Feeding Our Future trial: Closing arguments overshadowed by bag of cash given to juror

The Feeding Our Future trial is being held at the Diane E. Murphy United States Courthouse in downtown Minneapolis. Photo by Max Nesterak/Minnesota Reformer.

After 24 days of testimony and arguments, jurors began deliberations Monday in the first Feeding Our Future trial, unaware that the reason one juror disappeared from their ranks was because she’d been offered a $120,000 bribe Sunday night to acquit the defendants.

The jurors also had no idea — assuming they followed the judge’s instruction not to follow media reports — that after they left the courtroom to begin debating, the defendants’ lawyers argued over whether all seven defendants should be jailed until a verdict was reached, given the attempted bribery.

The bribery attempt led the presiding judge to tighten security in the courtroom, sequester the jury, allow federal agents to seize the defendants’ cell phones and get a warrant to search them, and imprison the defendants until a verdict is reached.

The shocking turn of events came just before defense attorneys were scheduled to wrap up their closing arguments Monday. The seven defendants are accused of fraudulently getting $49 million in federal funds intended to feed children by vastly inflating the number of meals given away at 50 locations across Minnesota during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prosecutors say they used the money to buy luxury cars, houses, jewelry and property overseas — and very little food.

More than five dozen other defendants have been similarly charged and have either pleaded guilty or await trial in what’s become known as the Feeding Our Future trial, named after a nonprofit that was an alleged ringleader.

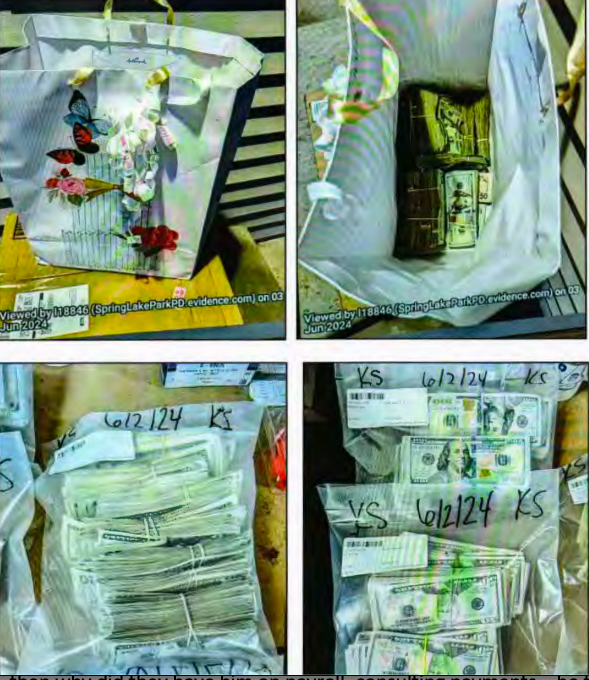

Before the last three defense attorneys began their closing arguments, and before the jury entered the courtroom, Assistant U.S. Attorney Joseph Thompson told U.S. District Judge Nancy Brasel that on Sunday night, a woman driving a Mazda left a bag with $120,000 in cash with a juror’s father-in-law and promised to bring another bag if she voted to acquit the defendants.

The juror wasn’t home at the time, and immediately notified the Spring Lake Park Police Department when she arrived to find a white Hallmark gift bag adorned with flowers and butterflies on the outside, and 20-, 50- and 100-dollar bills on the inside.

“This is outrageous behavior,” Thompson said of the bribery attempt, which has a maximum penalty of 10 years’ imprisonment. “This is stuff that happens in mob movies.”

As he explained what happened, the prosecutor noticed defendant Said Shafii Farah immediately begin typing on his phone, so Thompson asked the judge to “freeze” and let agents seize the phones as possible evidence. Brasel ordered the defendants to put their cell phones in airplane mode, and federal agents later took custody of them to “freeze the scene,” while prosecutors sought a warrant to search their contents.

According to the search warrant request, at about 8:50 p.m. Sunday, a “possibly Somali” woman “with an accent” wearing a long black dress went to the juror’s house and, using the juror’s first name, left what she called a “present” and said there would be more if the juror said “not guilty tomorrow.”

The juror, Brasel said later, was “terrified,” and excused from the jury, throwing the trial into logistical chaos. The judge had to keep the remaining 12 jurors and five alternates from hearing about the attempted bribe while also ensuring no other juror had been tampered with.

The excused juror was the only person of color on the jury (Asian-American) and at 23, the youngest.

One by one, the other jurors were brought into the courtroom, put on the stand and asked by the judge whether anyone had contacted them during the trial. Each of them said no.

After reading the jury lengthy instructions, Brasel told them she would be sequestering them during deliberations, meaning they’re not allowed to go home. She didn’t tell them why, except to say she didn’t want them to be influenced by any outside sources. They were allowed to call their family members to explain they wouldn’t be coming home, but were warned not to discuss the case with them. (By this time, media outlets were already reporting the bribery attempt.)

Brasel also had to deal with the possibility that someone in the courtroom was involved, because the only people who knew the jurors’ names were the lawyers and defendants, Thompson argued. For that reason, he argued the defendants should be jailed until a verdict is reached.

After the jury left to begin deliberations, the judge held a detention hearing in which each defendant’s attorney argued against jailing them. The defense attorneys expressed dismay at the bribe attempt, but argued the defendants shouldn’t be jailed.

Edward Sapone, attorney for defendant Abdimajid Mohamed Nur, said “someone did something reprehensible” and “whoever approached that juror with a bag of cash is not only stupid but belongs in prison.” But he said there’s no evidence his client had any connection and should be jailed, noting that his client couldn’t go anywhere if he wanted to, because he has $100 in the bank and can’t even afford to pay Sapone.

And, Sapone noted, 70 people were charged in the overall case, and so there are “lots of motives” at play.

Andrew Birrell, attorney for Abdiaziz Shafii Farah, said the bribe attempt strikes at the heart of the justice system.

“I’m horrified and shocked,” he told the judge. But, he said, “We’re Americans and we follow the law” and he saw no reason to detain the defendants.

The prosecutor emphasized the importance of maintaining judicial integrity.

“This is not a game, your honor,” he said, arguing that the incident would erode trust in the justice system. He said he hoped no other juror was approached but, “We’ll never know for sure.” He said the defendants should be jailed because “A juror was bribed. The integrity of this process is in doubt. This is the least we can do here.”

While Brasel took a break to decide what to do, a different judge had signed a search warrant allowing the defendants’ cell phones to be searched for evidence related to the bribery attempt.

So while Brasel was gone, the defendants and their attorneys crowded around the FBI agent — who has sat by prosecutors during the trial — as he ripped open evidence bags containing their seized cell phones. One by one, their attorneys gave him notes with their passwords or extended their hand to give fingerprints to allow access to the phones.

Then Brasel returned and announced that she decided to jail them all until a verdict is reached, saying she was disturbed by the fact that “there are only seven people other than attorneys who had the information to get to a juror and attempt to bribe that juror.”

“This juror was terrified,” Brasel said. “This juror remains at risk for retaliation.”

And, she added, the remaining jurors know how unusual it is that they were suddenly sequestered without warning.

“They are very concerned for themselves and their families,” Brasel said. She said if investigators narrow in on a suspect, she will revisit the decision.

Closing arguments

With that, the remaining three defense attorneys gave their closing arguments, and Thompson his final rebuttal.

Their attorneys argued the defendants did serve food and were allowed to make a profit off the program, whose rules were loosened during the pandemic. They said East Africans do business more informally, and often send money overseas. They accused state Department of Education officials and nonprofits that were supposed to oversee various vendors and nonprofits of dereliction in providing guidance to those in the program.

Andrew Garvis, a lawyer representing Aftin, said the feds didn’t stop payments until after FBI raids in January 2022, and didn’t do physical or electronic surveillance at the food distribution sites to see whether food was being distributed.

Shariff’s attorney, Andrew Mohring, also slammed federal investigators for not surveilling the food sites aside from “one drive-by at a park” and called the state education department an “administrative nightmare.” Prosecutors said they avoided surveilling a mosque where food was distributed because it’s a religious site, but Mohring said the food was distributed in the parking lot.

“They did not look,” he said.

Mohring said Shariff (unlike other defendants) didn’t spend money lavishly by buying a house, wiring money or buying a Porsche, but was largely focused on working to create an East African cultural center, Afrique, while helping distribute meals. A portion of the center was financed with federal child nutrition funds, but Shariff testified in his own defense last week that as Afrique CEO, he was not in charge of the money — deflecting to the CFO, who is not on trial yet.

“It’s OK to make money for hard work, and he worked hard,” Mohring said.

Nicole Kettwick, attorney for Hayat Mohmed Nur, said prosecutors unfairly lumped all the defendants together, even though Hayat Nur merely did clerical work for defendants, chiefly her brother, and was swept into a whirlwind.

“She was a data entry clerical person doing her job,” Kettwick said. “Hayat never became a millionaire; not even close.”

In his rebuttal, Thompson said you didn’t have to get rich to participate in the conspiracy: People have different roles and not everybody is involved in every part. Hayat Nur sent in fake rosters of children getting meals, created fake invoices and lied about meal counts, he said.

The case isn’t about whether any children were fed, but about the defendants falsely claiming they gave away 18.8 million meals in order to get $49 million in federal reimbursement.

The defendants “pointed the finger at everyone else,” Thompson said.

These seven defendants were involved in 50 food sites, but the overall 70 defendants had over 800 sites, which “moved around all the time,” Thompson said.

“What was going to be surveilled?” he asked, suggesting they would’ve had to “surveil the whole world.”

After the trial adjourned for the day, four U.S. marshals entered the courtroom and began cuffing the defendants, as their family and friends broke out in tears and disbelief. Some of the defendants were allowed to walk into the spectator section to hug family members before being taken away.

Thompson — whose parents just so happened to attend the trial, with U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger briefly sitting beside them — said after the hearing, “This never happens.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post Feeding Our Future trial: Closing arguments overshadowed by bag of cash given to juror appeared first on Minnesota Reformer.