Neil Armstrong's Words—No, Not Those Words—Have Stuck With Me All These Years

He stood looking through the lace/At the face on the conquered moon -- Joni Mitchell

The Vietnam War went on for another three bloody years after Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon; twenty-thousand more Americans would die over that span of time, and God alone knows how many Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians. Senator Edward Kennedy drove his car into a pond on an island off Massachusetts and a woman named Mary Jo Kopechne died in it. York, Pennsylvania blew up in a race riot. The members of Charles Manson's cult slaughtered seven people in and around Beverly Hills, California. Sectarian riots exploded in Northern Ireland, leading to the arrival of British troops and almost 30 years of unremitting paramilitary—and military—violence. Woodstock and Altamont both happened, the Austerlitz and Waterloo of the counterculture. Hurricane Camille killed 256 people in Louisiana and Mississippi. Muammar Gadhafi became the leader of Libya in a coup, Ho Chi Minh died, and the very first message was sent over something called ARPANET. Seymour Hersh broke the story of the My Lai massacre and Spiro Agnew fired his first salvo at the media. And, on November 12, 1969, Charles Conrad and Alan Bean became the third and fourth men to land on the moon.

The point is that history went on, blind, blundering, bloody, and stumbling, the way it always does. Apollo 11 did not stop history. In fact, looking back now over 50 years, it almost seems like an event outside of history. All of the moonflights do now. (Eugene Cernan is, for the moment, at least, as far as we know, the last human to walk on the moon. Win a beer at your local with that one.)

They were supposed to unite us, and they did. They were supposed to elevate our gaze beyond our differences and difficulties, and they did, for a while, anyway. (By the flight of the unfortunate Apollo 13, the networks weren't even carrying the live broadcasts from space any more.) But, in retrospect, they have been said to have redeemed us from that troubled time, and that's putting far too much on them for the moonflights to carry even in memory. History went on without them. They exist now in that place outside of history where we keep things both remarkable and fragile, both hard reality and delicate myth, both the solid reality of a moon rock and the pure imagination needed to look up at a large white dot in the night sky and think, yeah, we should go there.

A long time ago, my father took me to some dinner at which the guest speaker was Sir Edmund Hillary who, with Tenzing Norkay, was the first man to reach the summit of Mount Everest. My father got his autograph for me on a plain white index card. I do not collect autographs and, as far as I know, Hillary's was the only one I ever had, and it certainly was the only one I kept, and I kept it for one reason and one reason only—I wanted to get Neil Armstrong's autograph on the card next to Hillary's. Then I would frame it and hang it on my wall forever. I never did it. Armstrong was a hard find and he died in 2012. I don't know where the index card is any more.

"The land was first seen by a sailor called Rodrigo de Triana..."-- Entry for October 11, 1492. The Journals of Christopher Columbus

Good thing for all concerned, I guess, that the moon was unoccupied. Human discovery and exploration has been a brutal process on this planet, especially upon the indigenous people who were "discovered" and their land which was "explored." There were no indigenous moonmen to slaughter, no great forests to burn down, no temples to ransack on the promise of gold. There was gray dust and rocks and craters and a kind of blessed lifelessness that offered nothing to the venal and vicious elements in the human condition. (Even Everest never offered that. The Sherpas were treated badly and, now, they have to send expeditions up the slopes, not simply because they're there, but because so much garbage is.) There was nothing to wreck or pillage. There was only a lot of there there. If this was conquest, it was conquest over ourselves, and not over somebody else's riches and somebody else's land. And if the conquest was not complete—and it wasn't, because of all the parts of ourselves we couldn't conquer back here—it was undeniably real.

I mean, hey, it was right there on television, in the blackest black and the whitest white anybody ever had seen. In my growing up, there were three unforgettable moments on television. Two of them happened the same awful November weekend in 1963—the first bulletins about a shooting in Dallas, and the completely surreal murder of Lee Harvey Oswald right there on live TV. The third was the moment Neil Armstrong said, from a quarter-million miles away in the sky, "OK, I'm gonna step off the LEM now." That has stayed with me even longer than his more famous—and famously botched—quote about small steps and giant leaps.

OK, I'm gonna step off the LEM now.

Simple. Prosaic, even. Something like the things you say when you're going to the store, or heading outside to mow the lawn, or taking the dog for a walk.

OK, I'm gonna step off the LEM now.

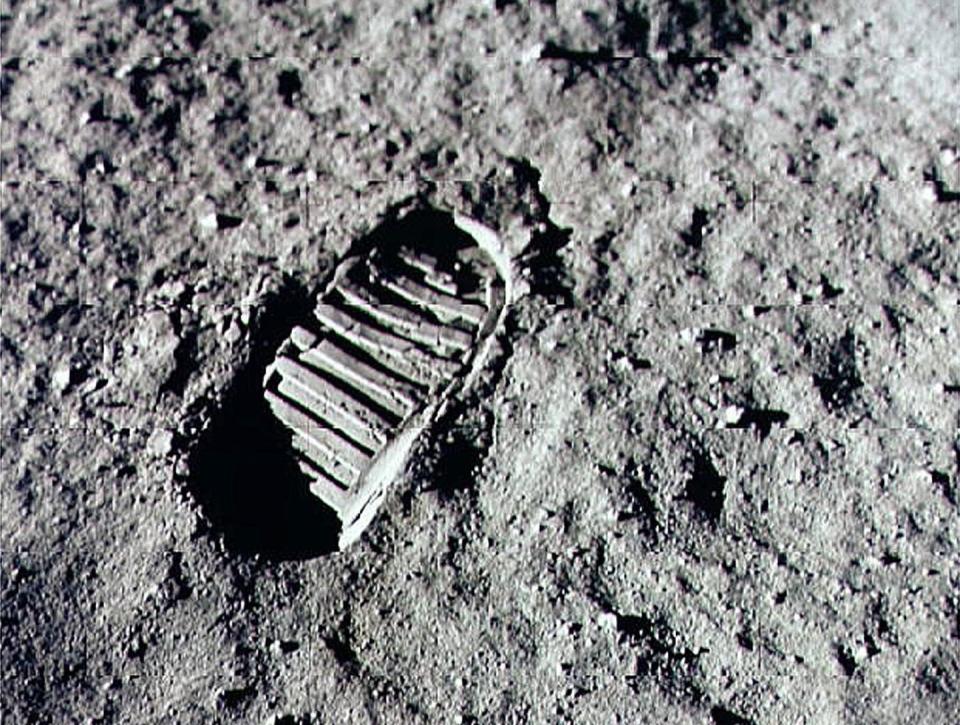

And, assuming you don't float away, when your foot comes down and leaves its imprint in the dust where no footprint ever has been, everything will be different. It won't even matter if you don't get the famous quote quite right. The words mattered far less than the place where you said them. You could have stumbled right then and fallen, ass over teakettle, in a cloud of virgin dust. But you didn't. You stepped off the LEM and everything changed in that place outside history, where we keep things both remarkable and fragile, both hard reality and delicate myth, both the solid reality of a moon rock and the pure imagination needed to look up at a large white dot in the night sky and think, yeah, we should go there. And we by God did.

You Might Also Like