Block Mayor O'Connell's transit plan? It may be only way to secure much-needed MNPD reform

When News Channel 5 investigative reporter Phil Williams posted the photo of the burning cross on his social media account on Saturday, it went predictably viral. “This is a photo of an actual cross burning here in Tennessee,” he wrote on X, formerly Twitter. “Monday on @NC5 at 6 PM, I’ll have the disturbing results of my continuing investigation into the rise of hate in the Volunteer State!”

The post and ensuing report — detailing the activities of self-proclaimed Nazis, Ku Klux Klan members, and allegiants to other white supremacist hate groups — is the kind of thing that engenders near-universal condemnation. It’s hate’s lowest hanging fruit, the stuff that is easily dismissed as a relic of an uglier past. Like an echo of K. Dot on a DJ Mustard beat, civilized, progressive Nashvillians proclaim: “They not like us.”

This sentiment isn’t new. In Nashville, it goes back to at least the modern Civil Rights Movement, when racist terrorists hurled dynamite at schools and churches and the homes of Black activists. If you’d asked Nashville’s leaders then, deft as they were in their PR spins, they'd have said that those actions were the purview of more violent cities across the deep South.

In moderate Nashville, Black and white residents got along — or at least they behaved as though they did. There was no need for hoses or dogs or homemade explosives when Black folk knew not to desire too much, knew to stay in their proper places.

But this was a lie, of course. The shattered facades of attorney Z. Alexander Looby’s home and Hattie Cotton Elementary were the proof.

Hate does not always terrorize people in obvious ways

Meanwhile, when we are conditioned to react only to the extreme − to the hate that is conspicuous in its hoods and crosses that burn in the night − we miss the less prominent inequities that make life far more untenable than the occasional Nazi parade. I’m not at all diminishing the effect of this variety of virulent hate; I am, after all, the grandchild of a man born in 1931 in Centreville, Mississippi, who escaped to Kansas City to avoid the terror that yanked grown men from their beds in the middle of the night.

More often, though, the hate that currently terrorizes is in a different form. It looks like failing schools and gentrification. It looks like books bans and all-white boardrooms, even as DEI programs are being dismantled. And in Nashville as elsewhere, it looks like a police department corrupted with racism and bias, allowed to run amok.

A lot of folks in town probably wouldn’t call this hate. They’d call it unfortunate, or sad, or just the way things are. They’d say that hate is what you get from the far-right, not “progressive” leaders in a “progressive” city like Nashville.

Rissi Palmer hosts event, reminds Nashville of the Black women country music left behind

It’s why, according to Nashville Scene columnist Betsy Phillips, so many (white liberal) readers responded to her column about the ongoing mess that is the Metro Nashville Police Department — and, critically, its efforts to shirk accountability — with apathy.

“I got a lot of feedback […],” she wrote, “most of it along the lines of, ‘Well, we have to have police,’ and, ‘So you’re saying we don’t need laws or rules or …’”

Those responses are far from surprising. To those who don’t live in heavily policed neighborhoods, or who haven’t had a friend or loved one subsumed by the criminal justice system, the idea of “bad cops” is just that − an idea. It’s theoretical. Nebulous. And historically speaking, it’s often difficult for many would-be allies to jump head-first into a fight with only theory to guide them.

Black Nashvillians deserve to have their voices heard and needs met

It is entirely possible for MNPD to wreak havoc internally, amongst its own officers, and externally, among Nashville citizens, and still be considered a net positive by many − reform not required.

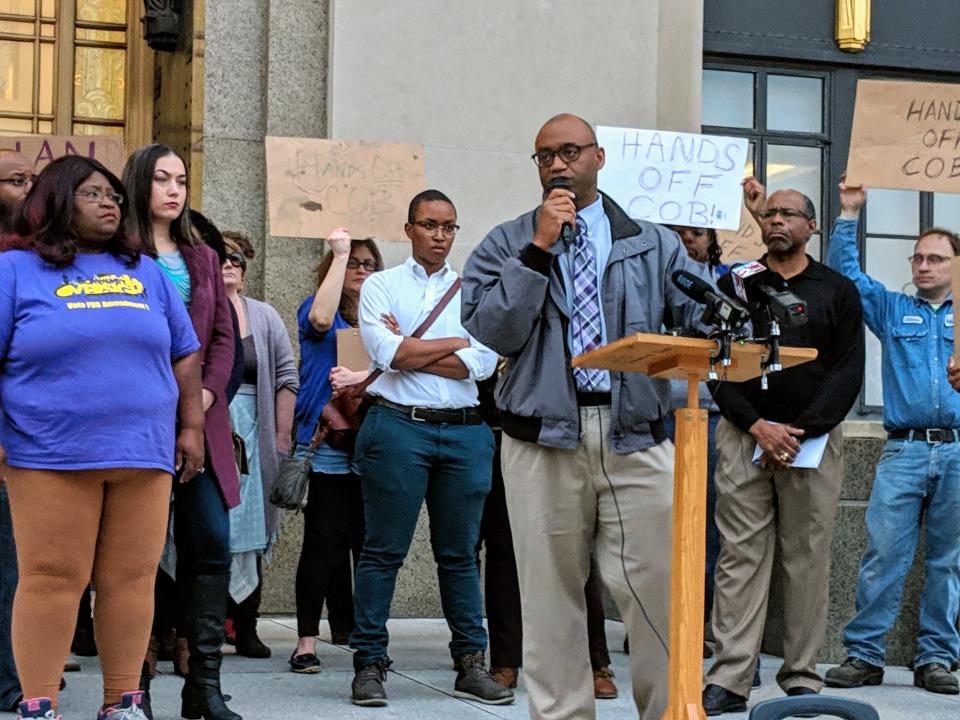

In theory, this is where Nashville Mayor Freddie O’Connell jumps in. But as Dr. Sekou Franklin, professor at Middle Tennessee University and long-time Nashville organizer, noted in an essay published by Tennessee Lookout, O'Connell's response was “lackluster." “O’Connell, I believe, understands the police department needs to change," Franklin wrote. "Yet, understanding and doing are two different realities.”

O’Connell is clearly in a tough spot. This city has a long record of Democratic mayors who won elections on the backs of votes from Black Nashvillians, but then did little to improve the material conditions of those Black Nashvillians once in office. It’s far too early to know whether O'Connell will continue in that tradition or chart his own course, but a crisis of this magnitude is a sure gauge. Ultimately, he will have to decide, like all politicians, whose needs he’s willing to fulfill − and whose he's willing to overlook.

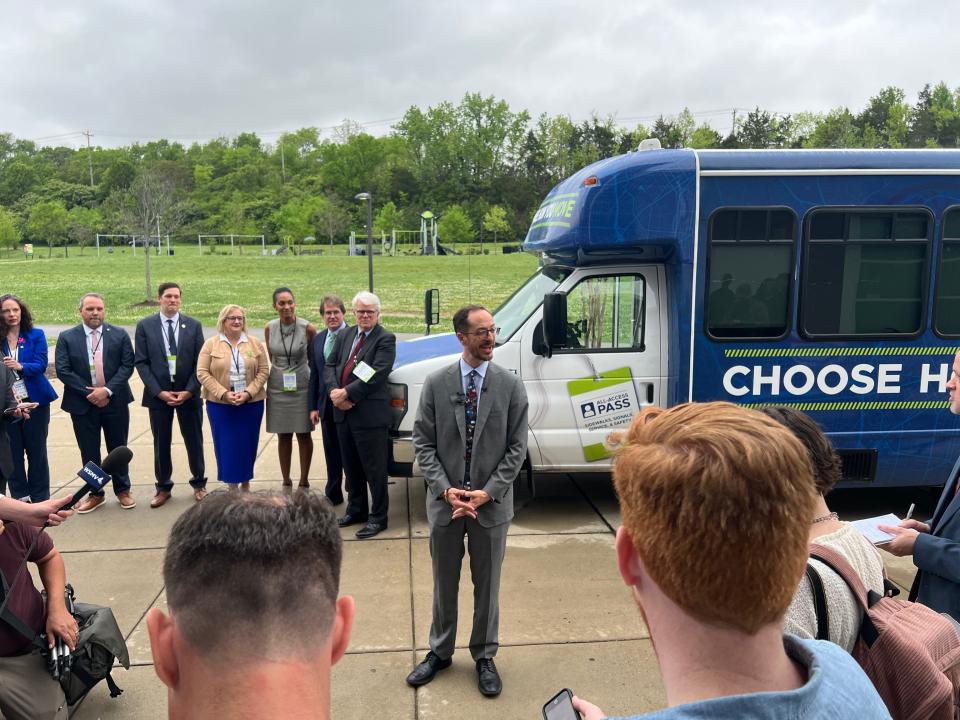

In the meantime, Nashville’s Black leaders must continue to apply the necessary pressure in hopes of affecting the change most needed in our communities. And from my vantage point, the plan to block support for O’Connell’s Choose How You Move transit plan, proposed by the Nashville NAACP and Middle Tennessee chapter of the National Action Network, seems like the smartest play.

For years, as Republicans have maintained a supermajority in the Tennessee state government, white Democrats have touted the power of the individual vote. They're right about this, of course, particularly at the local level. As it stands, the Community Oversight Board that was organized to hold the MNPD accountable was dismantled by legislators acting in the best interest (or, in this case, disinterest) of their constituents.

Rev. James Lawson fought injustice with love and nonviolence. The work is incomplete

So perhaps, while the rest of the city pats itself on the back for decrying Nazi marches and KKK fliers, Black Nashville should remined Mayor O'Connell of the interests of his constituents. And it should use the collective vote to its advantage.

Andrea Williams is an opinion columnist for The Tennessean and curator of the Black Tennessee Voices initiative. She has an extensive background covering country music, sports, race and society. Email her at adwilliams@tennessean.com or follow her on X (formerly known as Twitter) at @AndreaWillWrite.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Black Nashville's needs have long been ignored. MNPD crisis is proof