50 years ago: When Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Notre Dame

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the South Bend Tribune on Oct. 18, 2013.

SOUTH BEND — Alabama's governor was calling for "segregation forever," police dogs and fire hoses were being turned on civil rights marchers in the South and four little girls died in the bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Ala.

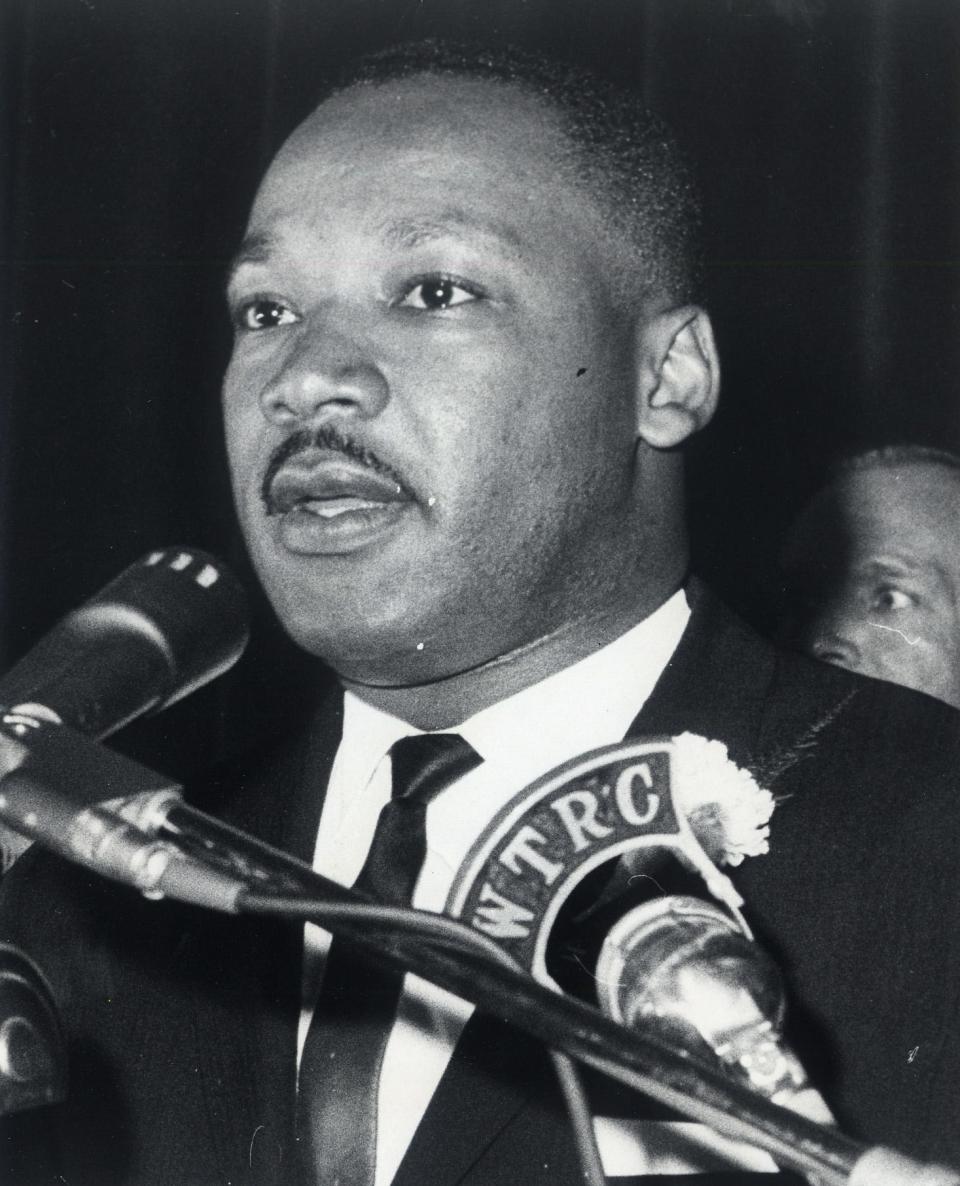

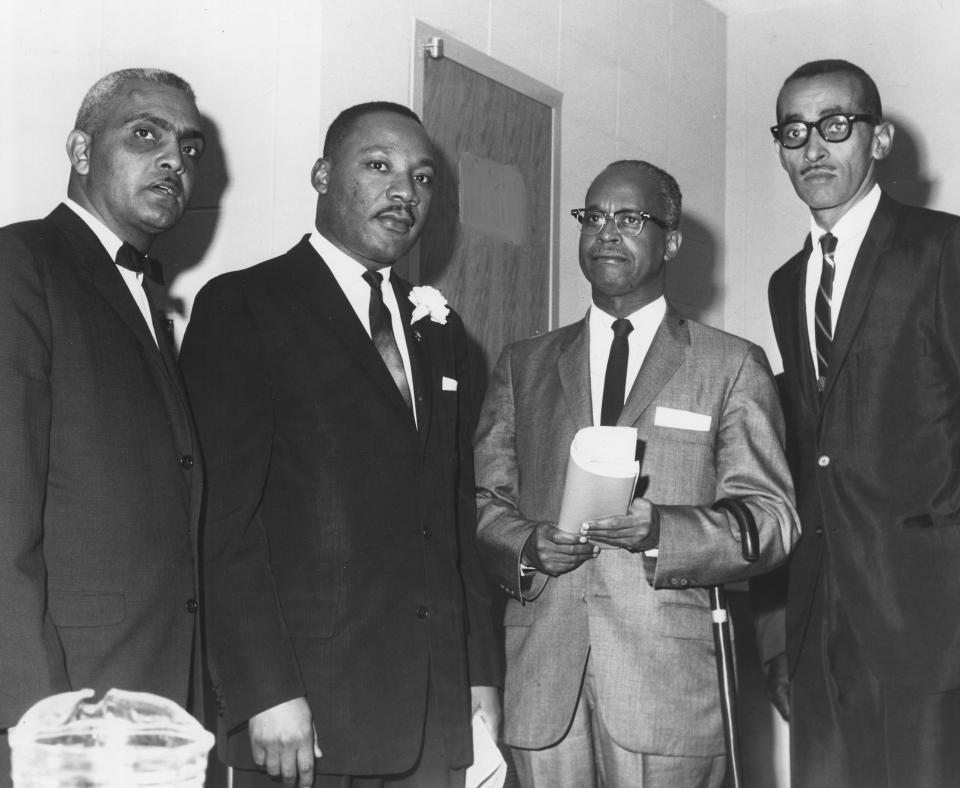

That was the backdrop 50 years ago today when the Rev. Martin Luther King visited South Bend and gave a speech to area residents at the University of Notre Dame.

"We must live together as brothers or die together as fools," King told the audience, according to the next day's South Bend Tribune. It was the civil rights leader's only public address in South Bend.

At the time, King was 34 years old and president of the Atlanta-based Southern Christian Leadership Conference. His visit here came less than two months after the March on Washington, at which he gave his now famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

It was a racially mixed audience estimated at 3,000 to 3,500 people who gathered in Stepan Center at Notre Dame to hear King speak.

"Science and technology have made today's world a neighborhood. We must make it a brotherhood," the national civil rights leader said.

King's visit was covered by reporter Kenneth C. Field, one of the first full-time African-American reporters on The Tribune news staff.

King told the audience that he'd rather have a strong civil rights bill presented to Congress and have it watered down later than have it watered down before it reached Congress.

"The law can't make you love me," he said, "but it can keep you from lynching me. Laws can't change the heart, but they can restrain the heartless.

"Morality cannot be legislated, but behavior can be regulated," he said.

The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965.

At a news conference earlier in the day, King said he didn't think Indiana could "boast of clean hands" in the area of race relations any more than other states.

"There was widespread public support for Martin Luther King's visit. There were at least 20 organizations that endorsed the event," says Monica Tetzlaff, an Indiana University South Bend history professor who researched the King appearance for a lecture she presented last month.

The organizers formed a broad coalition that included political leaders, unions, women's groups, and both Christian and Jewish organizations. A local organization known as the Citizens Civic Planning Committee led the effort.

King's message condemning discrimination in jobs, housing and education didn't apply only to the South, Tetzlaff says. At the time, minorities in South Bend were working to overturn housing discrimination. It took until 1968 to pass fair housing legislation in the city, she says.

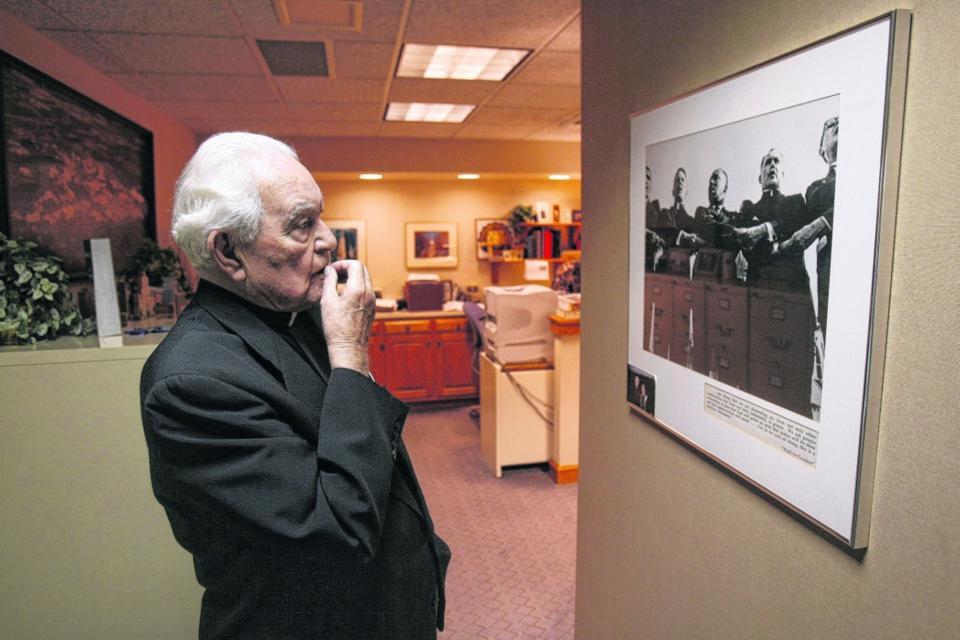

The Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, then president of Notre Dame and a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, arranged for King's speech to take place at Stepan Center.

A famous photo of Hesburgh and King linking hands in solidarity was taken in 1964, during a civil rights rally at Soldier Field in Chicago. The image was added to the Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery's permanent collection in 2007.

The civil rights leader arrived in South Bend by private plane. He was escorted into the city by a motorcade of about 50 cars, and about 20 police officers on motorcycles and in squad cars, according to Tribune coverage. He gave a brief news conference at a downtown hotel then attended a dinner in his honor at First Methodist Church, 333 N. Main St.

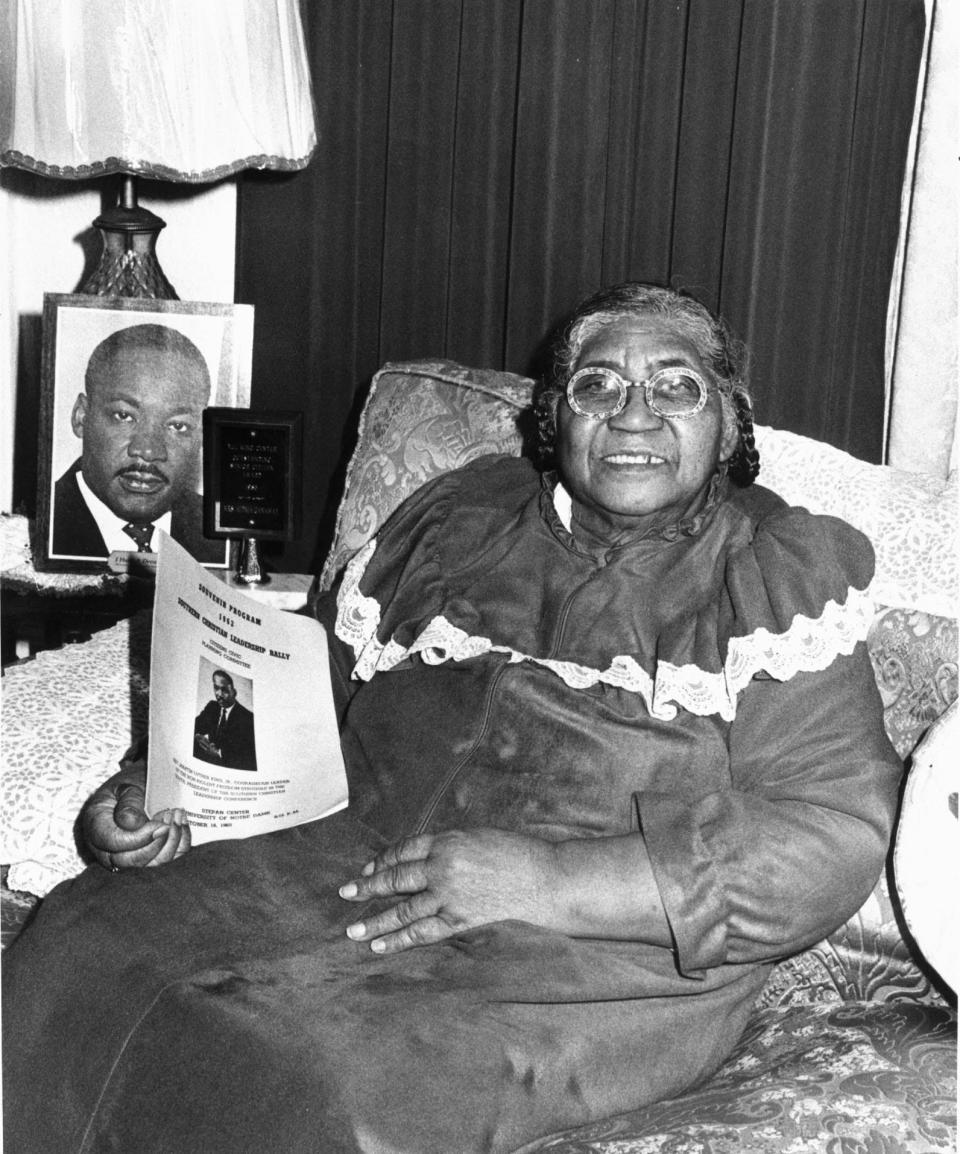

King "was a very good speaker. Everyone was proud to hear him speak," recalls Clara White, 96, of South Bend.

Her late husband — the Rev. Bernard White, pastor of St. John Baptist Church — helped arrange King's visit and served as master of ceremonies at the Stepan Center event.

South Bend resident John Charles Bryant was 25 and an active member of the NAACP when he helped with the planning to bring King to town.

"When he came here, the excitement was great," Bryant says. "He was a dynamic speaker. He was a person who put you in awe.

"Everybody was not a follower of Martin Luther King (in those days). There were mixed emotions about King, but the majority of people were for King's message of non-violence," Bryant says.

Bryant says he was grateful to be able to attend King's appearance here, because he hadn't been able to afford to travel to Washington, D.C., to participate in the historic March on Washington. "People needed someone to speak on their behalf and he understood," he says.

Tom Broden was a Notre Dame Law School professor who helped with planning. "There was widespread community participation," recalls Broden, now 89, of South Bend.

Some people locally might not have been pleased that King was visiting, but he was such a prominent leader by that point that any negative comments about his appearance here would have been viewed as childish, the retired professor says. No protests of the visit were noted in news coverage of the event.

Broden says he has strong memories of King's visit and has thought back on the experience often over the years.

"I was not only impressed with his message, but I was impressed with the way he delivered it," Broden says, describing King's visit as "one of the major events of my life."

What a year

The year 1963 was a pivotal year in the civil rights movement. Among the happenings:

■ Jan. 18: Incoming Alabama Gov. George Wallace calls for "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" in his inaugural address.

■ April 3 to May 10: The Birmingham, Ala., campaign challenges segregation with daily mass demonstrations.

■ April 12: The Rev. Martin Luther King is arrested in Birmingham for "parading without a permit."

■ April 16: King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail" is completed.

■ May 9-10: Images are televised of fire hoses and police dogs being turned on civil rights protesters.

■ June 11: Gov. Wallace stands in front of a schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama in an attempt to stop the enrollment of two black students.

■ June 11: President John F. Kennedy makes a historic civil rights speech, promising a bill to Congress the next week and asking for "the kind of equality of treatment which we would want for ourselves."

■ June 12: NAACP worker Medgar Evers is murdered in Jackson, Miss.

■ June 19: Kennedy sends Congress his proposed Civil Rights Act.

■ Aug. 28: March on Washington, D.C., occurs and King gives his "I Have a Dream Speech."

■ Sept. 15: 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham kills four girls.

■ Nov. 22: President Kennedy is assassinated.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Notre Dame in 1963