‘Never been a suburb of Charlotte’: Towns of Huntersville, Mooresville turn 150

The reason the span of a few days in a single year brought enormous change to the area north of Charlotte had little to do with anyone wanting to create a new identity or a fresh start.

As with many things, it came down to money.

And the villages that would become Huntersville and Mooresville needed more of it 150 years ago if they were going to survive.

“Villages do not have the same rights and powers that towns have,” said Andy Poore, Mooresville Public Library local history and archives expert. “They can’t levy certain taxes.”

And as both villages were struggling to rebuild — along with the rest of the South — just seven years after the end of the Civil War, leaders realized that taxes would solve a lot of problems. The money could provide infrastructure and services, along with the ability to create incentives to make the towns grow.

“And that’s why they incorporated, because then that gave the town more power to collect taxes, to offer incentives to create businesses, things of that nature,” Poore said.

So on Feb. 28, 1873, a little village north of Charlotte called Craighead incorporated and renamed itself Huntersville in honor of major landowner and cotton farmer Robert Boston Hunter.

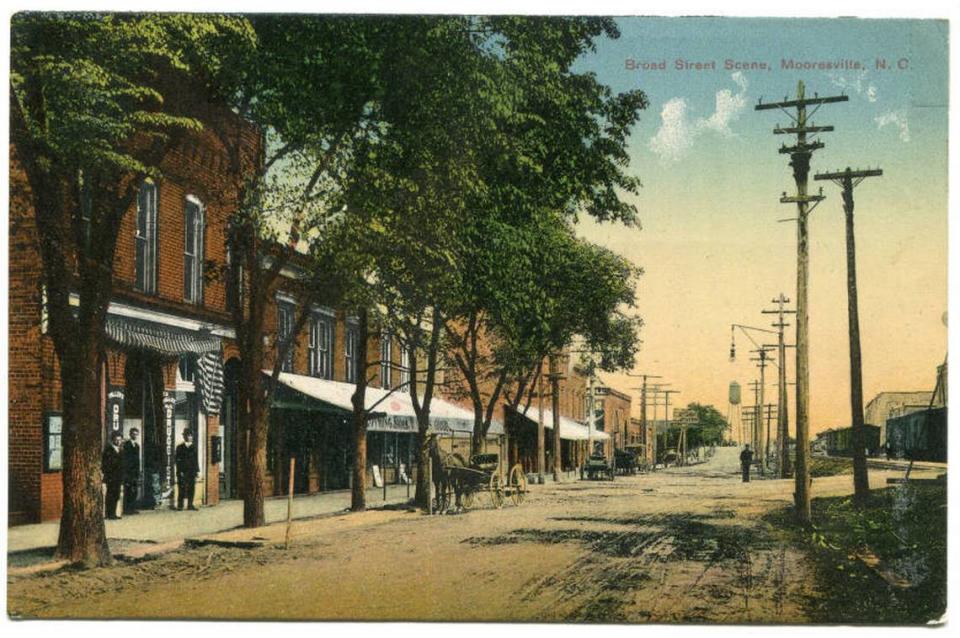

Less than a week later, on March 3, 1873, the village of Moore did the same, incorporating and becoming the town of Mooresville. The population was 25 people.

And from that point on, Huntersville and Mooresville sought to forge their own identities. Both had connections to textile mills that gave them early economic boosts. But both began to chart their own paths as family-friendly communities where people could can both live and work.

Neither, though, has ever claimed to be just an offshoot of the bigger city to the south.

“We’ve never been a suburb of Charlotte,” longtime resident and former Huntersville mayor Sarah McAulay said. “You know, it offended me when people talked about it being a ‘bedroom community.’”

Said Poore: “Calling us a suburb of Charlotte is not accurate. I mean, yes, we’re close to Charlotte. But a lot of people who live here work here. That’s not really our identity. We are more than just a suburb.”

Here, then, is a brief look at how both towns started, what each has become in 150 years, and their visions for the future.

Huntersville: From farmland to family land

When Huntersville incorporated, it was 1-square mile. The railroad that ran through town connected Huntersville to nearby cities and made it easy to transport goods from the farmland that blanketed the countryside.

The boundary line between the town and the county ran straight through Sarah McAulay’s childhood home — which she still lives in today — on Gilead Road.

“If you went to the front door, on your right you were in the town,” said McAulay, now 83, “and on your left, you were in the county.”

Change occurred gradually, as farming and textile mills gradually gave way to simple business opportunities in nearby Charlotte.

By the mid-1940s, nearly every Huntersville family had at least one family member working in Charlotte at Duke Power, Southern Bell or one of the banks, according to McAulay. The downtown area had three grocery stores, banks and two car dealers. And Huntersville quickly was modernizing.

A newspaper article from 1950 said, “Huntersville … is currently in the spotlight as perhaps the only municipality in the United States whose every foot of streets is paved.”

McAulay first was elected as mayor of Huntersville in 1969, running for office over a zoning issue she didn’t agree with, and her four-term service combined with seven terms on the town board coincided with some of the greatest change in the town: Huntersville grew from that 1-square mile to 63-square miles now, via land annexation that continued through the 1980s and 1990s.

Although the land area of the town grew, the population stayed relatively steady for decades.

Catching up to a population explosion

When Melinda Bales moved to Huntersville in 1999, the town was in the midst of a population explosion. In 1995, Huntersville’s population was 5,000 people. By 2000, it was more than 20,000, quadrupling in five years.

Birkdale Village, the popular mixed-use development in Huntersville, opened in 2003 and spurred more growth, as did the opening of the Novant Health Huntersville Medical Center in 2004. Business parks tucked in alcoves of the town housed manufacturing and technical businesses. The town’s proximity to both Charlotte and Charlotte Douglas International Airport made it attractive to those who needed to travel or work nearby.

Now, about 61,000 people live in the town that Bales presides over as mayor. The town’s 2040 plan says that population is expected to grow to more than 106,000 in the next 17 years.

“The infrastructure we still are driving on, a lot of the infrastructure is the same,” Bales said. “So we’re playing catch-up. The future of Huntersville, it’s going to be very important that our infrastructure, we catch up on that.”

That means encouraging more development away from the “spine” of the town, along Interstate 77. More businesses and shopping opportunities where people live will help with current traffic gridlock, Bales said.

“That way folks out to the west don’t have to drive to the center of Huntersville for their shopping or to pick up a coffee or go to the dry cleaners’,” Bales said.

“That’s the lynchpin in all of it — managing the growth and managing it well, especially to the east and to the west.”

As Huntersville continues to grow, some of the affordability problems of Charlotte have crept in too. The median home value in 2018 was $283,300; Realtor.com lists the median sold price as $489,000 in February 2023.

The town recently formed an affordable housing task force to look for solutions.

“What I would consider our ‘workforce housing stock’ is no longer affordable,” Bales said. “So, what do we need to do to preempt that issue, ensuring that our nurses and our police and our fire(fighters) and our teachers and those people that keep Huntersville running, how can we make sure that there’s some affordable workforce housing options for them in the place that they work?”

Because that’s what Huntersville has become, Bales said, and what she wants it to continue to be.

“I would have to say we’re a family-friendly community that also provides opportunities for employment,” she said. “I don’t know how else to describe it.”

Mooresville: Textile mills to Race City USA

Mooresville, just over the Mecklenburg-Iredell County line, not only was founded in the same week as Huntersville, but it had much of the same early focus — on textile mills and its connection to neighboring cities via the railroad that came through town.

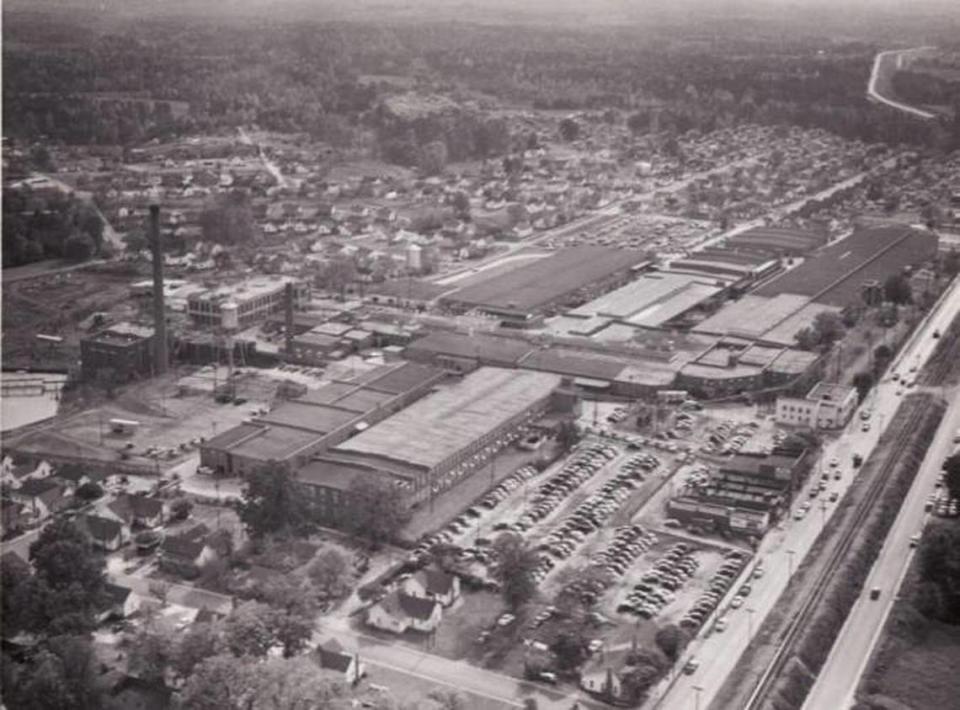

But Mooresville’s reliance on the mills lasted longer and was more woven into the fabric of the community, Poore said.

“We were starting to define ourselves not as this small village, but we were defining ourselves as a town,” Poore said. “We weren’t sending stuff to Charlotte and other mills. We had the mills to process cotton.”

Mooresville’s cotton mills were so successful that they received government contracts in World War II to make linens for the military and fabric that would be used to make parachutes, according to Poore.

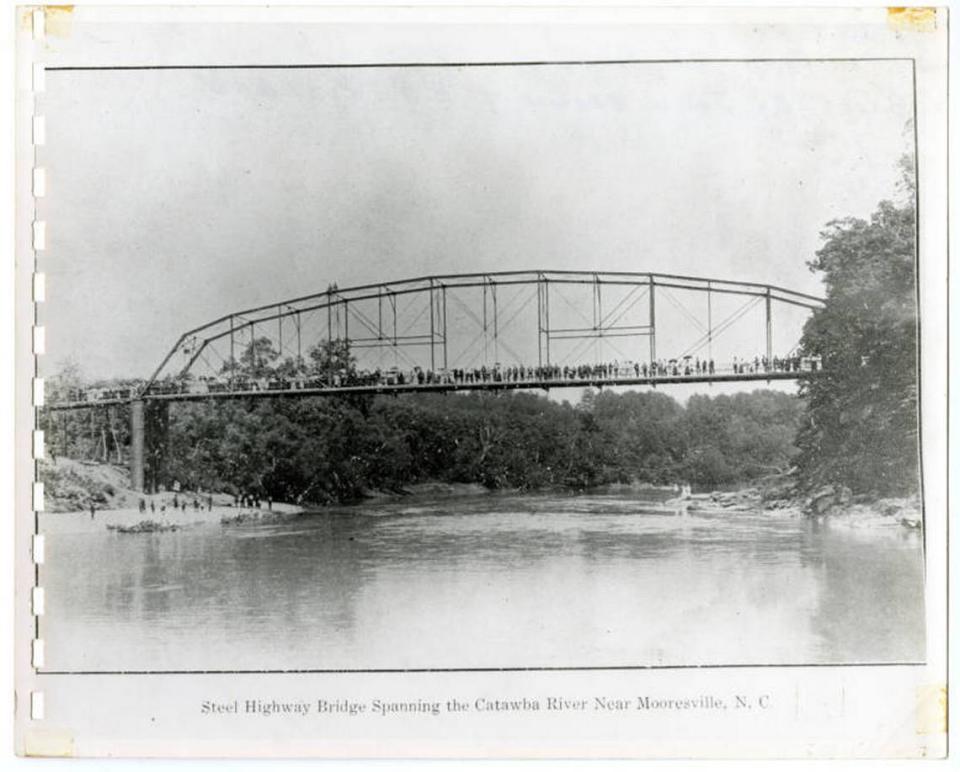

But one of the most defining moments in the town’s history came in 1959, when construction began to create Lake Norman. It took four years to build the dam on the Catawba River, and two years to fill the lake, but Mooresville’s new access to the water made an enormous impact. One newspaper reporter dubbed Mooresville “The Port City of Lake Norman.”

“I wish we still had that,” said Mooresville commissioner Bobby Compton of the moniker. “It gave us an identity, and we were small back then.”

In the 1990s, the town’s cotton mills began closing and Mooresville searched for a new industry to make its foundation. It settled on NASCAR.

“We had this labor pool of people who worked in the mills who worked with machines and did electrical work,” Poore said. “It made sense.”

Town officials worked with county and state representatives to build a business district and industrial park that would attract NASCAR teams with tax incentives. Several drivers and teams — notably, Team Penske — set up shops in the town and it dubbed itself “Race City USA.”

Redefining as a Tech Town?

Mooresville’s population has nearly doubled in the last two decades, rising from about 41,000 in 2000 to almost 79,000 in 2020.

By 2040, Mooresville expects nearly 100,000 to live in its town limits, according to the One Mooresville Comprehensive Plan.

Lowe’s established its headquarters in Mooresville in 2003, shifting the town’s identity a bit and providing a major economic boost. Town commissioner Compton thinks it’s vital to cultivate a whole new industry moving forward.

“Since we’ve lost the textile industry and because racing in the way our world has evolved (is changing), we’re starting to get into technology,” Compton said. “Our economic development partners are helping us to draw some technology-based industry to town.”

The town is developing a tech park off Langtree Road, and already has one national security firm with offices there.

“So we’re very heavy in attracting business and industry, but with an eye toward technology,” Compton said. “That’s just the way this world is now.”

But like its sesquicentennial neighbor to the south, Mooresville also is trying to manage its rapid growth efficiently so that adequate housing remains and traffic issues are minimized.

“We want people to not only work here with the businesses we obtain or want to come here, but we also want them to live here,” Compton said.

There’s a reason it has been attracting people to its town limits for 150 years.

“It’s home,” Compton said. “It’s security, it’s family, it’s love. I mean, I love this town and the people in it.”