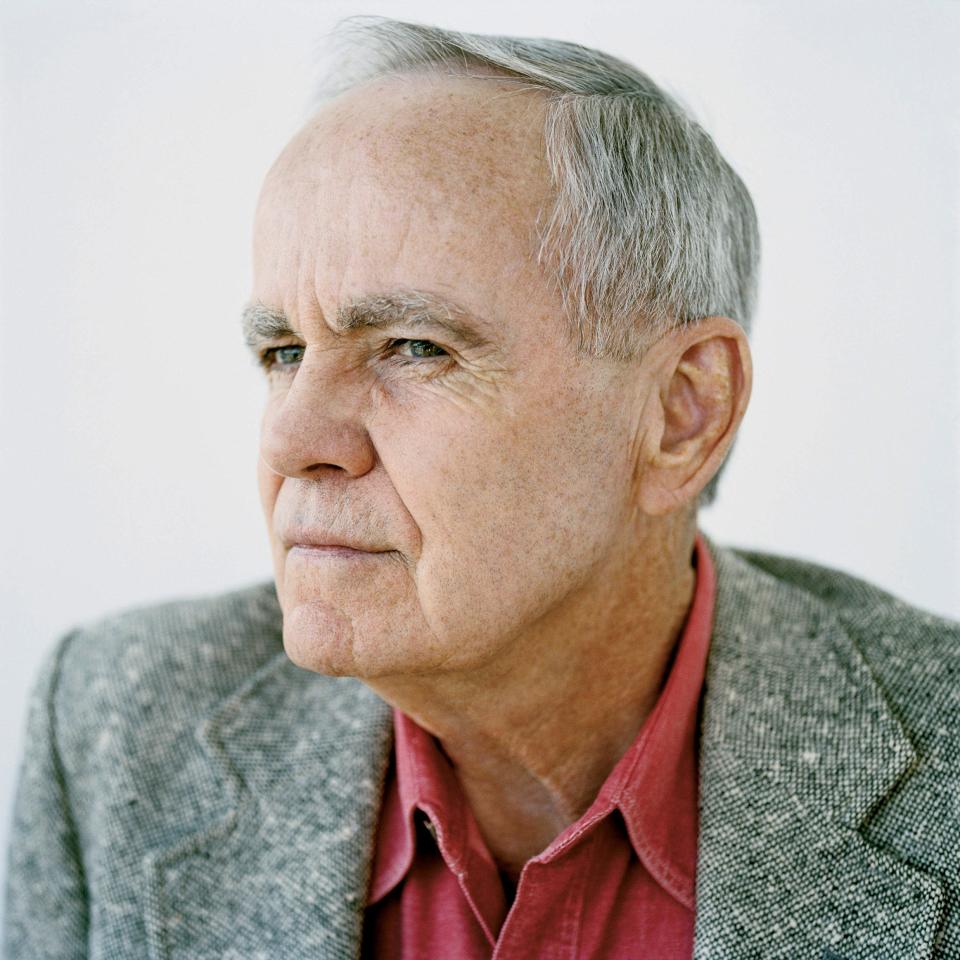

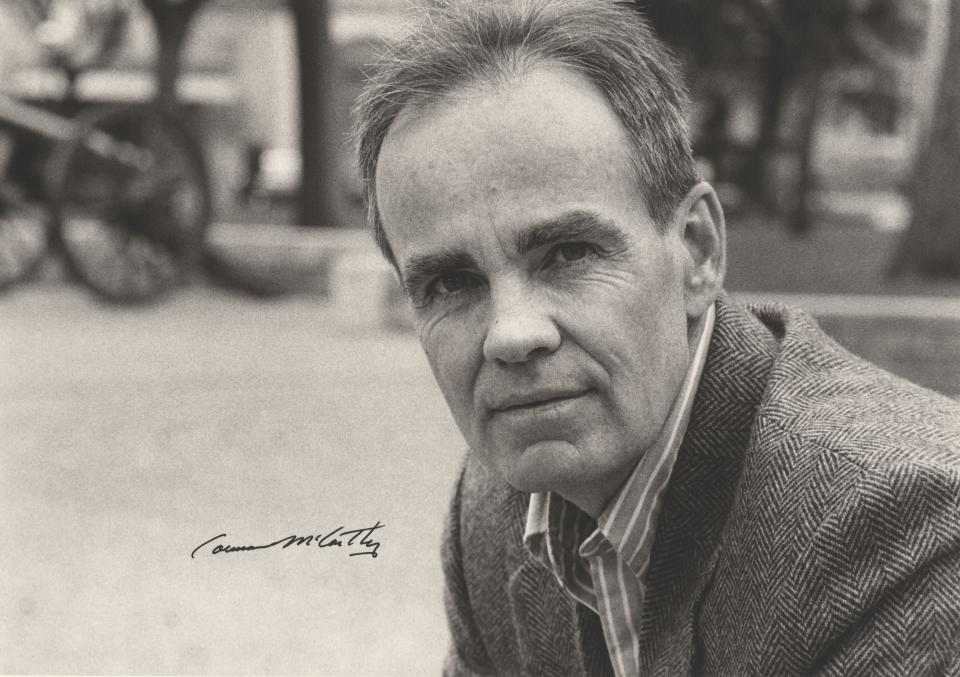

‘We will never see his like again’: Remembering Cormac McCarthy beyond his bleak novels

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Known for such books as “The Road,” “No Country for Old Men” and “All the Pretty Horses,” author Cormac McCarthy was praised - and criticized - for works that were brutally violent, morally ambiguous and bleak. Even so, McCarthy left an undeniable legacy in literature and in Knoxville.

The Pulitzer Prize winner, who had close ties to Knoxville in his personal history and his books, died this week at 89, just over a month shy of his 90th birthday.

“He's clearly a pretty influential writer,” Eric Dawson of Knox County’s McClung Historical Collection told Knox News last year. “You can't imitate him because it's so obvious, his language and style of prose is – well, for a lot of people, it's difficult."

“When I walk the streets of the Scruffy City, images from the novel ‘Suttree’ (by McCarthy) and the 1950s constantly arise in my mind,” Knoxville author William Walker told Knox News in an email on June 13, the day McCarthy's death was announced.

“McCarthy captured a time that is now lost, and we will never see his like again,” Walker continued, calling the late author “the greatest Knoxville writer of all times.”

Acclaimed writer Stephen King agreed, writing in a tribute on Twitter that McCarthy “may be the greatest American novelist of my time."

“He was full of years and created a fine body of work,” King continued.

Giving space to the little wonders of humanity

McCarthy, a somewhat reclusive writer, authored 12 novels. His first, “The Orchard Keeper,” was published in 1965, and his final two books were released in late 2022. He drew heavy inspiration from the South and his time in East Tennessee for his Southern gothic and neo-Western stories.

Post-apocalyptic scenes, graphic depictions of violence and a unique writing style set him apart from other writers. Every McCarthy release was “a haunted, tortured, dark and deeply sad literary event” – of the best kind, of course – USA TODAY wrote in a review for his book “The Passenger” in 2022.

But exactly what was the point? Why was McCarthy fixated on the bleak and grim?

“I think in his work he uses violence to boil down the necessity of morality and thoughtfulness and care,” Zachary Turpin, professor of American literature at the University of Idaho, shared with Knox News last year.

“It really felt like the violence was beside the point, that all that awfulness helps distill the wonders of the little moments of humanity,” Turpin said. “It's not because he loves the gore or because it's all that there is. I think that he shows life and humanity its worth, to show that there's still something behind all that that's good.”

A literary legacy built on style and purpose

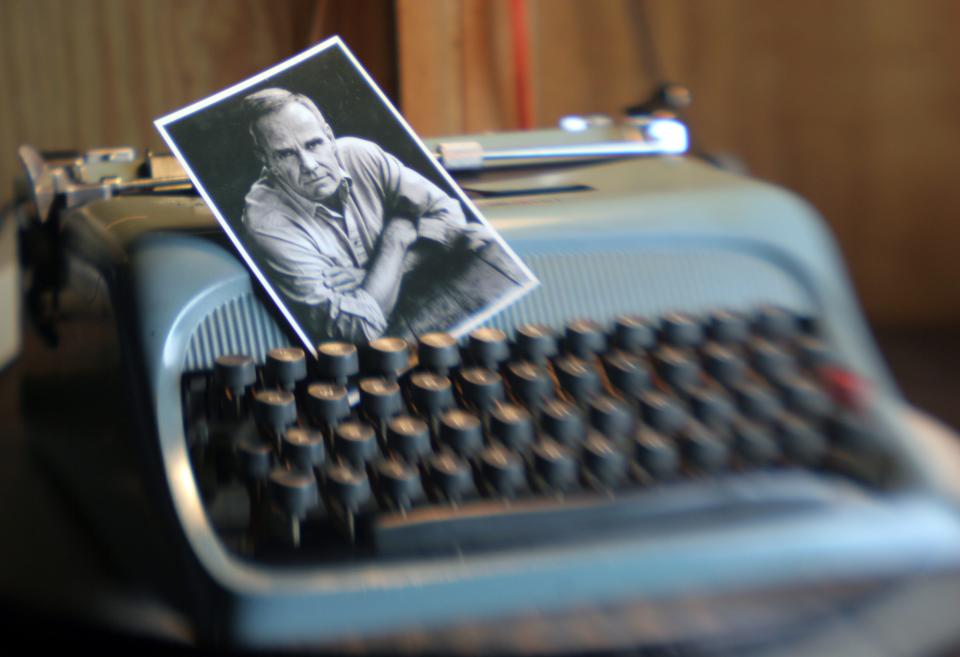

Along with violent graphic detail, McCarthy was known for his writing style and cadence. He wrote in detailed, declarative sentences, often sparsely punctuated and void of attribution to dialogue. Turpin suggested this unique style is a pillar of McCarthy’s lasting literary influence.

“It would be tempting to say that he's had a big influence on the way that literature has gotten, not just the way it reads, but like what people write about or their stance toward humanity or art,” Turpin said. “It does sometimes feel like he is both, at the head of a tradition that's ongoing stylistically and also holding a torch that not a lot of people are trying to take up."

Forcing readers who can get past the gore to think critically about morality and humanity was McCarthy’s impact from Dawson’s perspective.

“If you read enough of those works you do get the sense of somebody who is very much questioning, very intellectually curious, is not afraid to ask the big questions,” Dawson said. “He asks the big questions, I think, about existence, about what we're doing here and how people interact with one another and treat one another.”

It’s what makes McCarthy’s work consistently relevant. Dawson recalled how “Suttree,” McCarthy's novel released in 1979 and set in Knoxville, asks the big questions and mirrors issues of today.

“I think ‘Suttree’ is a particularly interesting book because a lot of what he's talking about – again it’s written in ‘79 and takes place in early '50s – are things we're still dealing with now, such as urban renewal, police violence, homeless. It's these things that are in the headlines now.”

McCarthy’s life in Knoxville and East Tennessee

McCarthy’s first four novels were set in East Tennessee. “Suttree,” a semi-autographical story, was set in Knoxville, where McCarthy grew up. The main character in his fifth book, “Blood Meridian,” is a teenager from Tennessee.

“He obviously had a real interest in the rural area around here,” Dawson said. “Very few books take place in any city that go into detail about the city as much as ‘Suttree’ does.”

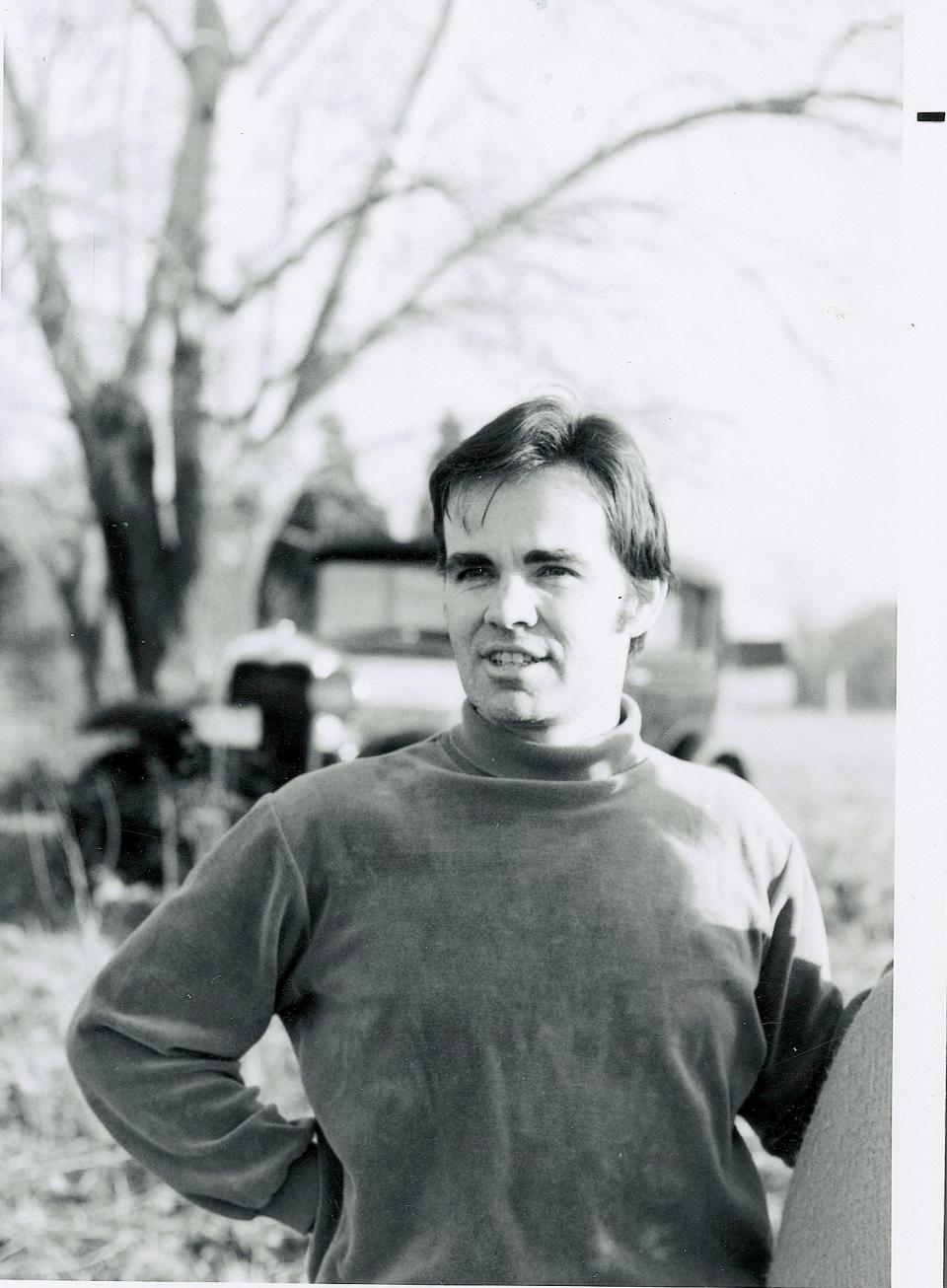

Born Charles McCarthy Jr. on July 20, 1933, in Rhode Island, McCarthy moved to Knoxville with his family when he was around 4 years old in 1937. His father worked as a general counsel for the Tennessee Valley Authority. They briefly lived in Sequoyah Hills and then moved to a house on Martin Mill Pike, which burned down in 2009.

McCarthy went to Knoxville Catholic High School. He showed an early interest in drama, appearing in a local film and then auditioning for Clarence Brown's 1946 MGM film, "The Yearling," but did not get the part, according to Dawson.

It’s possible he was sort of a rowdy rebel during his Knoxville days. Dawson shared a recently resurfaced story that when McCarthy was 13 or 14 years old, he and one of his friends were playing with guns and the future author accidently shot himself in the leg.

And then when he attended the University of Tennessee for one year in the early 1950s, he either “dropped out or was kicked out, depending on your sources,” reported News-Sentinel writer Don Williams in 1990. McCarthy returned to UT after serving in the Air Force, but ultimately chose to leave to focus on his writing career.

It’s unclear why McCarthy dropped Charles and began using Cormac, but Dawson noted the moniker is a traditional Irish name.

McCarthy lived in rural Sevier County and Blount County in the 1960s and ‘70s, before moving West and ultimately settling in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he died. However, East Tennessee remained an inspiration to the author.

In his highly anticipated literary return in 2022, “The Passenger" prominently featured Knoxville, Clinton and Wartburg. The main character's father even works in Oak Ridge.

Remembering McCarthy

McCarthy introduced Knoxville to the world through his books. And the city has returned the adoration. Suttree Landing Park on the Tennessee River in downtown Knoxville is an homage to the book and its lead character. Suttree's High Gravity Tavern and Harrogate's Lounge are also references to the book.

“Great artists don't come from nowhere. It takes practice. It takes dedication it takes willingness or even a readiness to fail or to throw out what doesn't work and to self-analyze,” Turpin said when reflecting on McCarthy’s career.

McCarthy received many awards during his career, including the William Faulkner Foundation Award (“The Orchard Keeper”), MacArthur Fellowship, National Book Award for fiction (“All the Pretty Horses”) and a Pulitzer Prize for “The Road,” which was also an Oprah Winfrey book club selection.

The 2007 film adaptation of “No Country for Old Men” won four Academy Awards, including best picture.

Devarrick Turner is a trending news reporter. Email devarrick.turner@knoxnews.com. Twitter @dturner1208.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Remembering Cormac McCarthy’s legacy and early life in East Tennessee