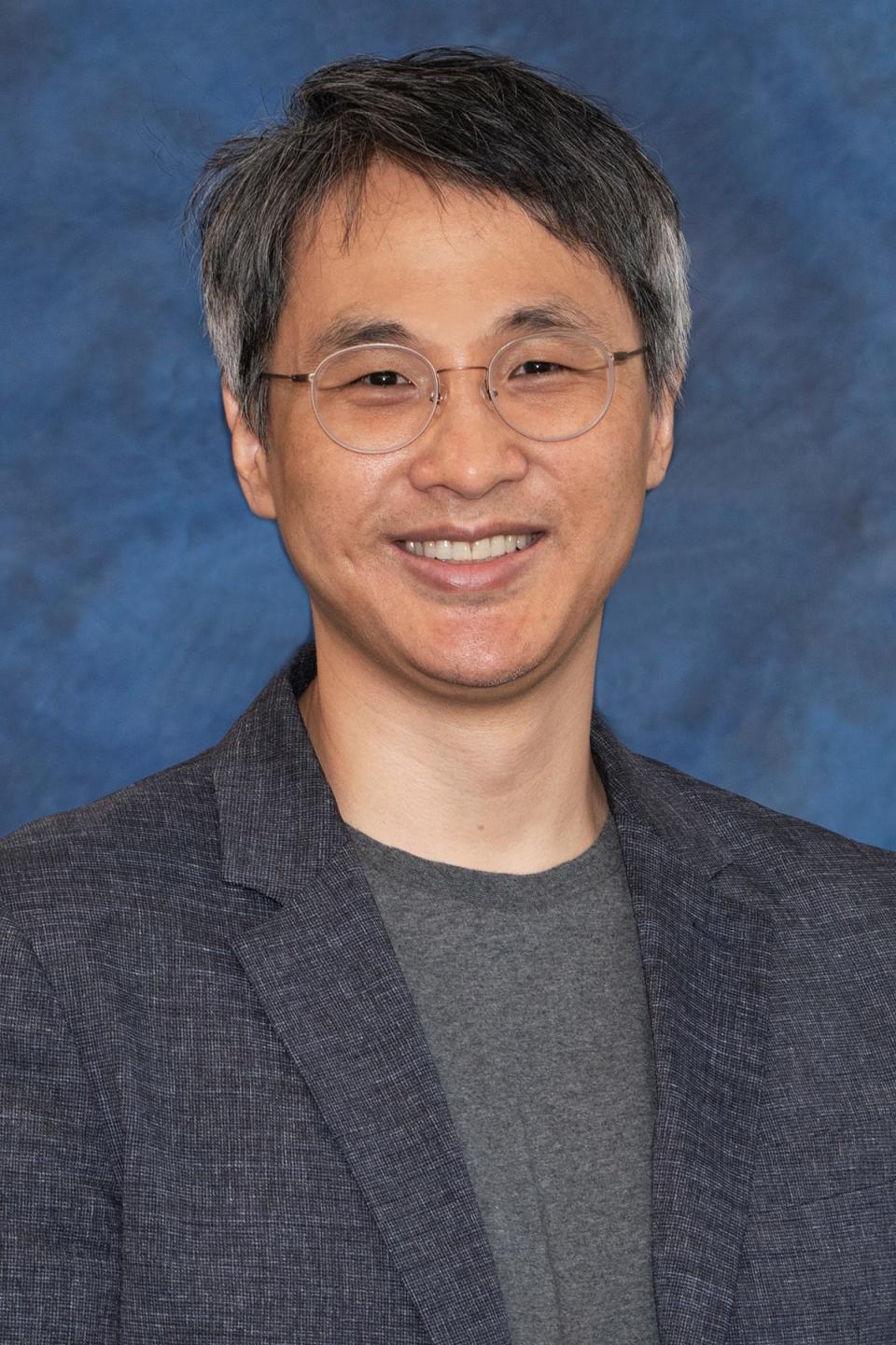

Growing up in Texas, David Oh did not want to invite friends to the home he shared with his Korean immigrant parents.

"There were things like taking off our shoes when we entered the house that they found unusual. I would have to explain, and it was uncomfortable," said Oh, who is now a professor of communication arts at Ramapo College in Mahwah. "Some of them would remark on the smell of kimchi. I didn't like having those remarks about something that we eat daily. It felt embarrassing and felt a little bit hurtful."

Oh was born in South Korea and came to the United States as an infant. His family lived in a predominantly white suburb in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

"One of the things I think that maybe is a little distinctive about Asian Americans is that many of us grow up in white, suburban neighborhoods. And growing up in white, suburban neighborhoods and practicing cultural identity in front of friends can make us feel even more outside of the mainstream and less accepted," Oh observed.

The 48-year-old recalled how the disdain of his friends toward his culture extended to how they viewed his family members.

"To their eyes, I suppose, my paternal grandmother was a little odd, and so they would make comments of how weird she was," Oh said. The professor also observed that he felt uncomfortable because his parents were not as expressive as the parents of white friends.

He said he has never fully overcome the childhood ridicule.

"As I have gotten older, I've been more willing to assert my cultural identity ... because I wanted to take space and want people to think about it," Oh said. "But it doesn't ever become not uncomfortable. I don't dress up in traditional Korean clothing to go to school to celebrate big Korean holidays. I don't just bring up in conversation things that are related to my identity as a Korean American unless it's germane in some way."

Jackson mom 'didn't want to be different'

Mindie Sobrinski of Jackson Township looks back at kindergarten as the time when she decided to not to make her Taiwanese background so pronounced.

"I like to say I assimilated a little too hard. My parents were born in Taiwan, so a lot of the cultural things that we did or even just foods [we ate] were strange to everybody, and I was really super shy when I was younger," Sobrinski said. "I would bring in food when I was in kindergarten and people would keep asking me about it, and I got really weirded out and scared and it was just awkward. I was embarrassed, so I never brought that stuff in."

In first grade, her language skills made her a curiosity, but she didn't like standing out.

"When people found out that I can speak a different language, they constantly asked me, 'How you say this?' How you say this?' And that was only in first grade," said Sobrinski, who speaks Mandarin. "I don't think they were doing it out of malice or anything, but just because I was getting that much attention, it was different. And I didn't want to be different."

Sobrinski, 39, lives with her husband and two children and teaches at Monmouth Regional High School. Her parents immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in 1980.

As she grew older, she said, she hid her identity by separating her school life from her personal life.

"I pretty much had two lives growing up: my school life, or my quote-unquote white person life, and my Asian life," Sobrinski said. "I went to Chinese school on Saturdays and Sundays and did Chinese dance all growing up. But I didn't really let those two worlds collide."

She added, "Just because I never really felt proud of who I was and where I came from, I felt being in this world, I needed to blend in and assimilate as much as possible to get to where I needed to go."

Pop quiz: 20 facts to know for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

Sobrinski grew more comfortable with her heritage in adulthood due in part to being a parent.

"With my children, I do have regrets of not teaching Mandarin as much. They speak a little bit," she said. "Now that I'm a little more comfortable in who I am, and being 39, I feel like I realize the need to embrace that part of myself and to teach my children cultural things like the foods and the language."

Seeing a more inclusive future

Despite his struggles, Khan sees a future in which Asian Americans can be proud of their culture, rather than hide it. He cites advances like the New Jersey law that requires schools to teach about Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage, as well as the growth of groups like AAPI Montclair, with which Khan is involved.

“There’s lots of work to do. But with organizations like AAPI Montclair leading the way, it continues to become easier,” Khan said. “Having Asian American studies be a part of the school curriculum so children can start to engage and learn about us and our contributions will further make it easier.”

Sobrinski said she believes that it's becoming easier for Asian Americans now to connect to their backgrounds.

"I feel that in the future for all of our children ... it will actually be easier and more welcomed for them to embrace their own culture and heritage because there are resources that they can go to," she said.

Ricardo Kaulessar covers race, immigration, and culture for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to the most important news from your local community, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kaulessar@northjersey.com

Twitter: @ricardokaul

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Why Asian Americans say they hid their heritage to survive suburbs