Detroit's Algiers Motel site, where 3 teens were killed in 1967, to get historical marker

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The private park where the Algiers Motel in Detroit once stood now has a Michigan historical marker, which will be introduced to the public Friday to acknowledge the police raid and tragedy that unfolded there.

The marker recognizes the role journalists have had in bringing to light what happened there. The hope, organizers said, is that it will be a record for posterity and a way to stand against police brutality and help a racially divided America come together.

"It was an incredible injustice that happened right here in Detroit that no one was held accountable for, "civil rights historian Danielle McGuire, who is writing a new book about the incident, told the Free Press this week. "A lot of times when we tell the story of the 1967 uprising, we talk about it in terms of financial cost, buildings destroyed, and the people who died that week are on a list and we don’t know anything about them."

The incident at the Woodward Avenue motel — which has been documented in newspaper reports, books and even a Hollywood film drama titled "Detroit" — led to the deaths of three Black teens, who were shot, and the injury of many others, who were beaten.

A marker dedication ceremony, which McGuire expects to be emotional for some, is scheduled from 1-2 p.m. at the site, 8301 Woodward, which is the incident's 57th anniversary.

In addition to McGuire, who now lives in Salt Lake City, Utah, event speakers include Michigan’s Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist II, Detroit’s Mayor Mike Duggan, and, potentially, survivors and relatives, of the three slain young men: Carl Cooper, Fred Temple and Aubrey Pollard.

McGuire, a former Wayne State University professor, said she worked with neighborhood residents, who wanted to know more about what happened there, to do something that would memorialize the lives lost, and in the past two years, the group settled on adding a historical marker.

'Long, hot summer'

To put the Algiers Motel shootings in context, they were just one part of the tragic, Detroit history that summer, long described as a riot and in more recent years by historians as an uprising and rebellion.

The Detroit police and fire departments, the state police and national guard and even the Army were involved, and during the five days it unfolded, there were, the Detroit Historical Society enumerated: 43 deaths, hundreds of injuries and nearly 1,700 fires and more than 7,000 arrests.

The property damage estimate: $42 million, which, in 2024 dollars would be closer to $400 million.

The historical society called it "the largest civil disturbance of 20th century America."

And more than just in Detroit, the violence, of which civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King had warned, and resulting consequence of city residents — mostly white — moving to the suburbs, was playing out in metropolitan areas nationwide.

During the summer of 1967, sometimes referred to as the "long, hot summer," more than 150 riots erupted in urban communities, often triggered, according to History, formerly known as the History Channel, by the same thing: "a dispute between Black citizens and white police officers that escalated to violence."

In June, there were riots in Atlanta, Boston, Cincinnati and Tampa, Florida, and in July, in addition to Detroit, more riots in Birmingham, Ala., Chicago, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Newark, N.J., New York, Rochester, N.Y., and Toledo, Ohio.

Examining the past

The riot in Detroit was the bloodiest of that summer.

The violence was sparked by a police raid on an unlicensed bar, known as a blind pig, and quickly escalated as the then Mayor Jerome Cavanagh called for help from then-Gov. George Romney, and President Lyndon Johnson ultimately deployed the Army's 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions.

The situation, the Detroit Historical Society later concluded, "was the culmination of decades of institutional racism and entrenched segregation."

Moreover, the deaths, which the police attempted to cover up, were exposed by Free Press journalists as more than just casualties in a firefight. Witnesses, the Free Press reported, said white officers interrogated at least two of the Black teens, them shot them at close range — and brutalized others.

In 1968, an account of the violence by Pulitzer Prize-winner John Hershey, "The Algiers Motel Incident," brought even more public attention and scrutiny to what unfolded.

And that year, a National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, often called the Kerner Commission after its chair, Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner, examined what happened releasing a 426-page report that concluded that "our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one white—separate and unequal."

The report concluded that "what the rioters appeared to be seeking was fuller participation in the social order and the material benefits enjoyed by the majority of American citizens," and suggested that "this deepening racial division is not inevitable" and " can be reversed."

In the past few years, as reports of Detroit’s bankruptcy and resurgence have emerged, more accounts of the 1967 events have been publicized, including the production and release of the movie "Detroit." The film, by Oscar-winning director Kathryn Bigelow, was released in 2017, the riot’s 50th anniversary.

It focused on the motel raid and police interrogation that killed the three unarmed teens.

The marker inscription

The motel, which was razed 1979, has been replaced by a park.

And since then, like an unmarked grave, there has been nothing at the scene to signify what happened there.

Still, in 2020, when George Floyd, a Black man, was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis, police-brutality protesters gathered at the spot, symbolically connecting the tragic events there in 1967 to what demonstrators said was still going on.

More: From 1967 to George Floyd: Detroit activists connect the dots to fight inequality

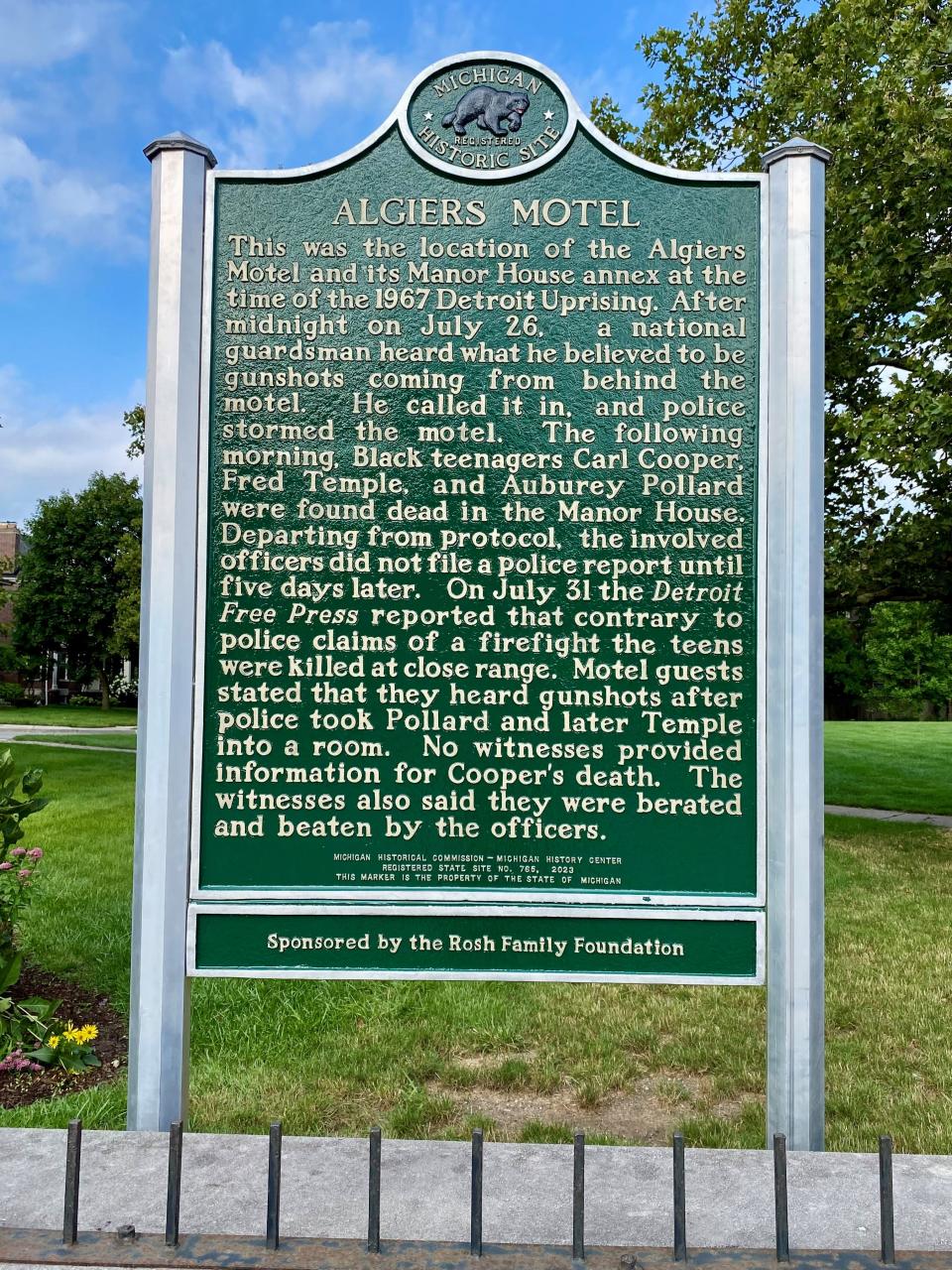

The new marker, which is visible from Woodward, reads:

"This was the location of the Algiers Motel and its Manor House annex at the time of the 1967 Detroit Uprising," and describes, how, just after midnight on July 26, a national guardsman "heard what he believed to be 6 gunshots coming from behind the motel."

The guardsman called in the gunshots, and "police stormed the motel."

The next morning, Cooper, 17; Temple, 18, and Pollard, 19, were "found dead in the Manor House," but the 13 police officers "did not file a police report until five days later," and the Detroit Free Press reported that contrary to authorities' claims of a firefight the teens "were shot at close range."

Police officers David Senak, Ronald August, and Robert Paille, were charged with murder, and in a separate federal case, the trio, along with a Black security guard, Melvin Dismukes, were accused of conspiracy to violate the civil rights of the motel guests.

The accused were acquitted by all-white juries.

Filling a void

McGuire, who credits neighborhood residents with inspiring her to study the incident and dig deeper into what happened there and underwrote much of the cost of the marker through her family’s foundation, said she has invited at least one survivor from the incident, whose memories are still raw, to attend Friday's ceremony.

She also hopes that the marker can fill a void, not just a physical one, but an emotional one, too.

"The marker is important because in the 1970s the city tore down the Algiers Motel, like so many other sites where people were killed during the 1967 uprising, and those are kind of ghost landscapes," she said. "People know that something awful happened there, but whatever happened there is met with silence — as an empty space and memory silence."

While, she said, memories of the slayings are painful to those who lived through it, those who did not, have little to connect history to the present. She said she hopes the historical marker can help preserve the past — the truth about it — and also gives the city a way to heal and, perhaps, overcome the legacy of racism.

And the marker is a reminder of the economic and human cost of inequality and injustice.

"My personal opinion," the historian said, "is that not knowing that information has made it harder for Detroit, as a city, and the people in it, to move past it, towards a more unified community. And, in larger terms, impunity for the police officers who murdered three Black teenagers that night in 1967, in lots of ways, are the taproots of today’s problems with police violence and brutality."

Contact Frank Witsil: 313-222-5022 or fwitsil@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Algiers Motel in Detroit gets historical marker