Eroding Hilton Head beaches are getting brought back to life. Where’s all the sand going?

If all goes to plan, a $16.5 million beach renourishment project to restore eroded parts of Hilton Head Island’s shoreline could kick off as early as mid-summer next year.

Healthy, wide beaches are jewels in the crown of Hilton Head. They provide an environment for sea turtles and birds, aid in storm protection for homes and businesses, and give more space to the millions of beachgoers. But as natural erosion and strong storms chew away at the island’s shoreline, renourishing more heavily affected areas is vital in maintaining the beaches’ integrity.

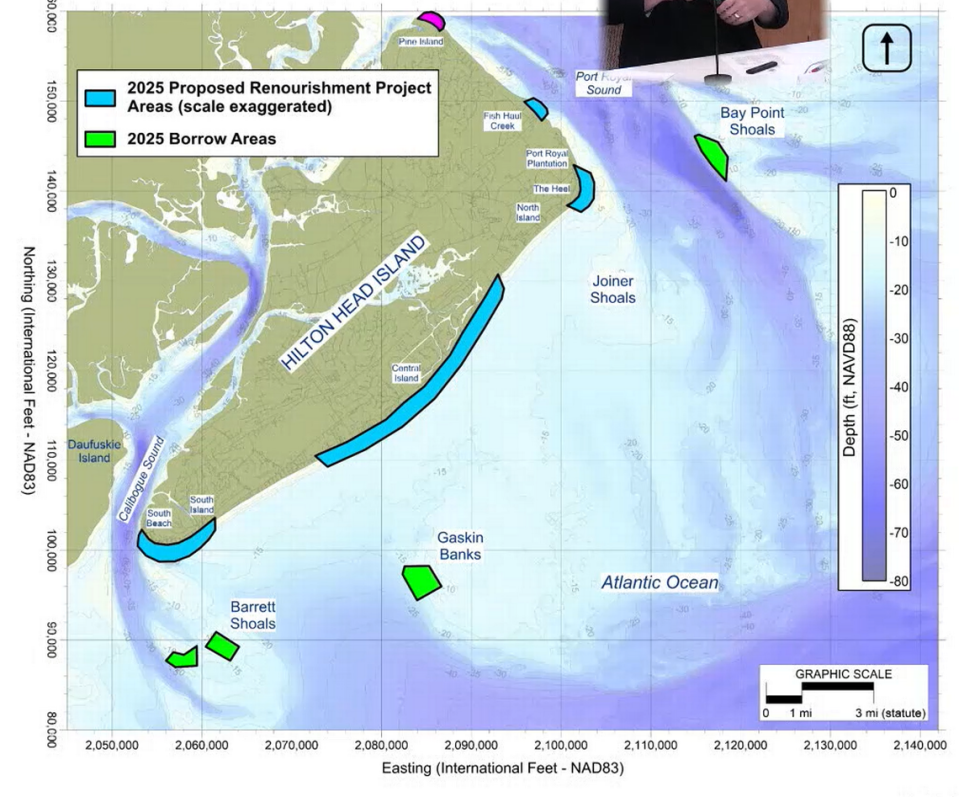

Currently in the state and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ permitting processes, the latest beach renourishment project calls for the dredging of 2 million cubic yards of sand from offshore shoals that will be funneled onto and spread across sections of the island. The undertaking is considered scheduled maintenance as part of the town’s long-standing beach monitoring program, which includes beach renourishment every eight to 10 years.

Under a rough, preliminary timeline, work would start at the northern end of the island by mid-summer 2025 and the rest of the project would start in fall 2025.

Beaches receiving sand:

South Beach

South Forest Beach

North Forest Beach

Palmetto Dunes

Singleton Beach

Port Royal Plantation

Fish Haul Creek/Park

Pine Island in Hilton Head Plantation

Gauging beach erosion

For nearly 40 years, Olsen Associates has served as the town’s coastal engineering consultant and it executed the initial restoration of the island’s shore front in 1990.

Chris Creed, the firm’s principal and vice president, said before that restoration, about half of the oceanfront was armored with seawalls and revetments. At low tide, North Forest beach didn’t have a sandy swath. Only waves crashed into a big rock wall.

“We never want it to get back to what it was in the ‘80s,” Creed said.

While unusual in its approach, Hilton Head has the “best” established beach management program, Creed said, adding that it’s “way ahead of the curve.” A 2% accommodation tax for short-term rentals goes into the town’s beach preservation. Other South Carolina town and cities, like Folly and Myrtle beaches, instead depend on state and federal funding, which doesn’t cover total costs.

The upcoming beach renourishment will be the fourth major project Hilton Head has undergone since its initial restoration 34 years ago. It comes with a $16.5 million price tag.

Nailing down which stretches of the island’s shoreline need restoring comes with decades of data and dozens of questions. Since the mid-’80s, the firm has surveyed designated locations along the entire oceanfront twice a year.

Comparing the data answers important inquiries: Are the sections eroding, stable or growing? Has the former renourishment project performed as intended? Has that sand stayed in place? Are there areas that are more stable or erosional than they were historically?

“It’s not necessarily uniform along the entire island,” Creed said. “When the dredge shows up, we want to make sure that we’re placing sand everywhere that needs it, and that there’s enough sand in those locations to provide protection over the next eight to 10 years.”

Will renourishment close beaches?

Before the dredge begins, engineers must identify a sand source that matches the existing sand’s color, size and texture.

It seems finicky, but dumping too-different sand can come with ramifications. Sand with a smaller grain size than what’s already naturally there could cause the beach to become less stable, Creed said. For Hilton Head, engineers didn’t have to look too far to find similar sand. Near the island, in the Port Royal and Calibogue sounds, there are sand shoals that source the island’s beach renourishment projects.

The hydraulic process starts when a huge dredge digs up sand from the shoal and mixes it with water. The 80% water, 20% sand mixture is then transported through a pipeline and onto the beach. When the water-sand slurry pours onto the beach, the sand falls out of suspension and piles up, and the water runs back into the ocean. Then, bulldozers shape the sand accordingly.

The upcoming project, built from dredge, will move 2 million cubic yards of sand onto the beach. For perspective, one dump truck can hold 15 cubic yards of sand. That’s over 133,000 dump trucks.

As the project begins to inch along the island’s shoreline next year, work will happen around the clock. Each day, workers will cover between 500 and 800 feet, which will temporarily close a 1,000-foot section of the beach while it undergoes construction, Creed said.

Can engineers or the town pinpoint which days active construction will be in front of someone’s private villa? No. Creed said they may know a few weeks out where the project may be, but it isn’t for certain. Weather can play a major part in the projected timeline. The town will notify the public as soon as possible, Creed said, and it will have a project map.

How about the noise? It’s an active construction site. The clamor of typical construction vehicles is a given.

But, in retrospect, beach renourishment on Hilton Head is a short-term disruption. The project may inconvenience a beachfront property for two to three days every eight to 10 years.

“We’re not responding to a storm. We’re not responding to any other catastrophic event,” Creed said. “It’s maintenance on the island’s beaches that’s necessary for a sustainable beach system.”