Why neglected governors' races are more important than you think

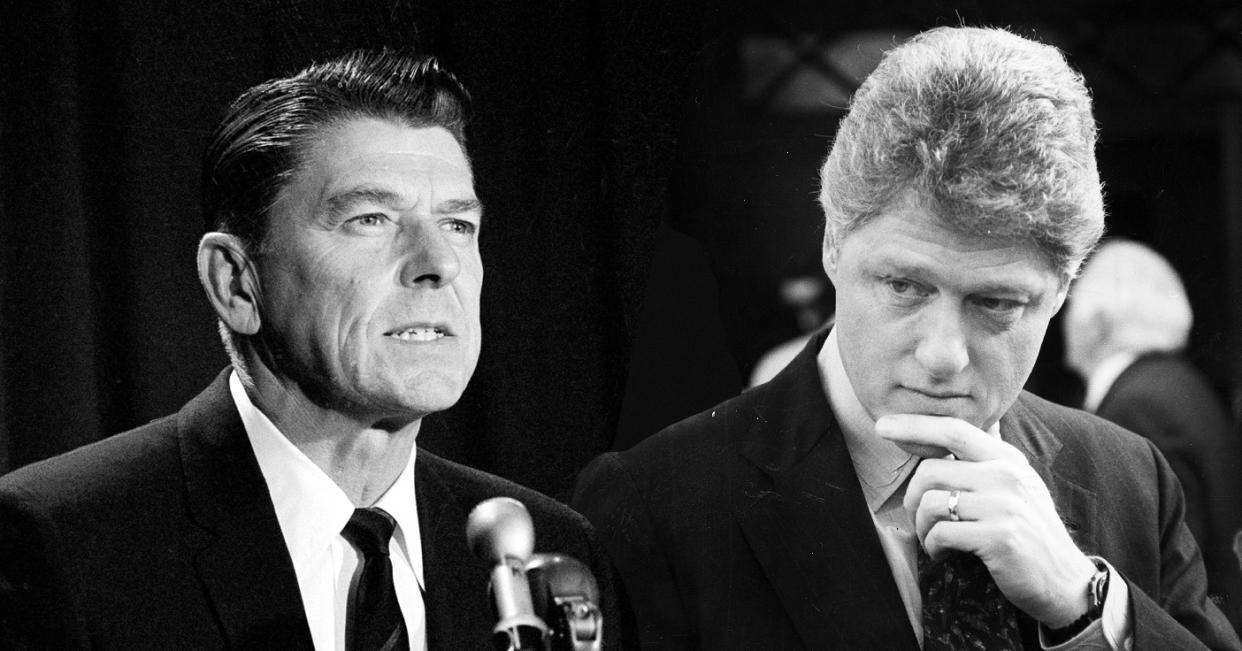

WASHINGTON — If you want to live in the White House, first try the governor’s mansion. Seventeen times, a state governor has become president of the United States. Ronald Reagan’s stint in Sacramento launched his national political career. Bill Clinton spent nearly 12 years as governor of Arkansas.

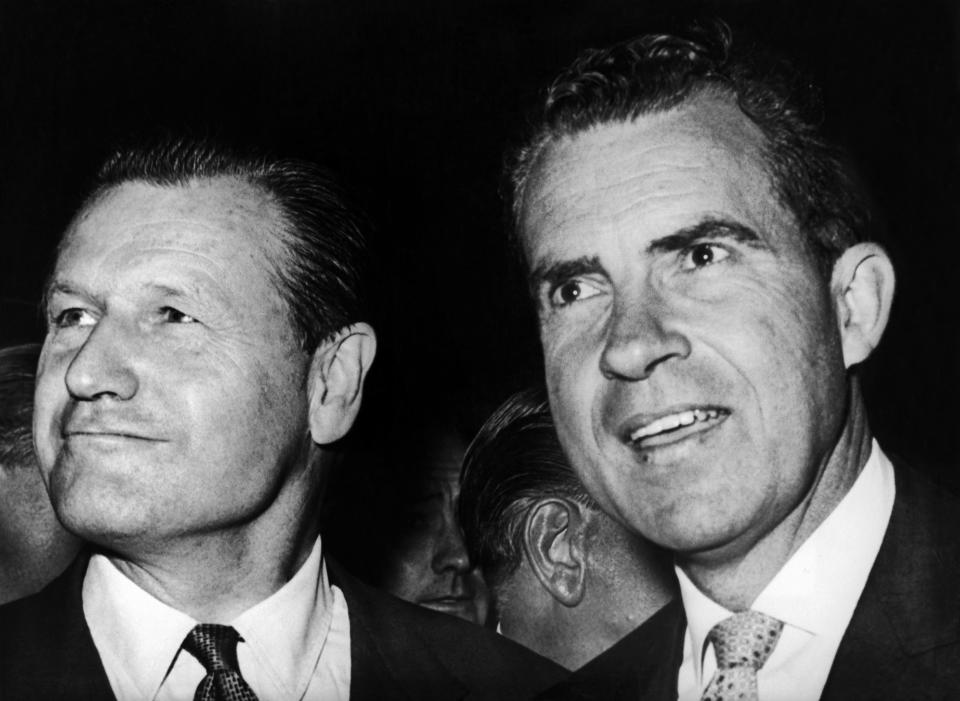

Though perhaps not as prominent as a seat in the U.S. Senate, a governorship is the most popular means of ascending to the presidency (albeit narrowly: 16 senators have become president). It is an equally popular means to the vice presidency — a title held by, among others, longtime New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and the office’s current occupant, former Indiana Gov. Mike Pence.

But as much of the nation focuses on what may be the most consequential congressional election in modern history, candidates for governor have largely been relegated by the media to second-tier status compared with their peers running for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

“It’s a natural inclination to focus on the national scene,” explains Whit Ayres, a Republican pollster who believes that governors’ races are undercovered because members of the media are “overwhelmingly located in Washington and New York,” where they are likely to become familiar with senators and representatives seeking higher office. Governors, meanwhile, are largely bound to their state capitals. That could mean spending their most of their time in Tallahassee — or Juneau.

In all, the 36 gubernatorial races that will be decided on Nov. 6 could either add local strength to a so-called blue wave in Washington or — should Republicans prevail in states like Nevada and Georgia — provide a state-based bulwark against a liberal takeover in Washington.

The scope of that takeover has captured the enthusiasm of both President Trump’s most spirited supporters and those who want impeachment proceedings to begin the moment the 116th Congress is gaveled into session. Pundits have issued a daily stream of projections about who will win the House (Democrats, probably) and the Senate (Republicans, almost certainly). In the midst of these furious prognostications, the question of who will occupy governors’ mansions has largely failed to capture the public imagination.

The exceptions are in Florida and Georgia, where the young progressives Andrew Gillum and Stacey Abrams are both seeking to become the first African-American governors in their states. But those are only two of three dozen governors’ races that will be decided in less than two weeks.

A few of the others are predictable because they are taking place in states where voter registration is tilted heavily in favor of one party: Democratic candidate Gavin Newsom is all but certain to prevail in California, while Republican candidate Brad Little has little to worry about in Idaho. According to Cook Political Report, 14 states are either certain or likely to elect a Republican governor, while 10 states are reliably predicted to choose a Democratic chief executive.

That leaves 12 governors’ races that remain unsettled — and perhaps as important as, if not more so than, any of the high-profile battles for Capitol Hill. Notably, some of the contested gubernatorial seats are in the Midwest, where states that had long been under full Republican control (meaning that they held both chambers of the state legislature and the governorship) are seeing strong Democratic challengers. In Kansas, for example, Democratic candidate Laura Kelly is tied with her Republican competitor, close Trump associate Kris Kobach, according to polling by political site FiveThirtyEight. And in the red redoubt that is Oklahoma, Democrat Drew Edmondson is within 7 points of Republican Kevin Stitt. Trump beat Hillary Clinton there by 36 points in 2016, carrying all 82 counties in the Sooner State.

“You can imagine 10 to 12” of the 33 gubernatorial seats currently held by the GOP going to Democrats, says Navin Nayak, executive director of CAP Action at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington. The notion that people are disengaged from gubernatorial races, he says, is nothing but a “Beltway mindset” that doesn’t reflect the reality outside Washington. “There’s a ton of energy and interest around governors’ races,” Nayak says. “Look at what happened in Virginia last year,” he added, referring to Democratic Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam’s unlikely victory over Ed Gillespie, an establishment Republican who had taken on some of the trappings of Trumpism.

Republicans, meanwhile, “are in strong position to pick up the Alaska governorship,” says Jon Thompson, communications director for the Republican Governors Association. Thompson adds that Republicans “remain competitive in numerous other contests that could be a net pickup for Republicans, including Oregon, Connecticut, Colorado and Rhode Island.” He discounts notions of a blue wave, predicting that Republicans “will still hold a large majority of governorships after Election Day.”

Democrats hope to reverse the tea-party-fueled cataclysm of 2010, which saw the Republicans win six governors’ mansions. That election, as well as elections that followed, allowed Republicans to make steady gains in statehouses. Between 2010 and 2015, Republicans won some 900 state legislative seats, the result of a coherent strategy to galvanize the conservative base. After the 2016 election, Republicans could boast 24 states in which both the entire statehouse and the governor’s mansion were under GOP control. Democrats had only six such states.

Ayres, the Republican consultant, calls being governor “the best political job in America,” where a genuinely committed leader can get much more done than they could in Washington, where partisan scrums often dominate the day’s work. Ayres got his start working for Lamar Alexander, governor of Tennessee in the early 1980s, and Carroll Campbell, who was governor of South Carolina in the 1980s and 1990s. Ayres recalls how both men, whom he calls his “mentors,” were immensely popular for focusing on education and bringing automotive jobs to de-industrialized stretches of the South.

“Governors are also important,” Ayres adds, “because they actually make life-and-death decisions — unlike almost all other offices.” For example, they have the power to commute death sentences or refuse to do so. George W. Bush, as governor of Texas, was known for what the New York Times called a “busy death chamber.” They also decide when to order evacuations for natural disasters, and how to coordinate recovery efforts with federal emergency response officials. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie was widely lauded for embracing President Barack Obama in responding to the devastation caused by Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

And it was up to governors whether to accept the Medicaid expansions provided for under the Affordable Care Act. Among Republican governors who refused the aid, citing federal overreach, were Paul LePage of Maine and Scott Walker of Wisconsin. Walker, who is running for reelection, has been losing ground to his Democratic challenger, Tony Evers, a sexagenarian educational official described by the Associated Press as “bland.” Governors will oversee the redrawing of congressional districts that will follow the 2020 census. Partisan redistricting — gerrymandering — by Republican governors who had been elected in 2010 allowed the GOP to increase its hold over the House of Representatives.

A new conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court will likely allow states to make their own determinations about how much access to provide to abortion providers. The contentious confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh — who gives conservatives the crucial fifth vote on the high court — has allowed Democratic gubernatorial candidates to argue that they will provide a state-based resistance to any efforts by the Supreme Court to challenge the legality of abortion. In Iowa, Democratic candidate Fred Hubbell has declared himself “an unabashed supporter of Roe v. Wade,” while Janet Mills, the Democratic candidate in Maine, recently tweeted, “I will always defend women’s reproductive health and a [woman’s] right to choose.”

While Democrats across the nation have been enthralled by Abrams and Gillum, the candidates in Georgia and Florida, the GOP has not managed to engender the same excitement. No Republican gubernatorial candidate seems to have similarly energized voters. One Republican operative in Washington — who requested anonymity in order to speak freely — lamented that the party establishment had done a poor job of selecting candidates. He also said endorsements by Trump sometimes proved unhelpful.

In Florida, for example, Trump endorsed Ron DeSantis, a congressman who made frequent appearances on Fox News, the president’s favored source of information. The endorsement allowed DeSantis to win the Republican primary, but he has fared poorly as a general-election candidate, mired from the start of the campaign in accusations of racism. That has prevented DeSantis from making gains against Gillum, who as mayor of Tallahassee has faced allegations of corruption.

Winning the governorship of a state like Florida could easily catapult a politician to national prominence, especially if he or she proves a capable chief executive. But, as Ayres cautions, “We need to leave room in our thinking for governors we’ve never heard of” — one who may emerge not because of the campaign they ran to get to the governor’s mansion but because of the job they did once they got there. That’s because, he says, states are “incubators” for ideas that could gain attention nationwide — for example, when Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney drastically expanded health care coverage in the state in 2006. That increased his national profile, and he ran for the presidency in 2012, a race he lost to Obama, the incumbent.

And then there is Jimmy Carter, who in 1970 was elected governor of Georgia on a liberal, forward-looking agenda. At the time, he was a virtually unknown 47-year-old. Six years later, he was elected again — this time to the presidency of the United States.

_____

Read more Yahoo News midterms coverage:

Red-tide awakening: How Florida’s environmental woes could hurt Rick Scott

‘Outside agitators’ phrase resurfaces in Georgia governor’s race

Menendez race pits ethical concerns against party loyalty, and loyalty is winning

Portrait of a moderate district: NJ-11 leans R, but the race leans D

In Senate race, GOP Rep. Blackburn accuses her opponent of being a Democrat

Photos: Suspicious packages sent to top Democrats, CNN and others