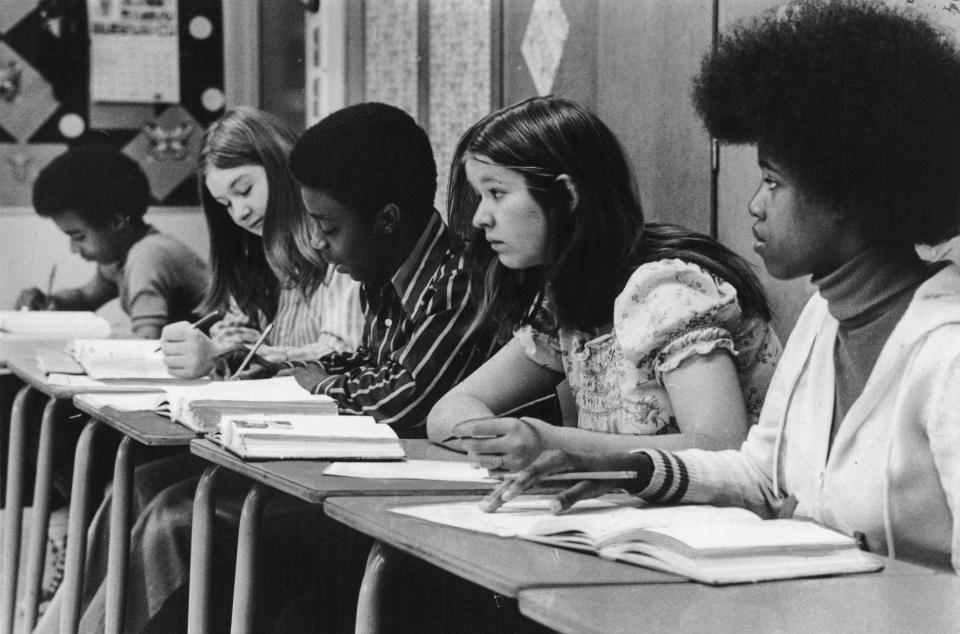

50 years after SCOTUS made a decision in Detroit desegregation cases, schools remain divided

While some suburban school districts in metro Detroit have become more diverse in the years since a U.S. Supreme Court decision effectively barred districts from desegregating over district boundary lines, Detroit and a handful of suburban districts have become more divided by race since 1975, a Detroit Free Press analysis has found.

Specifically, suburban school districts lining Detroit — including Southfield, Oak Park, and Harper Woods — have been shaped by decades of white flight as the number of Black families in those areas increased.

"Black folks moved to those inner ring suburbs, like Southfield, for example, then white folks who had moved to those inner ring suburbs, they moved farther out," said Joyce Baugh, a professor emeritus at Central Michigan University. "What you have then is people who talk about wanting to send their kids to neighborhood schools. If the neighborhoods are segregated, then what's going to happen?"

Researchers say these splits are in part a legacy of Milliken v. Bradley, a federal court case ultimately decided by the Supreme Court in a decision that came down 50 years ago Thursday, on July 25, 1974. The Milliken case started in 1970, after the NAACP sued then-Michigan Gov. William Milliken over what the organization claimed was intentional segregation in Detroit's schools. While a lower court judge ordered Michigan education officials to draw up a desegregation plan involving Detroit and surrounding suburban school districts, the Supreme Court overturned that order, ruling 5-4 that "a federal court may not impose a multidistrict, area-wide remedy" to desegregate schools.

"In the aftermath of Milliken, public education remained highly segregated in metro Detroit," said Thomas Sugrue, a historian and professor at New York University. "And we witnessed even more fragmentation of the metropolitan area as a result."

The consequences of Milliken are wide-reaching. But what is often misunderstood about the case and school desegregation broadly, Baugh said, is that desegregation efforts were about resource equity — districts like Detroit were often starved for resources and students did not receive an equitable education compared with their white peers because of it. Inequitable school funding is an issue that researchers and advocacy groups say persists today.

"The theory behind desegregation, back in the time of Milliken and since, it wasn't that Black kids needed to sit next to white kids and they would learn better," Baugh said. "The idea is that the resources would flow."

Before the SCOTUS ruling, the Michigan Department of Education had begun work on trying to understand segregation in Michigan schools as it brainstormed a multidistrict desegregation plan, conducting multiple district-by-district census studies. The Free Press analyzed a state school census report dated 1975 and compared it with demographic data from the 2023-24 school year for southeast Michigan.

The numbers show:

Many of the districts in suburbs lining Detroit have since flipped from a majority white student body to a majority Black student body. In 1975, the Southfield Public School District was 96% white, with just 2% Black students. This school year, 92% of Southfield students are Black, 2% are white, signaling pervasive white flight. Harper Woods did not have a single Black student to report in 1975, while today 87% of the district's students are Black.

Detroit Public Schools Community District has shrunk considerably from the city's heyday, from 257,006 students to 48,476 students. And while roughly a quarter of students, 26%, were white in 1975, just 2% of Detroit students are white this year, signifying considerable flight from the city.

Many southeast Michigan school districts do have more students of color: 57% of schools in 2023-24 have 70% or more white students, compared with 96% of schools in 1975.

An attempt to desegregate Detroit schools thwarted

In the 1960s, Detroit schools operated on attendance boundaries, so students in particular areas of the city would attend the school that corresponded to where they lived. But racist housing policies often meant Black Detroiters were relegated to certain areas of the city, rendering schools segregated by race. Only about 2% of students at Cody High School at the time were Black while nearly 95% at Mumford High School were Black, according to Baugh's book, "The Detroit School Busing Case."

In 1970, Detroit's school board passed a voluntary desegregation plan of the city's high schools, which was met with opposition from white families, sparking a walkout of white students, according to the State Bar of Michigan. In response, Michigan's state Legislature repealed that plan.

The Legislature's decision to repeal the plan prompted the NAACP to sue Michigan's governor, Milliken, in August 1970. Attorneys argued that housing policies such as redlining, in which neighborhoods made up of mostly people of color were deemed unworthy of housing investments, and other practices that directed Black residents to segregated areas of the city.

"One of the things that the attorneys for the Bradley plaintiffs would talk about was the containment pattern," Baugh said. "You would make sure that the African Americans were always contained in the central city. So those schools, unless you do something with the school, something affirmative to disrupt that pattern, you're going to have segregated education."

A district court judge in Michigan, Stephen Roth, ruled that metro Detroit schools were segregated, and ordered the Michigan State Board of Education and Detroit schools to draw up a desegregation plan, according to the University of Michigan library. Largely white groups and school districts began to oppose the plans presented in court, which would have included suburban schools in busing proposals.

But by 1974, the case had made its way to the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in a 5-4 vote that the district and the state could not be ordered to implement a desegregation plan involving outside districts, limiting how much power states and districts had in crafting approaches to desegregation. Those limits persist today, experts say.

What happened after Milliken

In the 1980s, Dara Hill attended Burton International, which was then a magnet school and a part of what became a strategy following Milliken to continue integration efforts through a voluntary basis, trying to attract parents with the promise of a more academically rigorous or unique programs. Burton, for instance, offered bilingual education so students would learn multiple languages.

Hill, now a professor in the college of education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, researches school choice and supports for students of color. She enjoyed attending Burton, and said she recognizes now its existence was, in part, a response to Milliken.

"It was like a Band-Aid, a remedy to the harm that was caused by Milliken v. Bradley," she said. "And so although I lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood, I attended racially integrated citywide schools, which was really an amazing experience."

She still lives in Detroit, though she witnessed many classmates move away. But in 2010, around the time her daughter Norah was born, she witnessed more middle class families moving into the city with young children, recognizing the benefits of historic homes that cost considerably less than housing prices in the suburbs. Hill created the Best Classroom Project, where members of the group visited and reported back on public, private and charter schools across the city.

"I think there's been a sensitivity about wanting to keep things as equitable as possible without offending people, and being a part of the advocacy with everyone, as opposed to, 'We're going to come in and take over and push you out,' " she said.

At the time, she was looking to enroll Norah in school, and ended up choosing University Liggett School, a private school in Grosse Pointe Woods. Hill was thinking both as an education researcher and a parent, trying to find a program that would be rigorous for Norah, who was reading at an advanced level. Overall, parents learned the complexities of choice in Detroit through the project, she said.

But largely, Detroit has remained "so intensely segregated," said Jeremy Singer, an assistant research professor in education at Wayne State University. Some of the reason for that has to do with geographic limits: People like to choose schools nearby, because transportation can be difficult for parents and Detroit Public Schools Community District offers limited transportation support, due to limited state funding for transportation.

And while families do have choices — they can enroll their students in charter schools or in school districts with open enrollment policies — geographic boundaries keep those options finite.

"Those students who leave the city are heavily concentrated in just a handful of schools in just a handful of districts that are more or less border districts," he said, adding: "If school choice was imagined to be a solution in the wake of the Milliken versus Bradley ruling it never ... has been a solution for integration."

How district enrollment patterns have changed

School enrollment data between 1975 and 2024 does not offer a perfect comparison. For instance, the definitions of race/ethnicity have changed, according to Jim Hines, spokesperson for Michigan's Center for Educational Performance and Information, the state agency that collects public education data, particularly when it comes to categorizing Hispanic students.

But the numbers can at least illustrate some of the wide-ranging changes metro Detroit schools have experienced.

For instance, numerous districts on the very edge of the metropolitan area — including Dexter, Chelsea, Brighton, Howell and Lake Orion — have experienced very little shift in the number of Black students attending those districts since 1975. Dexter Community Schools, for example, went from 0% Black students in 1975 to 1% in the 2023-24 school year.

School districts closer to Detroit, however, became more diverse. Roseville, Farmington Hills, Ferndale and more all serve considerably more Black students than in 1975. The reasons for many of these changes are complex, said Singer, and have to do with larger regional trends over the last 50 years.

"It is the case that some suburbs have become both residentially and educationally more diverse as a result of families moving to the suburbs, from city centers over time," he said.

In other cases, open enrollment, which allows students from outside district boundaries to attend schools within a district, has allowed districts to increase enrollment numbers. Districts like Oak Park and Harper Woods have attracted a large student body from Detroit through open enrollment, he said.

Today, education advocates say racial segregation following Milliken has driven long-standing inequality among schools, with districts in higher income areas benefiting from more resources to provide a stronger education. They've turned to advocating for funding equity to combat these inequalities, wrote Amber Arellano, executive director of The Education Trust-Midwest, an education advocacy organization.

"Racial segregation between Michigan school districts remains a persistent and troubling problem — the very issue Milliken attempted to solve in Detroit half a century ago," she wrote. "These racial divides often align closely with socioeconomic divides, with a disproportionate share of Michigan students of color attending school in districts with the highest concentrations of poverty."

State lawmakers have made some advances in attempting to fund schools more fairly, allocating targeted funds every year to school districts that serve higher proportions of students in poverty.

Still, it didn't have to be this way, Baugh said. The vehement argument against busing could have given way to working out a system where some students living on the border of the city could have walked to the suburban schools on those borders. Policymakers could have found a way to ramp up resources to long-suffering districts like Detroit sooner.

"It's one of those things that I just feel like it didn't have to be this way," she said. "Writing this book, it was a lot of work, but it was also a lot of emotion, because there were some days, literally, I would just cry because it was just bad, and that's the thing, people don't want to acknowledge it. That's what I think is a big part of our problem in this country, is we won't acknowledge what happened."

Contact Lily Altavena: laltavena@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: 50 years after historic Detroit desegregation case, here's what's changed