Don’t Believe John Roberts. The Supreme Court Just Made the President a King.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)

The Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority fundamentally altered American democracy on Monday, awarding the president a sweeping and novel immunity when he weaponizes the power of his office for corrupt, violent, or treasonous purposes. This near-insurmountable shield against prosecution for crimes committed while in office upends the structure of the federal government, elevating the presidency to a king-like status high above the other branches. The immediate impact of the court’s sweeping decision will be devastating enough, allowing Donald Trump to evade accountability for the most destructive and criminal efforts he took to overturn the 2020 election. But the long-term impact is even more harrowing. It is unclear, after Monday’s decision, what constitutional checks remain to stop any president from assuming dangerous and monarchical powers that are anathema to representative government. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor put it in her terrified and terrifying dissent, “the President is now a king above the law.”

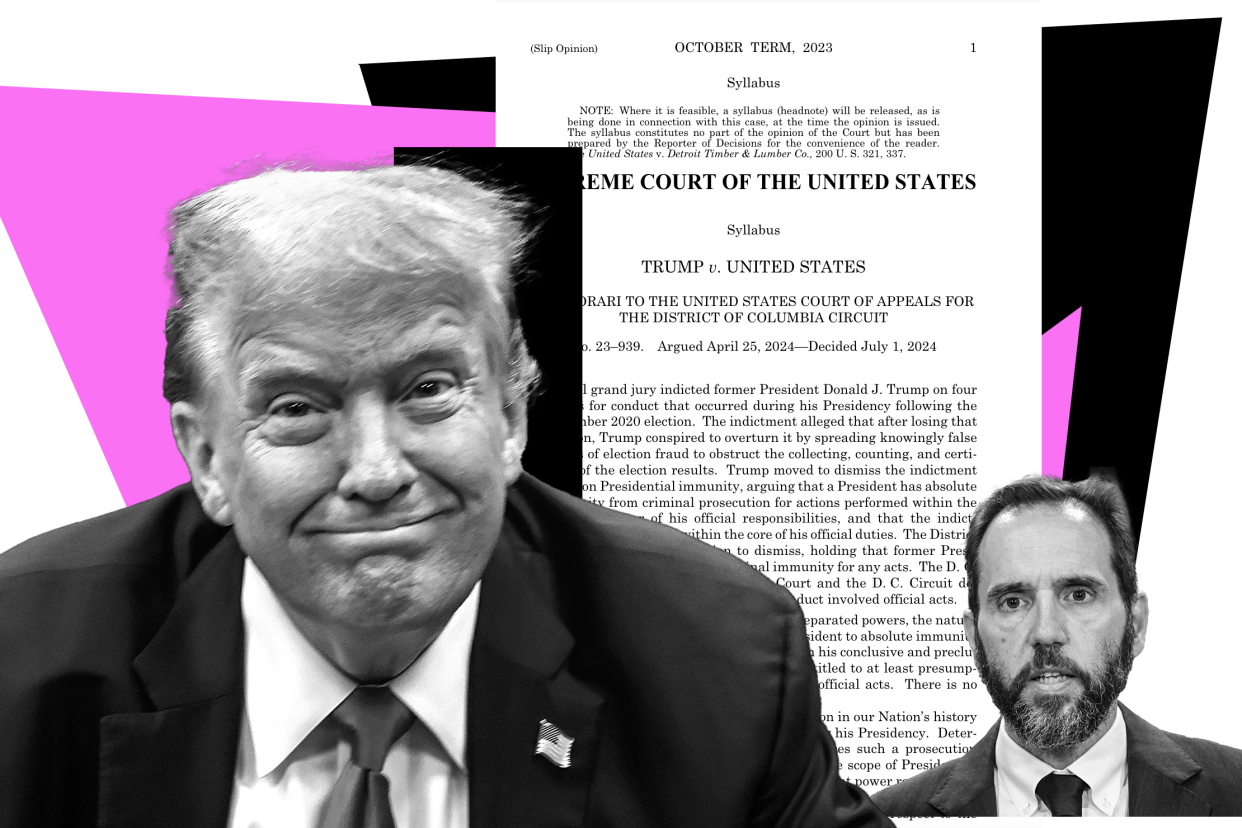

Trump v. United States, Monday’s decision, has no basis in the Constitution as written. Donald Trump brought the case as a delay tactic, an effort to run out the clock on his prosecution before the November election. Special counsel Jack Smith has charged the former president with a series of crimes related to his conspiracy to block the peaceful transition of power in 2020, culminating in the insurrection of Jan. 6. The indictment weaves a narrative of election subversion out of various actions the president took—many of which involved abuse of his office. In response, Trump raised a claim of “absolute immunity” from criminal prosecution for any “official act” he took before leaving the White House. The theory was, again, largely designed to stall the case, but also meant to shield him from the most damning charges if the case moved forward. First, the Supreme Court abetted his stalling strategy, taking up the appeal then sitting on it for months. Now it has rewarded his larger plan, too, cutting the legs from Smith’s indictment.

The fundamental problem with Trump’s legal theory is that it has absolutely no basis in the text of the Constitution, history, or tradition. The Framers knew how to grant immunity to officeholders—they did it for members of Congress—yet expressly declined to immunize the president. So Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, located this nonexistent rule in, for lack of a better word, a vibe ostensibly expressed by bits and bobs of the Constitution. His views flow from the premise that the Framers envisioned a “vigorous” and “energetic” executive who could “fearlessly” carry out his duties. Fear of criminal prosecution, Roberts warned, could interfere with “vigorous, decisive, and speedy execution” of his obligation to ensure the law is “faithfully executed.” From this hazy generalization, the chief justice extracted an atextual “absolute immunity” for any “official act” that the president takes “within his exclusive sphere of constitutional authority.” Thus, a president who accepts a million-dollar bribe in exchange for a pardon may never be criminally prosecuted, since his pardon power falls within this “exclusive sphere.”

Roberts also created, out of whole cloth, a second category of acts for which the president has “presumptive immunity,” which are at once broader and hazier. Any action that falls within “the outer perimeter of his official responsibility” now enjoys this robust immunity. How do courts know what falls within this category? They must ask if it is necessary “to enable the President to carry out his constitutional duties without undue caution.” Roberts suggested that this immunity may also be “absolute,” but “we need not decide that question today.” Rather, the lower courts will have to apply this Jell-O–style standard to the allegations in the indictment, deciding whether this immunity can be “rebutted.” Finally, the chief justice conceded that “unofficial acts” receive no immunity.

Where does that leave us? With a huge hole blown in this particular indictment and seeds sown for a future American dictator. To the first part: At the heart of Smith’s case are allegations that Trump tried to coerce the Department of Justice into interfering with the 2020 election, threatening sham investigations and wielding the agency’s powers to cow swing states into changing their results. These charges are critically important to Smith’s case; they show a president abusing the tools of his office in a desperate bid to remain in power, arguably the highest possible betrayal of the public trust. Yet Roberts declared that this coercion amounted to an “official act” that is absolutely immune from prosecution. Notably, if Trump had succeeded in using his DOJ to flip the results of the election, he would have been absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for a successful coup.

Roberts also granted presumptive immunity to many other acts in the indictment. Into this category, he placed Trump’s browbeating of Vice President Mike Pence to reject swing states’ electoral votes on Jan. 6, because he did not wish to chill the president’s ability to “discuss official matters with the Vice President” or “hinder the President’s ability to perform his constitutional functions.” Smith now bears the burden of rebutting this presumption of immunity by somehow showing that prosecution of this conduct does not pose “dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” The chief justice’s rhetoric in this passage suggests that he does not believe Smith can meet that high standard. He lumped a ton of other conduct into this category, too, including the use of his “bully pulpit” to demand the rejection of electoral votes and foment the insurrection on Jan. 6.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, may be one of the most alarming opinions in the Supreme Court’s history. Her introduction lays out the stakes:

Today’s decision to grant former Presidents criminal immunity reshapes the institution of the Presidency. It makes a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of Government, that no man is above the law. Relying on little more than its own misguided wisdom about the need for “bold and unhesitating action” by the President, the Court gives former President Trump all the immunity he asked for and more. Because our Constitution does not shield a former President from answering for criminal and treasonous acts, I dissent.

Sotomayor also rejected Roberts’ mushy hedging designed to make his opinion sound less extreme than it really is. Make no mistake, she wrote: The elements of his decision, “in effect, completely insulate Presidents from criminal liability.” The chief justice “invents immunity through brute force,” with “disastrous consequences for the Presidency and for our democracy.” His dance around “presumptive immunity” will, she warned, not prove “meaningful” in practice. As for the “unofficial” conduct that can allegedly still be prosecuted? Roberts narrows that category “almost to a nullity” by denying courts the ability to “inquire into the President’s motives.” Thus, a president may simply lie, claiming that an act was undertaken for some “official” reason, and receive near-impenetrable immunity.

Unlike Roberts, who glossed over much of Trump’s most egregious misconduct, Sotomayor dug into the sordid weeds of his scheme, explaining how it illustrates precisely the kind of conduct that merits accountability in our system. “It is not conceivable,” she wrote, “that a prosecution for these alleged efforts to overturn a presidential election” could “pose any ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.’ ” To the contrary: The Constitution demands a transition of power when a president loses reelection, and Trump illicitly sought to interfere with that process. It gets the hierarchy of constitutional values exactly backward to insulate his most corrupt acts by labeling them “official,” Sotomayor warned. The majority’s approach frees every president to manipulate his authority as a weapon against perceived enemies, with potentially lethal results. She explained:

The Court effectively creates a law-free zone around the President, upsetting the status quo that has existed since the Founding. … When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune.

Sotomayor went on:

Let the President violate the law, let him exploit the trappings of his office for personal gain, let him use his official power for evil ends. Because if he knew that he may one day face liability for breaking the law, he might not be as bold and fearless as we would like him to be.

That is the majority’s message today.

Even if these nightmare scenarios never play out, and I pray they never do, the damage has been done. The relationship between the President and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably. In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.

The justice concluded her opinion on a chilling note: “With fear for our democracy, I dissent.”

After Friday, Smith’s Jan. 6 prosecution stands on shaky ground. The district court must now spend many more months parsing the distinction between acts that are absolutely immune, almost certainly immune, and non-immune (if this final category even really exists). If a trial ever happens—which would first require Trump to lose his bid to reclaim the presidency, since his DOJ would dismantle the criminal cases against him—it will take place in the distant future; Trump will surely appeal the district court’s application of Roberts’ foggy taxonomy, and may well receive another favorable decision at SCOTUS. Beyond that, all future presidents will enter office with the knowledge that they are protected from prosecution for even the most appalling and dangerous abuses of power so long as they insist they were seeking to carry out their duties, as they understood them. (Remember, courts cannot even question their motives.) The Framers of the Constitution, wary of reestablishing the monarchy they overthrew, carefully limited the chief executive’s powers. And six justices just crowned him king.