Newport and the fleeting glitter of the Gilded Age | Opinion

Fred Zilian, a retired educator, gives tours of Newport and lectures on its history.

The storied Gilded Age of American history, with its epicenter in New York City and eventually in Newport, began 150 years ago. This age is at once part of the epic story of American capitalism’s astounding ability to create wealth, but also a cautionary tale of how great wealth can be squandered.

While most historians begin the age in 1870, the year 1873 is more apt. In that year Mark Twain and co-author Charles Warner published the novel “The Gilded Age," in which they offer vivid portrayals of greedy industrialists and corrupt politicians in Washington, D.C.

Also in that year, two eventual leaders of New York City high society met: Ward McAllister, the self-made social maestro of all things that glittered, and the commanding Caroline Astor, wife of William Blackhouse Astor Jr., the head of the Astor family, the richest in America in the mid-19th century. She became the undisputed “queen” of New York and then Newport society.

They both had been troubled by the many families who had only recently acquired wealth in the rapidly burgeoning American economy. These parvenus were attempting to wedge their way into high society; however, McAllister and “The Mrs. Astor” took it as their sacred duty to serve as the gatekeepers.

The preceding year, McAllister had prepared a list of 25 “Patriarchs” of high society New York. He said that these men “had the right [by blood and wealth] to create and lead society.”

Each of these Patriarchs was charged with inviting four women and five gentlemen to the first annual Patriarchs Ball in the winter of 1873. This list eventually approached the figure of 400, about the capacity of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom.

McAllister told the press: “Why, there are only about 400 people in fashionable New York society. It you go outside that number you strike people who are not at ease in a ballroom or make other people not at ease.”

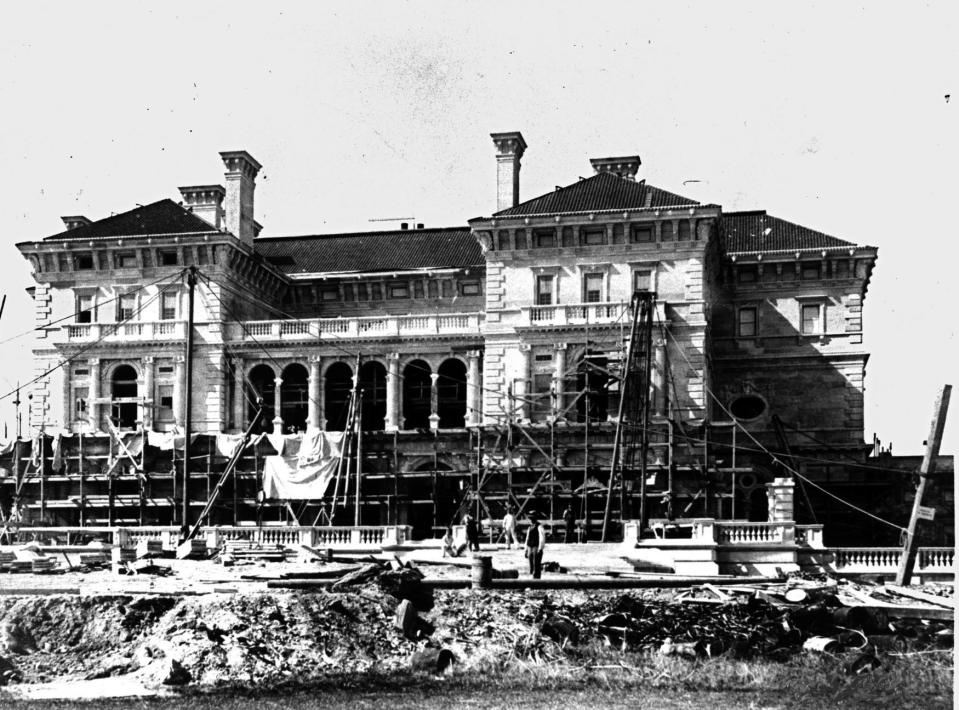

A decade later the center of New York society moved — for only the two prime summer months — to Newport. By the late 1880s, the Astors, Vanderbilts, Goelets, Belmonts, Fishes and others had bought property there seeking to escape the heat of city summers. They bought, built and staffed opulent mansions, which they called “cottages,” principally on Bellevue Avenue in Newport.

The great wealth that these families had amassed allowed them to luxuriate in a carefree summer idyll, what economist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption,” with social calendars packed not only with teas, dinners and balls, as in New York, not only with picnics in the beautiful venues the Newport area offered, but also with expensive hobbies.

At The Casino (1880), described as the most lavish resort in America, there was cards, croquet, tennis, dances and concerts.

With its wonderful harbor leading to Narragansett Bay, leading to the Atlantic Ocean, Newport was a marvelous location for sailing and yachting.

There was golfing at the Newport Country Club (1893), swimming at the exclusive Bailey’s Beach, the afternoon carriage rides up and down Bellevue Avenue, and — with the new century — events with the new “automotive machines.”

The four leaders of this high society included Caroline Astor, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, Marion “Mamie” Fish and Theresa “Tessie” Oelrichs. They and their husbands all owned mansions on Bellevue Avenue or nearby Ocean Drive.

Not the case with all these families, but certainly for the Vanderbilts, America’s richest family for several generations, the Gilded Age offers a cautionary tale. Vanderbilt scion Anderson Cooper writes in his book "Vanderbilt": “This is the story of the greatest American fortune ever squandered.” And Arthur T. Vanderbilt II writes in his book, “Fortune’s Children”: “When 120 of the Commodore’s [Vanderbilt] descendants gathered at Vanderbilt University in 1973 for the first family reunion, there was not a millionaire among them.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Newport and the fleeting glitter of the Gilded Age