Bill Gates-backed Type One Energy lands massive seed extension to commercialize fusion power

Ever since a government experiment proved in 2022 that fusion isn’t as far-fetched as it once seemed, physicists, engineers, and investors have been growing increasingly bullish on the technology’s ability to deliver on its long-held — if frequently delayed — promise of providing nearly limitless amounts of emission-free power.

The latest exhibit of that exuberance is Type One Energy, which today announced a fresh $53.5 million in funding. The company had previously raised $29 million in 2023, and the current extension brings the total to around $82.5 million. Bill Gates’s Breakthrough Energy Ventures led the extension, with Australia-based Foxglove Ventures and New Zealand-based GD1 participating.

The company is betting that it can bring its fusion technology to market at a breakneck pace by leaning heavily on partners, CEO Christofer Mowry told TechCrunch. The goal is to finalize its reactor design by the end of the decade so a third party can start building it.

“Given the rate at which we want to accelerate, we needed a larger quantum of capital,” Mowry said. “We weren’t going to get there with your prototypical $20 million, $30 million, $40 million seed round.”

The other goal of the funding round, Mowry said, was to bring in partners who are more familiar with Southeast Asia, where a large portion of the world’s population lives. “In the last five years, China built more coal plants than the total installed base of North American coal plants. If we don’t find a way to decarbonize the region, we might as well fold up the tent and go home,” he said

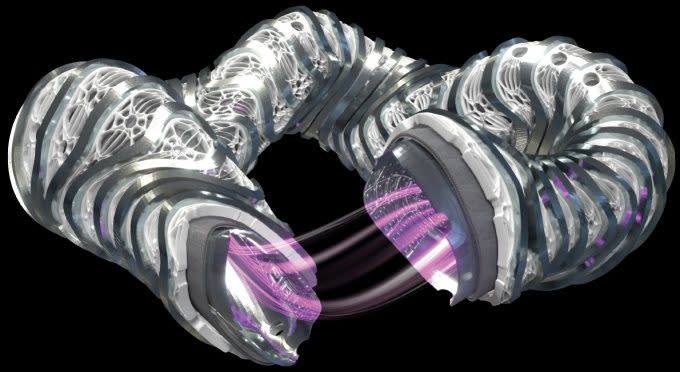

Type One’s reactor is what’s known as a stellarator, a twist on the more common tokamak design. If a tokamak looks like a doughnut, some people have described a stellarator as a cronut; it’s still a circle, but one that’s warped and bulging. The physical shape of the stellarator is defined by magnets that exert the specially shaped field that confines the super-heated plasma necessary for fusion reactions. Within the magnetic field, the plasma’s hydrogen atoms collide, fusing and releasing intense amounts of energy in the process.

The concept behind the stellarator isn’t new, but it takes a tremendous amount of computing power to fine-tune the design to make it work. The world’s largest stellarator is currently in Germany, and it can operate for minutes on end. Another operates at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where Type One was spun out.

Those projects convinced Mowry that the stellarator’s time had come, and he joined Type One early in 2023. But there was still work to do. The German stellarator known as Wendelstein 7-X is a good start, “but to turn that into a power plant, you would have to make it uneconomically large, probably four times bigger than it is,” Mowry said.

Fortunately, Wendelstein 7-X was designed over 30 years ago. Since then, computing has advanced significantly. Type One, for example, now has access to Summit, an exascale supercomputer at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, with which the startup has a partnership. Summit can perform 250 million times more calculations per second than supercomputers could back in the early 1980s, when Wendelstein 7-X was first being designed.

Thanks to Summit, Mowry said, “We can sharpen the pencil on the design.”

For the reactor magnets, Type One is using a design licensed from MIT, the same one Commonwealth Fusion Systems uses. Type One has modified the cables that make up the magnets to accommodate the twists and turns of a stellarator.

Next year, the startup wants to finalize the core reactor design. Then it’ll start building a prototype reactor called Infinity One, which will happen in tandem with the design process for a pilot reactor. Once the pilot design is finalized, which Type One hopes will happen in 2030, it’ll license it to another company to build.

“When Infinity One operates and we test it, it’s actually verifying the key design aspects of the pilot plant,” Mowry said. The goal isn’t just to prove that it works, but also to validate the assembly and maintenance of the machine.

“If you build a fusion machine, whether it's a stellarator machine or any other kind, and it takes you two years to shut it down, maintain it, start it back up, you’re gonna sell exactly none,” he said.