ByGone Muncie: Nitroglycerin lends new meaning to gas 'boom'

I found several crazy stories about nitroglycerin's (mis)use in East Central Indiana during the gas and oil boom of 1886-1910.

One story involves Muncie’s connection to a deadly 1910 domestic terror attack in Los Angeles. It’s all too much to include in one edition of ByGone Muncie, so I’ve separated the stories into two columns.

Nitroglycerin is a powerful explosive liquid used in demolition, combat, mining and, at one time, well drilling. It was first synthesized by Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero in 1847 and commercialized as an explosive by Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel in 1867. Nitroglycerin is the active ingredient in dynamite and smokeless powder. Curiously, the compound has also been used as a vasodilator drug for over a century.

Miners and well drillers quickly adopted nitroglycerin in the late 19th century. Compared to black powder, nitro provides many advantages. It works well in wet conditions and leaves little smoke. When powder ignites, it deflagrates — meaning the blast burns through air slower than sound at 1,100 feet per second. Nitroglycerin instead detonates, yielding a powerful explosion moving at 25,000 feet per second.

What is nitroglycerin?

Nitroglycerin is volatile, highly sensitive to shock, heat, and friction, any of which can cause unplanned detonations. For instance, transporting unstabilized quantities of nitroglycerin over rough roads in a horse cart might cause it to blow. At other times, an errant match or a flicked cigar butt would detonate it. More often than not, no one was left alive after an unplanned nitro detonation to tell what set it off.

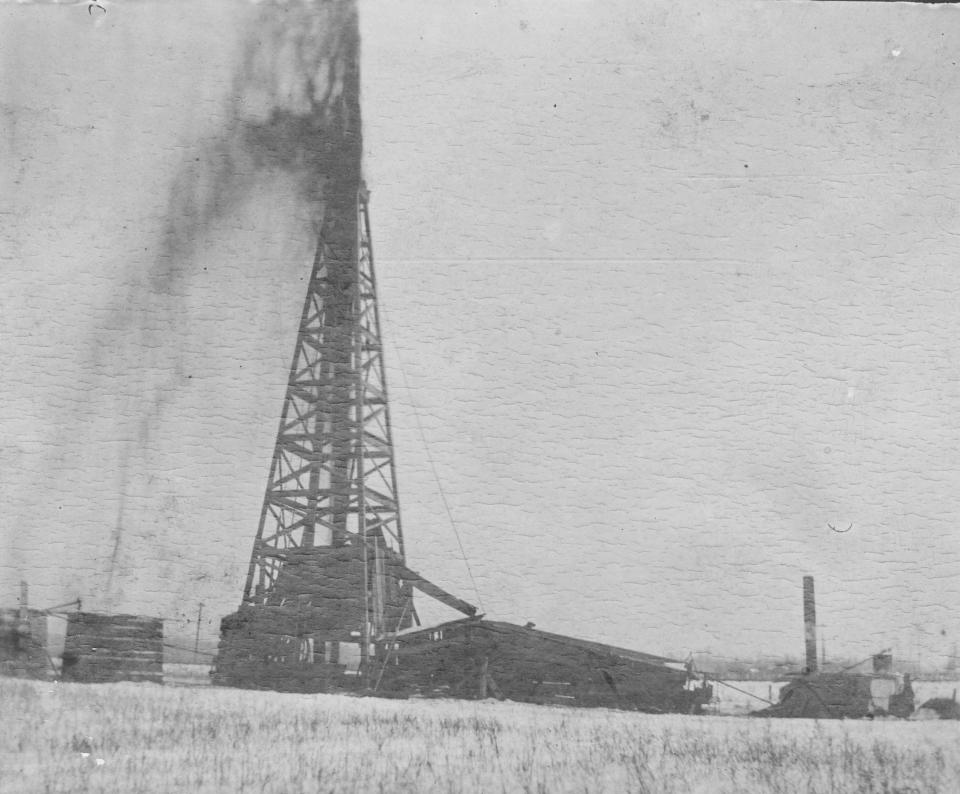

During Indiana’s gas and oil boom, nitroglycerin was used extensively to shoot wells. After the initial discovery of natural gas near Eaton in 1886, 1 trillion cubic feet was eventually found in Trenton limestone beneath East Central Indiana, along with about 1 billion barrels of oil. A productive gas field rapidly grew from western Ohio to Kokomo and from Warren and Montpelier south to Muncie, Anderson and Noblesville.

Oil in the Trenton Field was found in two pockets: in eastern Delaware County near Selma and Albany and in a band across northern Jay, Blackford and Grant counties. The latter was known informally as the Montpelier Fields, so named in honor of the nearby Blackford County boomtown.

At the time, many nitroglycerin companies like Lima Nitro-Glycerine, St. Mary’s Torpedo, Empire-American Glycerine, Independent Torpedo and DuPont Powder, manufactured, stored and transported the explosive across the region.

There was little regulation.

As a result, nitro detonations, both planned and unplanned, were frequent in the gas belt between the mid-1880s and the early 1910s.

Nitroglycerin explosions rocked entire towns

An unplanned explosion happened in the small hours of Nov. 4, 1887. The Muncie Daily Times reported, “This morning about 2 o’clock, the residents of Selma, Farmland, Winchester, Hartford City and other places were startled by a loud report, which caused the earth to tremble.” A nitroglycerin magazine had detonated on John Graham’s farm, three miles east of Muncie near Selma. Nothing was left but an 80-foot hole, “large enough to bury the Kirby House,” Muncie’s largest hotel at the time.

Three years later in March 1890, Al Barr of Lima Nitro-Glycerine set out to deliver 40 quarts of nitro to roughnecks drilling in the Montpelier Fields. Barr loaded at a company magazine in Winchester and made his way in a horse-drawn wagon toward Camden (Pennville) in Jay County. Somewhere near Stone Station, the wagon blew, obliterating it, Barr and his two horses. The explosion was heard for miles and “shook the earth,” according to the Times.

Runaway horses pull nitro wagon down the pike

In October 1899, a runaway nitroglycerin wagon careened wildly up Wheeling Pike north of Muncie. Drivers had temporarily parked the rig just past the High Street Bridge, when suddenly, something spooked the unsecured team of horses. They bolted north on the pike, violently pulling the nitro wagon behind.

At first, a few Munsonians attempted to stop the runaway, “but when they saw it was the nitro-glycerine wagon, they retreated.” Some brave unnamed farmer north of town finally got the horses under control and brought the rig back safely to Muncie.

Driver Perry Fort wasn't so lucky in February 1901. A deliverer for Empire-American Glycerine, Fort was on his way to the Montpelier Fields with a load of nitro when it detonated near Alexandria. The explosion, according to the Morning Star, threw “pieces of horseflesh into the trees.”

Hundreds of macabre locals gathered to collect souvenirs of Fort's tattered remains. One person “found a portion of his gums, in which teeth still clung.” Someone else found a small flock of dead birds not far from the blast site, “stripped clean of feathers.”

Deep human stupidity occasionally caused detonations. One breezy May day in 1896, Will Boyce and George Haley were burning trash near a small nitroglycerin shed in Boycetown, Muncie’s east-end industrial suburb. A sudden gust of wind carried hot embers onto the magazine’s roof, setting it ablaze. Boyce and Haley ran for their lives, making it to safety just before the blast. The shockwave busted windows in Boycetown and nearby Whitely.

At other times, detonations were caused by unconscionable negligence. A 15-year-old kid from Parker City named Arlie Hughes died when his baseball hit a rusty nitro canister in March 1905. The Muncie Evening Press reported, “Young Hughes was playing baseball with a number of companions when the ball struck one of the (near) empty cans” and exploded. Drillers had dumped a wagon filled with mostly spent nitro canisters a year before at the edge of the field.

In the early 1900s, massive nitroglycerin explosions rocked the gas belt. On Jan. 15, 1902, 700 quarts of nitro detonated at an Empire-American magazine east of Marion. The shockwave in turn caused 1,200 quarts to blow at the St. Mary’s Torpedo Co. shed 300 feet away. The Press reported the double-blast shockwave traveled far and “aroused half the people of Muncie. Many thought it an earthquake.”

Nitro factory obliterated

In August 1903, Empire-American’s nitro factory near Bluffton blew, killing seven workers. It was thought that 1,000 quarts of nitroglycerin detonated on site. The factory and everyone in it simply vanished, epitomizing the idiom “blown to smithereens.”

Two years later in February 1905, a whopping 2,250 quarts of nitroglycerin detonated at an Empire-American magazine near Montpelier. The resulting blast wave knocked out the region’s telephone and telegraph system.

Finally, in May 1907, an Independent Torpedo Co. magazine accidentally detonated near Albany, killing two delivery drivers. The blast was notable in that people in distant Connersville felt and heard it.

The region’s lax control of nitroglycerin led to misuse and even criminal activity. In the next column, I’ll explore how easy access inadvertently assisted with a nationwide bombing campaign in the early 1900s.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: ByGone Muncie: Nitroglycerin stories lend new meaning to gas 'boom'