A Notorious Type of Legislation Is Back With a Vengeance

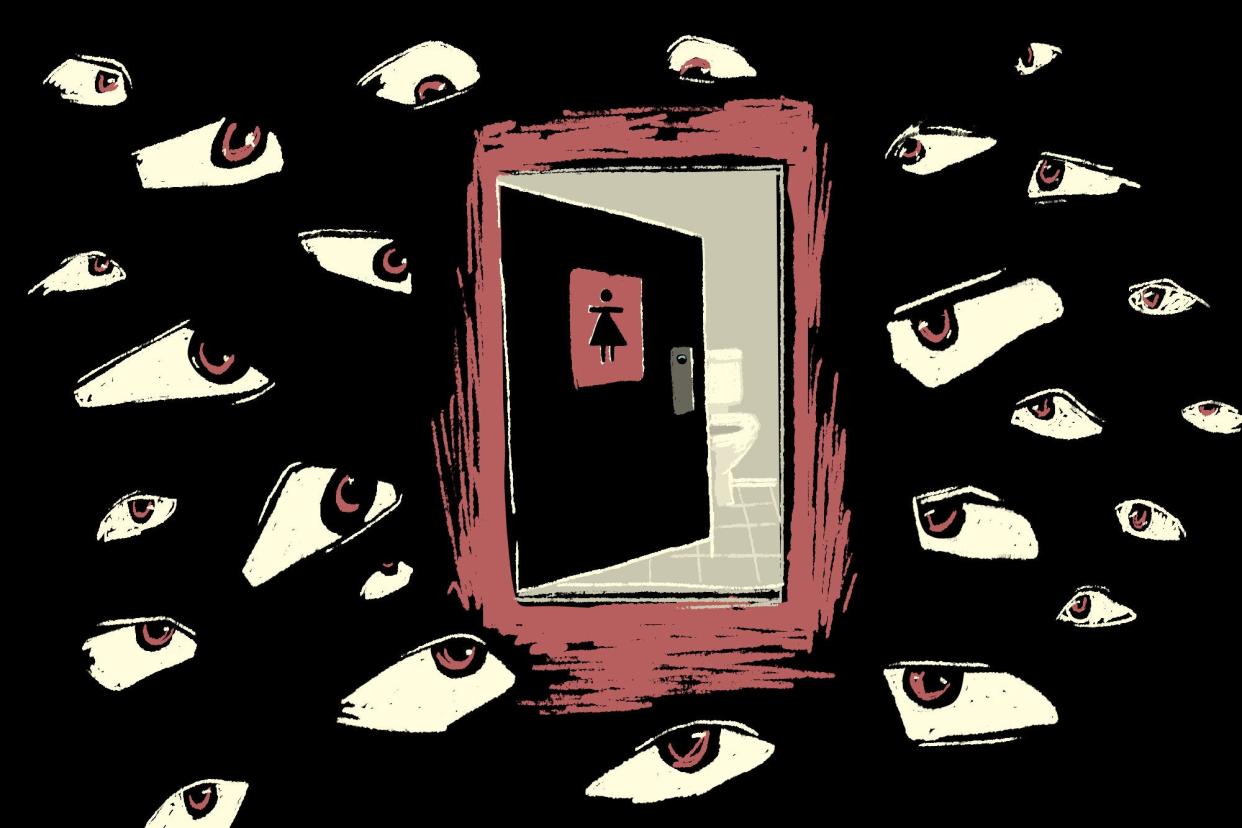

As North Carolina lawmakers were debating House Bill 2 in March 2016, Ames Simmons pulled over his car so he could listen to the votes roll in. At that point, the now notorious legislation was a novelty; the statute would force trans people to use restrooms and changing areas based on their sex assigned at birth in restaurants, cafés, gyms, and other public spaces. Republicans had introduced HB2 in response to a municipal ordinance in the relatively progressive city of Charlotte that granted trans people equal access in all areas of public accommodation—which critics alleged, without evidence, would result in predators “in dresses” exploiting the rule to prey on women and children.

It took the Republicans just 11 hours and 10 minutes to introduce, pass, and enact HB2—a speedy route to making North Carolina the first state in U.S. history to regulate public bathroom use based on trans identity. As he absorbed the news from his radio, Simmons remembers “feeling the beginning of this dread that transgender people’s rights to be who we are was starting to deteriorate.” He would take a job later that year with Equality North Carolina as its transgender policy director, and one of his top priorities would be the campaign to repeal HB2.

“I had just completed the social and legal aspects of gender affirmation a couple of months earlier,” Simmons recalled of the moment. “I convinced myself that it was finally OK to transition. HB2 made me worry that my confidence might have been misplaced—although I, like many trans people, really didn’t have any real choice.”

For a time, it seemed like the deterioration Simmons feared might be preventable and that North Carolina would be an outlier in telling trans people where they were permitted to pee. As you may recall, the Tar Heel State faced widespread threats of boycotts from corporations, artists, and other organizations, ranging from Deutsche Bank nixing a planned expansion to the NCAA threatening to no longer host title games in the state. Even Bruce Springsteen—the Boss himself—canceled a scheduled concert. The potential financial fallout, estimated to cost North Carolina $3.7 billion over 12 years, led to a compromise resulting in the law’s eventual repeal. A year after HB2’s passage, it was replaced with a law temporarily banning local municipalities like Charlotte from setting their own public accommodations laws until December 2020.

Other attempts to pass anti-trans restroom bills in this era were even less successful, hampered as they were by similar economic pressure. An oft-overlooked fact is that South Dakota actually beat North Carolina in sending a bathroom ban to its governor’s desk. Then-Gov. Dennis Daugaard, a Republican, vetoed HB 1008 in February 2016 over concerns it would imperil the state’s $3.8 billion annual tourism revenue. The failure of Texas’ own attempt at regulating trans restroom use the following year was largely attributed to a fiscal note attached to S.B. 6 warning that its passage could cost the state $3.3 billion each year it remained on the books. Despite calling three special sessions of the Legislature in part to ensure S.B. 6’s triumph, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott would declare by September 2018 that a bathroom ban was no longer on his priority list.

As a result of this series of belly flops, Republicans were, for a few years at least, loath to touch bills restricting trans restroom access, even as they pursued an unprecedented state-level legislative assault on the trans community in general. In 2021 and 2022, just 11 anti-trans bathroom bills—in total—were filed to state legislatures, according to data compiled by Trans Legislation Tracker. Not a single one passed.

But lest you think the bathroom bill is a thing of the past, it has recently witnessed a quiet reversal of fortune—with almost none of the public outcry that greeted HB2. In March 2023, Arkansas became the first state since North Carolina to enact a law limiting public facility access for trans people. Over the past 15 months, at least 12 states—to date—have enacted laws that bar individuals from using restrooms and locker rooms that don’t align with their “biological sex” in either K-12 schools, prisons, or other buildings operated by the state government, such as museums, airports, and state parks. Florida’s especially draconian bathroom ban, passed in May 2023, is the first to attach criminal penalties to its violation: Breaking the law is a misdemeanor trespassing offense, punishable by up to a year in jail.

Even more anti-trans restroom laws could be enacted within the coming weeks. A bathroom bill is soon headed to the desk of Republican Gov. Mike DeWine, who once vocally opposed legislation targeting the trans community before making an abrupt about-turn earlier this year. This, unfortunately, is the state of trans rights in 2024: Nothing can be taken for granted, including threats long thought to be defeated.

While many of us may have assumed that the GOP would move on from bathroom bills for good following HB2’s defeat, advocates say that notion was always misguided.

Gillian Branstetter, a communications strategist for the American Civil Liberties Union, says that Republicans initially chose to focus on restroom use because they figured it was the “path of least resistance,” before recalibrating their strategy. That doesn’t mean, however, that the desire to restrain the ability of trans people to move freely in public simply went away.

“Queer folks can be prone to a kind of wiggly view of history where we’re just always progressively marching forward,” Branstetter says. “There’s this really narrow and shallow story we told about queer rights, which is that we came out of the closet, went into the streets, and fought for increasing visibility. That slow, liberal process is how we secured a right like marriage equality. Marriage equality was always a very small-c conservative goal, and fighting for the rights of queer folks to be openly queer in public spaces was always going to be more threatening to the far right. It was always going to be a harder fight overall.”

The new wave of bathroom bans created chaos in their respective states because—among their many obvious, glaring problems—the bills do not specify how they should be enforced. That has led to widespread confusion in Florida, where members of the public are reportedly enforcing the law through vigilante means. A Daily Beast story published in May reported several cases in which cisgender people have taken it upon themselves to police restrooms in areas like movie theaters and shopping malls—where, in fact, the state’s law does not actually apply. Meanwhile, the office of Utah state auditor John Dougall has reportedly received more than 12,000 reports of trans people contravening the state’s newly enacted bathroom ban—which applies to governmental facilities but not private businesses—but has been unable to substantiate a single claim. Some of those reports were filed by LGBTQ+ people and their allies trolling Utah, while others were presumably genuine concerns; either way, it’s clear the reporting system itself is fundamentally unworkable.

Sue Robbins, a longtime trans activist in Utah, fears her state’s bill will be used to target cisgender people as well as trans people. Consider that just this year, there have been two separate incidents of student athletes in Utah being falsely accused of being transgender with the intent of disqualifying them from competition under the state’s trans sports ban. (One accuser was the father of a player on an opposing basketball team, and the other was a local school board member.) Because there’s no way to easily tell what someone’s gender identity is from the outside, Robbins says that cisgender people who want to enforce anti-trans laws often rely on crude stereotypes.

“We get into some of those social issues where there may be people judging the bodies of people and trying to tell them whether they belong somewhere,” she says. “By trying to target the transgender community, they target a lot of people outside the trans community, because people really don’t understand what being transgender is. They just look for masculine features” to decide who is transgender.

It’s hard not to notice that this time around, these laws have been met with virtually none of the fallout that attended HB2’s passage.

What’s different now? Oakley believes that for one thing, the muted response to the new generation of trans restroom restrictions is due to the sheer proliferation of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in recent years. When HB2 was enacted, it had to compete with just 55 other anti-trans bills for the attention of executive leaders and the public at large. But if corporations wanted to apply HB2–like pressure in 2024, they now would find themselves in conflict with almost half the country: Currently, 25 states have laws or policies on the books limiting trans people’s sports participation, and the same number have partial or full bans on trans youth medical care in place. In that ongoing campaign to restrict the rights of trans Americans, Oakley says Republican legislators realized there was “strength in numbers.”

“Bathrooms went from being ‘This is something that if you try to do it, you’ll experience intense condemnation’ to ‘If you all do it together, then no one state can be ostracized,’ ” she says. “There were so many states that just started hitting these horrible bills at the same time that they didn’t experience that same kind of blowback that some of the states had experienced earlier on.”

Of the bathroom bans currently in place, exactly half of them—or 6 of 12—specifically focus on regulating facility use in public schools. When Arkansas passed HB1156 in March 2023, creating a wave of copycat laws in other states, the legislation was a watered-down version of a far more extreme proposal that would have charged trans people with “misdemeanor sexual indecency” for using the public restroom that aligns with their identity in the presence of a minor. (That charge is punishable by a year in prison and a $2,500 fine.) The revised version of HB1156 instead subjected schools to a $1,000 fine if they don’t force trans students to use gender-incongruent facilities.

When Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed the bill into law, a spokesperson said in comments to the press that “our schools are no place for the radical left’s woke agenda” and claimed that affirming the identities of trans youth amounts to “indoctrination.” “Arkansas isn’t going to rewrite the rules of biology just to please a handful of far-left advocates,” a representative for Sanders said.

The shift in focus speaks to the larger rebranding of bathroom bills, which have piggybacked on the successful ongoing assault on the rights of trans youth and the weaponization of “parental rights.” While the idea of predatory boogeymen lurking in the shadows never quite caught on with the American public (even Donald Trump, of all people, admitted he didn’t buy it), the Bathroom Bill 2.0 has capitalized on a fallacious yet widespread panic about “grooming.” According to anti-LGBTQ+ conservatives, even basic support for trans youth, whether that’s allowing them to use the bathroom that’s most comfortable for them or respecting their pronouns, is tantamount to child abuse. By passing laws denying them those very privileges, Republican lawmakers across the country have claimed that they are actually protecting young people—that is, from the pernicious influence of liberalism.

Focusing on schools fits the larger Republican playbook of previous moral panics, according to Erin Reed, an independent journalist and researcher. She says that moral panics of the past—from fears in the mid-20th century that marijuana use would result in societal upheaval to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s—have largely focused on using children to advance a far-right agenda. Bathrooms are an ideal means of exercising those aims, she notes, because access to them has so often functioned as a tool of subjugating marginalized people. For example, denying women the ability to use public restrooms was a means of keeping them confined to the home until the late 19th century, when Massachusetts became the first state that required businesses to provide women with their own bathroom.

“The restrictions on bathrooms have been used for a very long time to target disenfranchised people,” Reed says. “The ability to use the bathroom in public is what makes it possible to travel. It’s what makes it possible to leave your home. It’s what makes it possible to attend events. If you start to restrict the ability to use the bathroom, it’s a very easy way to make a population disappear or push them into a place where they cannot be seen or where they can’t leave their homes.”

Republicans are likely to keep pushing anti-trans bathroom laws in the next few years after largely maxing out on bills restricting trans youth access to gender-affirming medical care or sports participation (whereas 19 states passed gender-affirming care bans last year, just three have so far in 2024). The fact is, the states that are going to restrict those rights and protections have already done so.

With few other places for the anti-trans movement to go, LGBTQ+ rights groups fear that the probable expansion of bathroom bills will only increase hostility toward trans people as they go about their daily lives. Louisiana Trans Advocates immediately began receiving panicked phone calls in early June after the state’s Republican governor, Jeff Landry, signed HB 608, a bill restricting trans restroom use on government property. Members of the local trans community, unaware of the specifics of HB 608, were unsure of what they would need to do to follow the law: Could they still go to the bathroom at work? What about rest stops and gas station bathrooms?

Louisiana Trans Advocates posted a Know Your Rights explainer on its site to help trans people better understand what HB 608 does and does not do. But Peyton Rose Michelle, the organization’s executive director, knows the sad fact is that the vast majority of the public won’t read it. She is worried less about how the law will impact the ability of trans Louisianans to safely use the bathroom—noting that most people are in and out of the restroom in a few minutes, usually with little interaction—and more how it might impact individuals while they try to go about their daily lives. Several trans Louisianans have lost their lives to violence since 2020, including Brooklyn Smith, Keeva Scatter, Queasha Hardy, and Shaki Peters, all of whom were Black women. Louisiana’s bathroom law will make a marginalized group even more vulnerable, Michelle says.

“These bills are about creating just a worse environment in general and sending a message that disrespecting trans and queer people is—in their opinion—the right thing to do,” she says. “We’re wandering down a slope where things will be getting worse.”