Chicago Police Claim Mass Arresting DNC Protesters Are ‘Last Resort.’ What Does History Say?

Chicago is preparing to again host the Democratic National Convention in August, with police claiming that officers are trained and ready to de-escalate possible civil unrest amid anticipated protests. But with Chicago police’s documented history of violently responding to mass gatherings, activists and civil rights groups are skeptical about such a claim.

Law enforcement have long been planning for how to enforce security at the DNC, which is expected to bring tens of thousands of visitors and massive protests. Police Superintendent Larry Snelling, a veteran Chicago cop who was confirmed last year as chief, said Tuesday that officers are prepared to handle anticipated protesters and possible mass arrests.

“Make no mistake, we are ready,” Snelling said at a press conference alongside Secret Service and FBI officials. The proposed changes for how police handle mass arrests are yet to be finalized, but so far include more supervisor review onsite as well as debriefings after the event to discuss which actions were effective. Officers have also undergone new de-escalation training, with some also receiving specialized training to “respond directly to civil unrest and the possibility of riots,” according to Snelling.

“Mass arrest is a last resort,” the chief said. “But we know the realities of these types of situations, especially when the number of people we’re executing to converge upon Chicago is inevitable, that there is a possibility for vandalism. There is a possibility for violence, and we are prepared to deal with that.”

Protesters say they won’t be pushed away

Dozens of organizations have joined a coalition called “March on the DNC 2024” in an effort to protest outside the four-day convention on issues related to Israel’s U.S.-funded military campaign in Gaza, Russia’s war in Ukraine, immigration and asylum laws, police misconduct and abortion rights.

The city has denied permits for peaceful protests near the United Center, where the four-day convention will be held ― a move that has sparked lawsuits from groups, some of whom have vowed to march regardless of permit status. Protesters have said that they should be allowed to demonstrate at a distance where those attending the convention can see and hear them.

“It is the Democrats who are in power right now, and it is the Democrats who could stop this [violence in Gaza],” Hatem Abudayyeh, chair of the U.S. Palestinian Community Network, told CBS News. “This is going to be the largest protest for Palestinian rights in the history of Chicago.”

Snelling said Tuesday that not all peaceful protests are protected under the First Amendment, describing instances like blocking a roadway or protesting on private property as “crimes” that would result in peaceful demonstrations no longer having constitutional protection. The chief previously said protesters were allowed to demonstrate as long as they are peaceful.

Snelling’s comment drew ire from civil rights groups and activists like Abudayyeh, who told Block Club Chicago that Snelling’s remarks were “very serious and disconcerting.”

“The City needs a plan to accommodate free expression during the DNC this summer,” ACLU of Illinois attorney Rebecca Glenberg said in a May statement. “Instead, their approach appears to consist in denying permits and hoping for the best. Rather than make room for free speech, the City has denied multiple permit requests, authorized undefined security zones, and adopted a new mass arrest policy in time for the Convention.”

CPD’s violent history with protesters

Much of the skepticism surrounding Chicago police’s ability ― or inability ― to appropriately interact with protesters comes from the department’s decadeslong history of violently engaging with demonstrators.

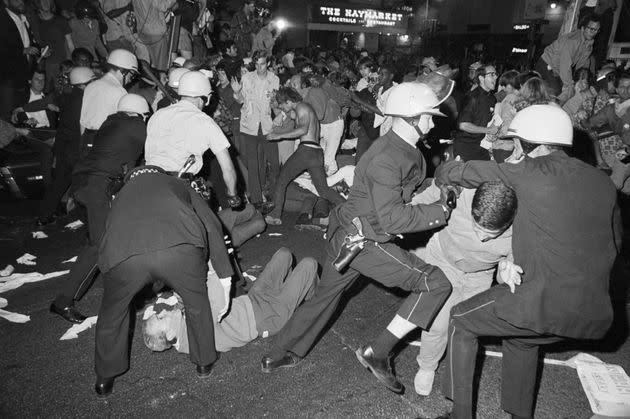

The parallels are visible when looking back at 1968, when police attacked crowds of protesters demonstrating outside the DNC in Chicago. During that year, Americans saw a major escalation in the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, and Bobby Kennedy was assassinated the night he won the California Democratic primary. The tension was high before the DNC even began.

Officers in Chicago were broadcasted beating and arresting demonstrators, leading to nearly a dozen people dead, dozens wounded and thousands detained. An anti-rioting statute that was rushed through as an amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was famously used against the Chicago Seven, a group of protesters who organized anti-war demonstrations during the 1968 DNC. A federal appeals court overturned their convictions, but did not mention the law’s constitutionality.

Federal prosecutors were encouraged to use laws like the Anti-Rioting Act against those who were protesting against police brutality in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Chicago police were found to have gravely mishandled the city’s mass protests despite having been given information ahead of time, according to a 2021 report by the city’s inspector general.

This year, police in Chicago and across the country have again highlighted the brutality by law enforcement, as nonviolent student protesters faced aggression for demonstrating against Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. Most recently, law enforcement pepper-sprayed some student protesters at the University of Chicago while the school held its graduation ceremony.

Concerns ahead of the convention

Last week, Inspector General Deborah Witzburg released a report following up on her office’s 2021 conclusions, highlighting concerns about the police department’s “insufficient training” ahead of the DNC. The watchdog report said Chicago police have improved some crowd control policies, but that those policies also included “outdated concepts” and lacked public input.

“The Department’s efforts since the 2020 protests and unrest bode for some significant improvements in the quality of its response to large-scale events, but OIG’s findings suggest that those improvements may not be realized in practice,” Witzburg wrote. “Improved plans without improved strategies for disseminating information and training on those plans may not result in improved operations. Similarly, the lack of opportunity for meaningful community engagement on the proposed policy revisions risks implementing solutions that are not responsible to public concern.”

“CPD has worked to bolster its operational planning and preparation for large-scale events, but gaps remain in the Department’s ability to effectively and uniformly communicate such plans and pursue after-action accountability. Further, CPD’s training on certain tactical responses to large crowds risks escalating crowd tensions and violating constitutional rights of lawful demonstrators,” she continued. “Draft policy provisions that do not appropriately balance the public’s constitutional right to peacefully protest nor ensure comprehensive after-action review … undercut the Department’s legitimacy and risk damage to public trust in law enforcement.”

Snelling, who was picked to be chief by progressive Mayor Brandon Johnson, rejected the inspector general’s negative findings, saying his department has made “considerable progress” when it comes to mass gatherings.

“We’re a different city. I’m a different mayor,” Johnson told The New York Times last month. “And our police department is in a much different place than it was in 1968.”