Destroying Drones Before Launch Is Becoming A Major Mission For U.S. Special Operators

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The U.S. military is concerned about its ability to defeat very high-volume drone attacks in the future, including in a large-scale conflict, such as one in the Pacific against China. So U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is now tasked with preparing to execute so-called “left-of-launch” counter-drone missions to destroy enemy uncrewed aircraft or otherwise disrupt their operations before they can leave the ground. This might involve preventing or at least hampering the production or delivery of those uncrewed aerial systems in the first place, and possibly even before a conflict erupts.

U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Sean Gainey, head of that service’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SDMC), highlighted SOCOM’s left-of-launch role during a talk the Hudson Institute think tank hosted yesterday. The threats drones pose on and off traditional battlefields are not new, as The War Zone has long highlighted. This reality has now been fully thrust into the mainstream consciousness thanks in large part to the war in Ukraine, as well as ongoing crises in and around the Red Sea and elsewhere in the Middle East. There has, in turn, been an explosion of interest in differing tiers of counter-drone capabilities in recent years, including within the U.S. military, which very much continues to play catch-up in this regard. At the same time, U.S. officials are worried about the prospect of very large groups of drones overwhelming future defenses, especially during a sustained fight.

“We’re not talking large salvos over a long distance where you can eventually attrit it as it gets there [to its intended target],” Gainey explained. “We’re looking at salvos that are [coming in from a] relatively short range distance that are… attempting to overwhelm the operator [of an air defense system].”

Gainey said the “large salvos” he was talking about here could range from tens to hundreds of drones attacking a single target or target area at once, and that they could also be layered in with other aerial threats like cruise missiles to further complicate things for defenders. Russian forces routinely subject Ukrainian cities to such drone and missile attacks. Lower-tier drone attacks, especially involving highly maneuverable first-person view (FPV) kamikaze types, occur daily on both sides of the battlefield in Ukraine, as well.

One FPV drone, one russian IFV, one epic destruction.

: Azov Brigade pic.twitter.com/ZRGqLFxwJF

— Defense of Ukraine (@DefenceU) July 12, 2024

Iran’s retaliatory attacks on Israel in April, which involved cruise and ballistic missiles, as well as drones, are another prime example of the threat picture driving the concerns the SMDC commander talked about yesterday. Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen are also currently actively engaged in drone and missile attacks on foreign warships and commercial vessels in and around the Red Sea. That group also has a long history of employing those weapons against targets on land in countries across the region, attacks that have now extended to Israel.

300+ launches.

99% interception rate.

This is the breakdown of Iran's attack last night: pic.twitter.com/aRPvxSutW2— Israel Defense Forces (@IDF) April 14, 2024

“The counter-UAS [uncrewed aerial systems] fight started as active defense… but the Secretary of Defense [Lloyd Austin] said, ‘No, we need to look holistically. SOCOM, you’re going to pick up the left-of-launch piece’,” Gainey added. “So now you have SOCOM focused on all the way up to launch and then the active defense piece with the services after launch.”

The basic fact that SOCOM has been charged with leading the left-of-launch fight against drones is not a new disclosure. Then-Maj. Gen. Gainey also highlighted to distribution of labor during a panel discussion the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank hosted in November 2023. Gainey at that time was head of the Pentagon’s Joint Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office (JCO), which was first established in 2020.

In 2022, now-retired Army Gen. Richard Clarke, then head of SOCOM, was also asked about his command’s role in left-of-launch counter-drone operations at the annual Aspen Security Forum, as The War Zone reported at the time.

Specific details are more limited about what types of missions the U.S. special operations community is currently prepared to execute, or maybe working toward being capable of performing in the future, to neutralize enemy drones before they get into the air.

“SOCOM has been designated as the left-of-launch lead for counter-UAS to get after the attack ops piece or attack the network piece,” Gainey said at the CSIS event last year. “We’re rewriting the strategy to take it from a right-of-launch – meaning, a defensive posture in how you defend against this – to incorporate more how do you get after this holistically with the right-of-launch, attack the network. So essentially, they’re looking at everything, you know, that it takes to get after holistically this UAS threat.”

Though Gainey did not further elaborate, “attack ops” here would seem to point to an obvious component of a left-of-launch strategy: destroying drones and other supporting assets like control systems on the ground. Conducting direct action raids behind the front lines to neutralize critical enemy capabilities like air defense nodes and ground-launched cruise and ballistic missiles is already firmly within the repertoire of the U.S. special operations community. There has already been clear evidence from special operations exercises in recent years that these kinds of offensive missions could also include attacking drone launch sites.

“Attack the network” is a term of art that emerged during the Global War on Terror era, especially in the context of efforts to address the threat posed by improvised explosive devices (IED). This is broadly defined as “a focused approach to understanding and operating against a well-defined type of enemy activity—such as terrorism, insurgency, and organized criminal actions—that threatens stability in the operational area and is enabled by a network of identifiable nodes and links,” according to a 2011 U.S. military handbook on the topic.

In more basic terms, this is about breaking up or otherwise disrupting networks of actors and organizations supporting a particular set of malign activities. Using the IED example, attacking the network would involve things like trying to neutralize bomb factories, as well as working to cut off the sources of funding and other resources that enable them to operate at all. U.S. forces in places like Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, together with the U.S. Intelligence Community and other elements of the U.S. government, have also used attack-the-network strategies to help counter things like arms smuggling, trade in illicit narcotics, and money laundering.

It’s not hard to see how similar tactics, techniques, and procedures might be used against the drone threat. This could still involve direct action from interdicting the delivery of uncrewed aerial systems to forward units to attacking drone production centers and related supply chains.

Special operations forces might be tasked with intelligence gathering or other indirect missions, including as part of a whole-of-government approach, parts which might be undertaken before a conflict actually erupts. In 2022, Gen. Clarke alluded to how sanctions and other efforts to restrict malign actors’ access to relevant supply chains, as well as consensus building among allies and partners about the risks of proliferation and other related issues, could be part of a left-of-launch equation.

“I think there are opportunities for our government, for our intel agencies, and our Department of Defense” when it comes to “how do we stop those drones before they even launch,” Clarke said at the time.

An unclassified 2021 white paper from the U.S. Army’s 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) offers something of a tangential example of what special operations forces might be called upon to do to support an indirect attack-the-network approach outside of an outright conflict. A fictional vignette in that document outlines a scenario in which Army Green Berets surveil an ostensibly civilian Chinese construction site in a foreign country. They then help local forces discreetly “recover” blueprints showing secret plans to enable that facility to be used for military purposes. The local government then moves to shut down the construction project. Though not expressly said, the U.S. special operations contribution to this notional operation also appears to be done covertly or clandestinely.

Specialized intelligence gathering and supporting other friendly forces engaged in similar tasks are also firmly within the U.S. special operations community’s existing mission sets.

All of this comes amid a broader discussion about how the U.S. special operations community needs to evolve as the entire U.S. military pivots to preparing for high-end fights, especially one against China, after decades of focusing on counter-terrorism and other lower-intensity operations.

There are still questions about how exactly left-of-launch operations might be executed and how effective they might be, especially against larger nation states and if applied outside of the context of a traditional conflict. Drones that Russia has been employing in Ukraine, including types sourced from Iran, as well as missiles and other systems, have been found to be packed with Western electronic components. This is despite the Russian government being currently subject to a massive array of U.S. and other international sanctions that have had pronounced impacts on the country’s economy. This underscores serious hurdles to limiting a malign actor’s access to global supply chains, in general.

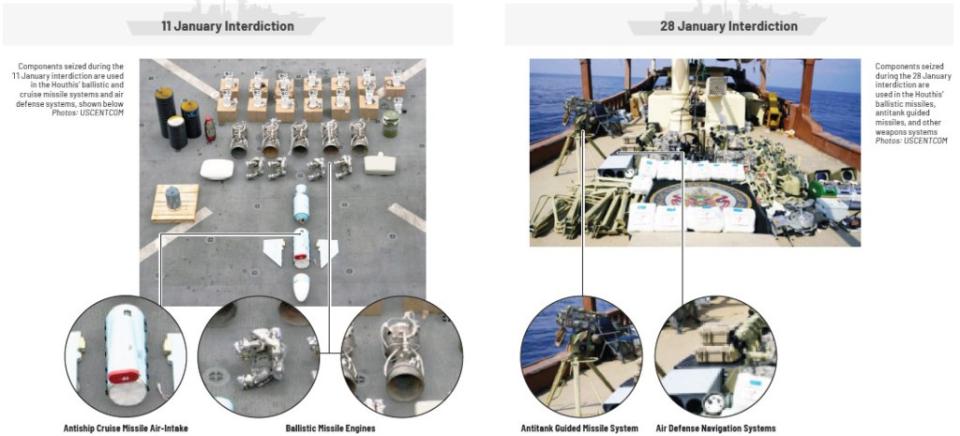

The Houthis in Yemen also continue to expand the scale and scope of their missile and drone arsenals. The complex Houthi drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabian oil infrastructure in 2019 was a particular sign of things to come, as The War Zone highlighted at the time. The Yemeni militants have been able to do all of this despite years of direct U.S.-led efforts to interdict supply chains emanating from Iran.

Regardless, “when you saw some of the last launches [like Iran’s drone and missile attacks on Israel] and the numbers that were put out there, it’s going to take a holistic, layered approach to be able to defeat those types of threats moving forward in the future,” Gen. Gainey stressed yesterday.

That holistic strategy already includes plans to have U.S. special operations forces attacking drones, as well as supporting infrastructure, supply chains, and more, before those threats get off the ground.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com