‘Never told anything’: Family searches for answers after man dies at Leavenworth prison

Nearly two weeks after her son’s death in a Leavenworth federal prison, Tracie Washington still doesn’t know what happened to him.

Trenton Washington, 33, died on April 15 in a hospital after he was found unconscious in his cell the day before, according to a news release from the United States Penitentiary Leavenworth.

Multiple family members have called the prison every day since then. They want to know how a healthy 33-year-old father who was once a champion wrestler died within weeks of arriving at the federal prison.

So far, they’ve received no answers.

The family said they’ve called dozens of times, left voicemails for the prison chaplain, waited on half-hour long holds and endured rude comments from staff. Officials the family spoke with at the prison and the hospital gave conflicting information on details ranging from Washington’s time of death to where officials found him, Tracie Washington said.

“I was never told anything,” she said. “So, how do you go on and bury your child, but you don’t even know what happened to your child?”

She said the prison owes her family an explanation.

According to Federal Bureau of Prisons policy, staff must alert next of kin identified in the inmate’s file or attempt to locate and notify them if no one is listed to coordinate where their remains and belongings will be sent. When they can, the warden must mail a letter of condolences that also outlines the cause of death. Later, the warden must send a copy of the death certificate to the family.

A spokeswoman for USP Leavenworth did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Benjamin O’Cone, a spokesman for the Bureau of Prisons, declined to comment on the cause of death or provide any information surrounding a possible death investigation, citing safety, security and privacy concerns.

Washington first arrived at Leavenworth on March 21 to serve a 30-month sentence.

He’d been convicted as a felon in possession of a firearm, the prison said in a news release. The U.S. Attorney for the District of Nebraska, where he was sentenced, said he was also convicted of conspiracy to distribute and possess methamphetamine. Officials recommended that Washington be allowed to participate in a residential drug treatment program and vocational and educational training while incarcerated. He was supposed to serve a three year term of supervised release after he got out of prison.

Washington had previously been convicted of multiple felony charges in Douglas County, Nebraska, including driving under the influence and drug and theft charges.

‘None of the stuff was adding up’

Eulice Washington, his aunt, said she first received a call from USP Leavenworth the morning of April 15, and was told that Washington had died.

But later that evening, the hospital called asking if family members planned to visit before his death.

The family made the nearly three-hour trek from Omaha and found Washington on life support in the hospital. He appeared to be breathing, but he wasn’t responsive. Someone at the hospital said Washington had needed six pints of blood since his arrival, but his condition hadn’t changed.

A nurse told the family they could decide when to pull the plug, but said it should happen by the end of the night, Eulice Washington said.

When they left the hospital, the family started piecing together some of the conflicting facts they’d heard from officials. At one point, someone told them Washington was found unresponsive in his cell, but another person said he was found in the shower. Other people who knew the family said they heard a rumor that several guards beat him.

Eulice Washington called the prison the Monday after her nephew died and asked to speak to the warden. The operator told her she never would and refused to give her their name, she said. The family was told the prison only has to provide them information regarding serious medical situations or death. Washington’s unresponsiveness and hospitalization, the family argued, was reason enough to warrant that information.

Later, she called the medical examiner, who said Washington had an enlarged heart, an underlying condition that often signifies other heart problems. As far as they knew, he was active, healthy and never had a history of heart problems.

After officials delivered Washington’s body to Omaha for the funeral, Tracie Washington said she found a golf ball-sized lump near his stomach that she believes had not been there before. She said no one at the hospital had mentioned it.

“None of the stuff was adding up,” Tracie Washington said. “None of it.”

An autopsy was performed, but officials told the family it could take 12 weeks to finalize the results.

When Washington first arrived at Leavenworth in March, Tracie Washington said he called her several days in a row. Her son loved to talk and called different family members as often as he could while incarcerated.

In their last conversation, she said Washington talked about the time he had to serve at Leavenworth and Tracie Washington told him to stick it out.

“It really wasn’t nothing bad,” she said. “He was like ‘I just have to deal with this place out here until I get out,’ but that was it.”

Then, the communication stopped. No one in the family had heard from him since around Easter, she said.

On Thursday, a few days before his death, the family said he was no longer listed in Corrlinks, a prison-monitored email for federal inmates. They don’t know what happened, Tracie Washington said, but knowing he was removed from the system a day before officials reported Washington unresponsive heightened the family’s worries.

“You’re not going to make me believe he just up and died,” she said.

‘They’re not making it a priority’

It’s common for prisons to stay tight-lipped about inmate deaths, said Wanda Bertram, a communications specialist for the Prison Policy Initiative. The nonpartisan nonprofit researches criminal justice reform and mass incarceration.

It’s also common, she said, for loved ones to learn from a cellmate or someone else that an inmate died or was hospitalized.

“Prisons, they’re just not making it a priority to tell people when their loved ones pass away,” Bertram said. “Actually, it can get even worse than that. There can be outright stonewalling by people who are trying to find out proactively what’s going on.”

Prisons often cite HIPAA to anyone seeking information on deceased inmates, Bertram said. But the law is vague about what information prisons are prohibited from sharing.

Family and other loved ones also often face barriers while trying to keep in touch with inmates and know about their well-being.

Because Washington’s family has received little communication from the prison and don’t know his cause of death weeks later, Bertram said they should be suspicious, even if the prison later tells them he died of natural causes. The general public, she said, should pay more attention to prison deaths and question the circumstances surrounding them.

“The prison has a lot of good reasons for not disclosing when someone has died in circumstances they would rather not talk about,” Bertram said. “The longer you go out from that person’s death, the harder it is to actually figure out the truth of what happened.”

‘We’re going to have answers’

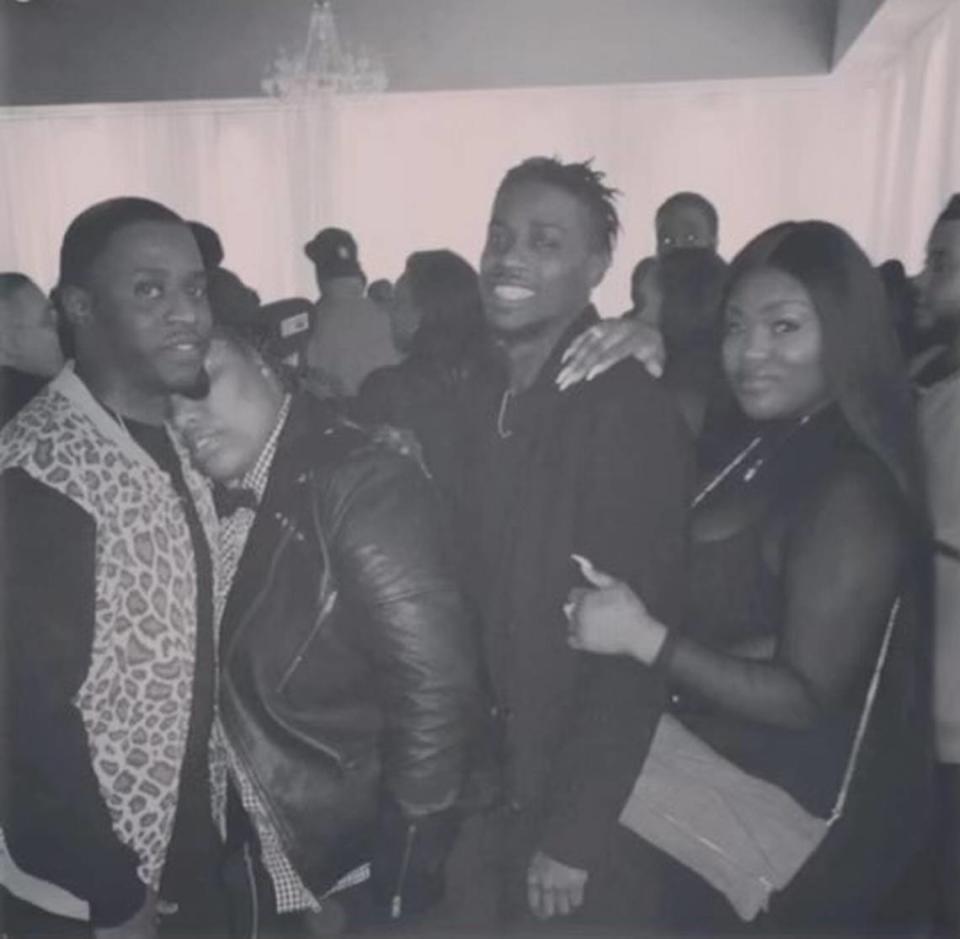

Washington’s family said he was witty and could hold his own in a debate with anyone. In high school, he was a two-time Nebraska state champion in wrestling and graduated with a 4.6 GPA, his family wrote in his obituary.

He studied sports psychology starting at the University of Northern Iowa and transferred a few times, but his aunt said he was only four credits shy of earning his bachelor’s degree this past fall from University of Nebraska Omaha.

Whether he was singing, dancing or cracking jokes, Demetrius Washington said his brother was always making others smile.

“The life of the party,” said Stephanie Soukup, Demetrius Washington’s fiancee. “Always good energy.”

Washington’s 14-year-old son has been taking the news hard, Tracie Washington said. His younger sons, ages six and seven, are having a difficult time processing what happened. He was a good father who still had the energy to wrestle and play with his kids, family said.

At the funeral, Tracie Washington said she brought one of the younger children to the casket, and he kept asking his dad to wake up.

While the medical examiner told the family about a possible heart problem, they’re skeptical. Since prison officials didn’t communicate much with the family and different officials told them conflicting information, they want to find other ways to get answers.

The family plans to hire an independent investigator to look into Washington’s death. They also intend to pursue any possible legal action against the prison or other officials who failed to communicate.

“They’ve been killing our people and getting away with it,” Eulice Washington said, “but they got the wrong family because we’re coming for their head. We’re not playing with them. We’re going to have answers and justice.”