The Biden-Trump presidential debate was a disaster, but not just for obvious reasons

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

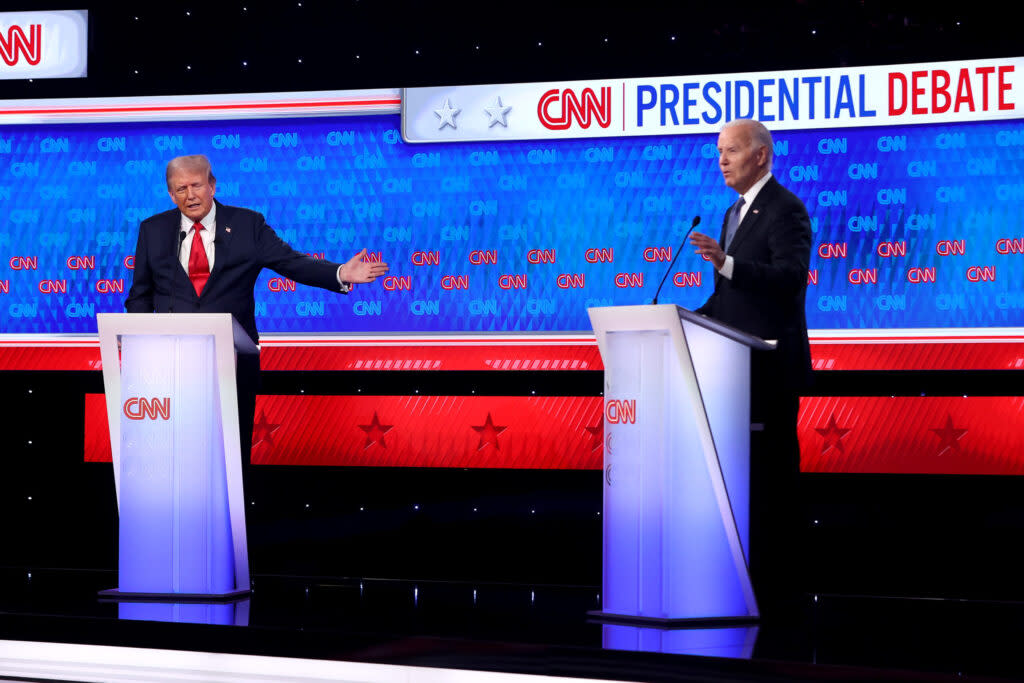

President Joe Biden, right, and the Republican presidential candidate, former U.S. President Donald Trump, participate in the CNN Presidential Debate on June 27, 2024, in Atlanta, Georgia. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

In the days following the Biden-Trump debate, news stories and Facebook posts introduced a new term for many — Gish Gallop — defined roughly as throwing out numerous arguments that are typically unsupported by facts making it difficult to respond.

The debate strategy was named in 1994 for Duane Gish, a creationist advocate who was known for spewing a voluminous number of arguments and frustrating opponents. For those of us with an academic debate background, “the spread” tactic predates Gish by several decades and has frustrated many debaters who have four or five minutes to respond to 12 or 15 minutes of negative attacks and bolster their own arguments.

CNN’s debate format limited rebuttal time to one-third that of the candidate with the initial response. Many are explaining away President Joe Biden’s underwhelming performance to the Gish Gallop. The format and the moderators’ decision to include open-ended questions and few follow-ups to discern detail or factual basis were conducive to the technique. It made it easier for former president Donald Trump to evade, advance arguments on multiple topics — many not germane to the question — and get away with unsupported claims.

Fact check sites show that Biden also made claims that he did not support, although there were far fewer of them. Some of his responses also included several topics unrelated to the question.

Biden was at a tactical disadvantage, but he also did not have a clear strategy focusing on strengths and isolating his arguments and attacks on Trump on the most critical issues. Many of Trump’s arguments are easily subsumed under such key issues, and a lesson from academic debaters is to group them in a way that bolsters Biden’s accomplishments without getting into the weeds.

On the economy, for instance, Biden only needed to quickly summarize a bipartisan Joint Economic Committee Report on Trump’s economic record (lost jobs, slowest growth, higher unemployment at his term’s end than beginning, record unemployment, smaller number in labor force) and dismiss much of his “galloping.”

Similar to what happened to President Ronald Reagan in his first 1984 debate with Walter Mondale, Biden was likely overburdened with too many facts in his debate preparation and may have been coached to respond to everything Trump said. Reagan’s polling dropped by 7 points afterward, but he redeemed himself in the second debate, quipping about not letting Mondale’s youth and inexperience become an issue.

The differences between the two men and the two debate scenarios are that Biden is eight years older than Reagan was when he ran for a second term — and arguably more frail — and the timing is different. The second debate where Reagan redeemed himself was held two weeks later rather than 10. Both debates were after the nominating conventions, thereby eliminating any panic that the candidate needed to be replaced.

By having the earliest debate in general election history, candidates did not lay out their vision in an acceptance speech and practice it for weeks before the debate. That might have helped Biden focus his arguments.

I’ve studied and researched political debates since I was an undergraduate. I served on an advisory board for the Commission on Presidential Debates from 1987 to 2000 and helped develop debates in several new democracies. In 1996, I used a grant from the Ford Foundation to expand my focus group research through creation of DebateWatch for the commission. I’ve published numerous articles on formats and co-edited two books with the focus group results. I continue to conduct DebateWatch groups and will again for the Sept. 10 debate.

What I’ve learned is that the June 27 debate did not serve the needs of voters, especially undecideds, for several reasons. It wasn’t just because Biden had a “disastrous” night and Trump lied.

From an educational and substantive perspective, the questions and the structure did not illuminate the key issues, differences and what is at stake in the election. Both created a chaotic debate with multiple topics offered in every response, and not just from Trump. Question structure impacts responses, and it mattered. CNN chose to return to a format with multiple moderators, a large number of questions, and few probing follow-up questions. The last was done to keep the moderators out of the debate or not ask “gotcha” questions.

Thousands of pages of focus group transcripts between 1992 and 2004 indicate that viewers want tough follow-up questions and clarity on “factual statements,” especially when the format limits rebuttal.

Asking Trump to respond to a letter by 16 Nobel economists claiming that “We believe that a second Trump term would have a negative impact on the U.S.’s economic standing in the world and a destabilizing effect on the U.S.’s domestic economy” is not a ”gotcha” question and should have been asked. The letter was released two days before the debate. Such a question lays out an important issue and then leaves it up to Biden to contrast his policies.

Asking follow-up questions to support a candidate’s claims is not becoming a debater. Would it be better to come from the opponent? Yes. But there was no cross-examination, and as indicated, one-third the time to respond. Candidates seldom respond to one another’s questions.

Focus groups repeatedly asked for fewer questions and more time on each.

Over the past several debate cycles, the commission delivered on that request, with six 15-minute segments that enabled more depth and provided more rebuttal opportunities. It also announced the topics in advance. By doing so, the candidates knew what was going to be asked, and they had less reason to throw in everything on their agenda with each question to make sure it gets into the debate.

CNN’s debate started with the economy and near the end had additional economic oriented questions such as Social Security. There was no logical flow of topics from one point to another at times. By having blocks of time devoted to key issues, moderators can push candidates toward specifics and better remind the viewing audience of what the topic is and why it isn’t being addressed through targeted follow-up questions. Some of this was done late in the debate, primarily by Dana Bash, but it was too little too late.

Voters also want to hear about specific plans for the future, not just a rehash of what a candidate did as president. The latter is important because it demonstrates a direction an incumbent will take based on past performance, and in this historic debate, there were two real world examples. However, looking to the future is equally important, and both purposes can be served.

The first question in the debate is an example: “President Biden, inflation has slowed, but prices remain high. Since you took office, the price of essentials has increased. For example, a basket of groceries that cost $100 then, now costs more than $120; and typical home prices have jumped more than 30 percent. What do you say to voters who feel they are worse off under your presidency than they were under President Trump?”

Biden responded by talking about Trump’s record and what a sorry economy he inherited, his family in Scranton and recognizing that people still face economic challenges. He did give some solutions on housing — capping rent and building 2 million new units — but nothing on how it will be done, and there was no follow up asking why it wasn’t done in this term. He talked about corporate greed but didn’t say what he was going to do about it.

If the question were changed to: “What would you do in a second Biden term to reduce inflation and the cost of housing?” it puts the focus on the future and doesn’t allow the candidate to take it any direction they want. By framing the question on the future, it allows for a follow up requesting specifics. It would force Biden to provide a reason to expect something different or explain why he hadn’t done more to date.

Again, this is not a “gotcha” question or intruding into the debate. It is holding the candidates accountable for their claims.

Such a question would also allow for a follow up to Trump to describe how to solve the problem. Jake Tapper did ask about Trump’s proposed tariffs in a follow up, but not about the primary issue of resolving kitchen table problems. Tapper also allowed Trump to get away with a general claim when he asked: “You want to impose a 10% tariff on all goods coming into the U.S. How will you ensure that that doesn’t drive prices even higher?”

Trump said: “Not going to drive them higher. It’s just going to cause countries that have been ripping us off for years, like China and many others, in all fairness to China — it’s going to just force them to pay us a lot of money, reduce our deficit tremendously, and give us a lot of power for other things.”

There was no follow-up noting the economists’ letter or even CNN’s website, which states: “Economists generally agree that tariffs drive up prices. JP Morgan economists estimated in 2019 that Trump’s tariffs on about $300 billion of Chinese-made goods would cost the average American household $1,000 a year.”

The format only allowed a single optional rebuttal response so Trump’s claim went unchallenged in light of history and current warnings. Tapper shifted to a new question about the deficit, leaving most struggling Americans unsure how either of them would address pocketbook issues.

There are numerous other examples throughout the debate of missed opportunities to enlighten the public on issues where both men have weaknesses and where truth is not always obvious.

One other important omission from this year’s two-debate schedule and formats is that there is no public voice. The town hall was introduced in 1992 and widely popular with focus groups. It is more difficult for a candidate to ignore a question from an undecided voter a few feet away. Members of the public ask questions in the way they think about them, not the way journalists or politicians do. Some primary debates have included questions submitted by viewers, and not even that was done.

Our debates have never been perfect. The winner of a debate does not always win the election — Walter Mondale, John Kerry, Mitt Romney and Hillary Clinton all attest to that fact. However, for undecided and wavering voters, they do serve a useful purpose. The average voter is not a policy wonk or a news junkie, and many who are only hear one side. A debate should be structured in a way that candidates are held accountable for past performance and make a case for the future.

The debate last Thursday did neither well.

Diana B. Carlin is the co-author of The 1992 Presidential Debates in Focus and The Third Agenda in U.S. Presidential Debates: DebateWatch and Viewer Reaction 1996-2004. She is professor emerita of Communication at Saint Louis University and a retired professor of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas. Through its opinion section, Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.

The post The Biden-Trump presidential debate was a disaster, but not just for obvious reasons appeared first on Kansas Reflector.