That Big Jan. 6 Supreme Court Decision Is Not the Win for Trump People Think It Is

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)

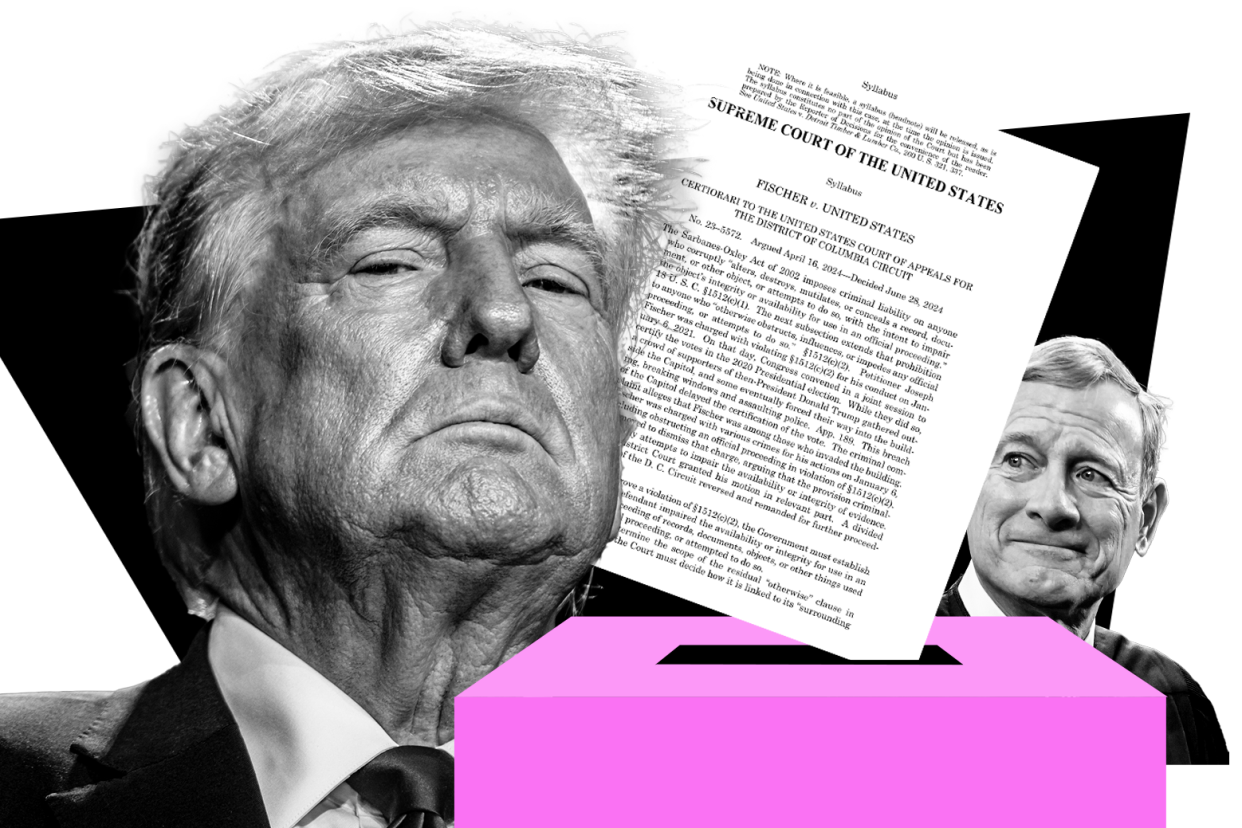

In Fischer v. United States, a divided Supreme Court, in an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, handed Donald Trump a political victory by saying the government overreached in prosecuting some of the Jan. 6 rioters. But it created a potentially big legal problem for him by confirming that the submission of “false evidence” in an official proceeding—as Trump allegedly help orchestrate with the fake electors scheme after he lost the 2020 election—indeed violates federal law. Should Donald Trump ever go to trial on 2020 election interference, and that’s a big if depending on what the Supreme Court does Monday in the pending Trump immunity case, he could well face some serious jail time.

Roberts barely acknowledged the factual circumstances surrounding the Fischer case. For months, Donald Trump had been telling his supporters that the 2020 presidential election was going to be (and eventually was) stolen from him. He encouraged his supporters to come to D.C. on Jan. 6, 2021, for “wild” protests. That was a significant day because it was when Vice President Mike Pence presided over a joint session of Congress and the Electoral College votes were to be counted confirming Joe Biden as the winner. After (and during) Trump’s speech before a boisterous crowd, large segments of that group went to the U.S. Capitol and invaded. The result was a violent insurrection, leaving five dead and 140 law enforcement officers injured. Four officers later died by suicide. It was horrendous.

Roberts sadly doesn’t acknowledge this unfortunate history and ongoing threat to American democracy or take any position on it, other than to state, contrary to the antifa takes, that “a crowd of supporters of then-President Donald Trump gathered outside the Capitol” and eventually invaded. This stands in sharp contrast with Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson who, in her concurring opinion, opened by calling out and condemning what happened:

On January 6, 2021, an angry mob stormed the United States Capitol seeking to prevent Congress from fulfilling its constitutional duty to certify the electoral votes in the 2020 Presidential election. The peaceful transfer of power is a fundamental democratic norm, and those who attempted to disrupt it in this way inflicted a deep wound on this Nation. But today’s case is not about the immorality of those acts.

Roberts instead approached the question as an antiseptic one of statutory interpretation, involving a statute concerning the “obstruction” of an official proceeding. There’s no question that the rioters could be charged with certain crimes that are straightforward, like criminal trespass or destruction of government property. Those charges will still stand against many of the Jan. 6 rioters, but the obstruction charges mattered because they raised the potential for much more jail time.

Follow me into the weeds for a moment. Here’s the obstruction statute at issue:

(c) Whoever corruptly—(1) alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or(2) otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so,shall be fined … or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

The question was whether Joseph Fischer, one of the Jan. 6 invaders, “otherwise” “obstruct[ed]” or “imped[ed]” an official proceeding. More precisely, how should the legal system read the word otherwise? Does it apply to any way in which a proceeding might be obstructed, or was it limited to doing so in ways like the ways done in (c)(1), which involves the interference or manipulation of evidence? The majority—including Jackson in her concurrence—read the statute in context to apply to doing something with evidence. Congress enacted the statute after the Enron accounting scandal, and the prime concern was about the evidence manipulation and tampering. The dissenters, led by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, read the statute more broadly to apply to all different ways one might obstruct or impede an official proceeding, including through criminal acts of trespass and violence.

Barrett is a committed textualist, and she makes a good case to read the statute broadly. But the chief justice and Jackson, a former federal public defender, had their own arguments for reading it more narrowly. As a matter of statutory interpretation, this was one of those cases that could have gone either way. My own view is that there’s no reason Congress in writing the statute would have wanted to stop obstruction or impeding of official proceedings only through the use of evidence, not violence, and that the statute was fairly applied to people like Fischer, who knew what they were doing was wrong.

So this is a political victory for the Trumpists, who can now claim judicial overreach as a number of Jan. 6 insurrectionists get part of their charges thrown out. Of course, no one is going to be getting into the weeds of statutory interpretation when they debate this in public. The point is that supporters of the rioters can say the Biden Department of Justice overreached in aggressively applying the statute. As I write this, the banner headline on the New York Times website says, “Supreme Court Says Prosecutors in Jan. 6 Case Overstepped.” That surely hands a victory to Trump and his supporters.

But Roberts did one thing that he did not have to do that surely would hurt Trump if he ever goes on trial for election interference. Trump too was charged with interfering with an official proceeding. He did not physically invade the Capitol or destroy property. He instead is alleged to have engaged in election subversion, including causing the submission of fake electors in an effort to swing the election that he lost from Biden to him.

Could that conduct count as a violation of the statute? The majority opinion states that “it is possible to violate (c)(2) by creating false evidence—rather than altering incriminating evidence.” That’s exactly what Trump is alleged to have engaged in a conspiracy to do. If Trump acted corruptly and if the fake slates of electors count as “false evidence,” well then he and others could be in a lot of criminal trouble.

Roberts’ opinion was joined by other conservative justices, including Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas. Getting them on the record on this is no small thing. And surely the Barrett dissenters would agree too that the statute covers the creation of false evidence.

That’s legally bad news for Donald Trump, should he ever go on trial. Tune in Monday to see if that’s even possible. Trump has argued that the charges against him need to be dismissed because he’s immune from prosecution. The Supreme Court is expected to issue its opinion, and I’m not expecting good news.