Former police captain: I wish I’d done more to rid KCK of ‘violent people with badges’ | Opinion

Around the Kansas City, Kansas Police Department, where he spent 25 years, Michael Lee Kobe was known as T.F. Kobe, short for “That F---ing Kobe.” So what did he do to deserve this charming tag?

So much, including actually ordering the arrest of a detective who had been holding his wife and kids hostage until his son snuck out of the house and called 911. He also warned that an officer later fired for attacking a suspect was unfit to serve. Another officer who he’d argued was too violent to protect anybody wound up being convicted of rape. And in 2005 or 2006, Kobe told his commander that he’d overheard a bunch of detectives laughing that one of them had walked in on Capt. Roger Golubski having oral sex in his office.

It would not be accurate to say that nothing came of any of these efforts. But time and again, says Kobe, who retired in 2010, he’s the one who was castigated and threatened with dismissal. For doing the right thing, as I see it, though he says it was never quite that simple: “At that time in KCK, the right thing and the wrong thing were blurred.” In fact, he only agreed to go on the record if I’d promise not to portray him as “some great guy coming forward to battle everybody.”

“I could have done more,” he says, to stop Golubski, who is now awaiting a December trial on federal charges that he repeatedly raped two women, one of them beginning when she was only 13. He has also been charged with being part of a sex trafficking conspiracy. “Doing more would have entailed a great deal of risk,” Kobe told me. “I’d already tried, and it didn’t look like I was going to get any assistance from anybody.”

Michael Kobe’s experience in the KCKPD is more than a history lesson because a couple of those he accuses of protecting bad guys with badges, both in a 2021 deposition and in a long recent interview in his East Texas home, are still in positions of authority in the community.

One of those who Kobe says did not want to hear about two specific instances of misconduct is former Police Chief Rick Armstrong, now president of the Kansas City Metropolitan Crime Commission. Kobe says Armstrong threatened to fire him for reporting one officer’s criminal behavior and ignored his report of wrongdoing by a second.

I’ll go into the particulars below, but in a phone interview, Armstrong said that in his 35 1/2 years on the force, he neither protected anyone from discipline nor ever heard of a single problem involving an officer that he himself did not run to ground. He said police officers are required to live “an exemplary life,” off-duty as well as on, and are quickly disciplined if they fall short. “I did not associate with people who engaged in any questionable conduct,” he said, “even if it wasn’t expressly prohibited.” Armstrong described Kobe as someone who “didn’t get along.”

In one of the instances I asked Armstrong about, he said: “I don’t have a specific memory of what misconduct he was reporting. What I can tell you is that I disagreed with Mike Kobe frequently. Capt. Kobe had his own ideas about how he thought things should be.”

Further, Armstrong said that despite being deeply connected in the community, he never heard so much as a whisper about Golubski being involved in anything illegal or inappropriate. And if Michael Kobe did, he said, well then he’s the one at fault.

“Capt. Kobe has a responsibility. If he knows information, he has the authority to act on it. I find it so disingenuous that 25 years or 30 years after something is alleged to have occurred, if anyone knew about it and they didn’t report it, the onus is on them. They have the responsibility and they also have the liability that they didn’t act on it.”

Even now, Kobe’s report is turned back on him.

‘Roger and I are in a race to the cemetery’

I’ve been in occasional email contact with Kobe since 2021, but until recently he’d always turned down my interview requests. In May, he told me in one such message, “I’m haunted by the fact I could (should) have done more. I haven’t heard or seen any police commander express the same regret in their depositions or public comments.”

Then again, you can’t regret something that you insist never happened.

Kobe also revealed that he has Stage 4 lung cancer, and with Golubski in renal failure, “it seems Roger and I are in a race to the cemetery.” That’s not why he decided to talk to me, he says, and was if anything more of a point against it, since “I don’t want to be in my bed dying getting nasty phone calls.”

One morning in late June, I arrived at his home in Texas, where he moved after he retired, not knowing what to expect. At 76, he does not look like a man who is on hospice, but he is, and his doctors at one point told him he wouldn’t live to see July. Still, he greeted me by joking that he wished he could count on the newspaper arriving as right on schedule as I had. Then we sat at his dining room table for about three hours while he told me about his life at the KCKPD.

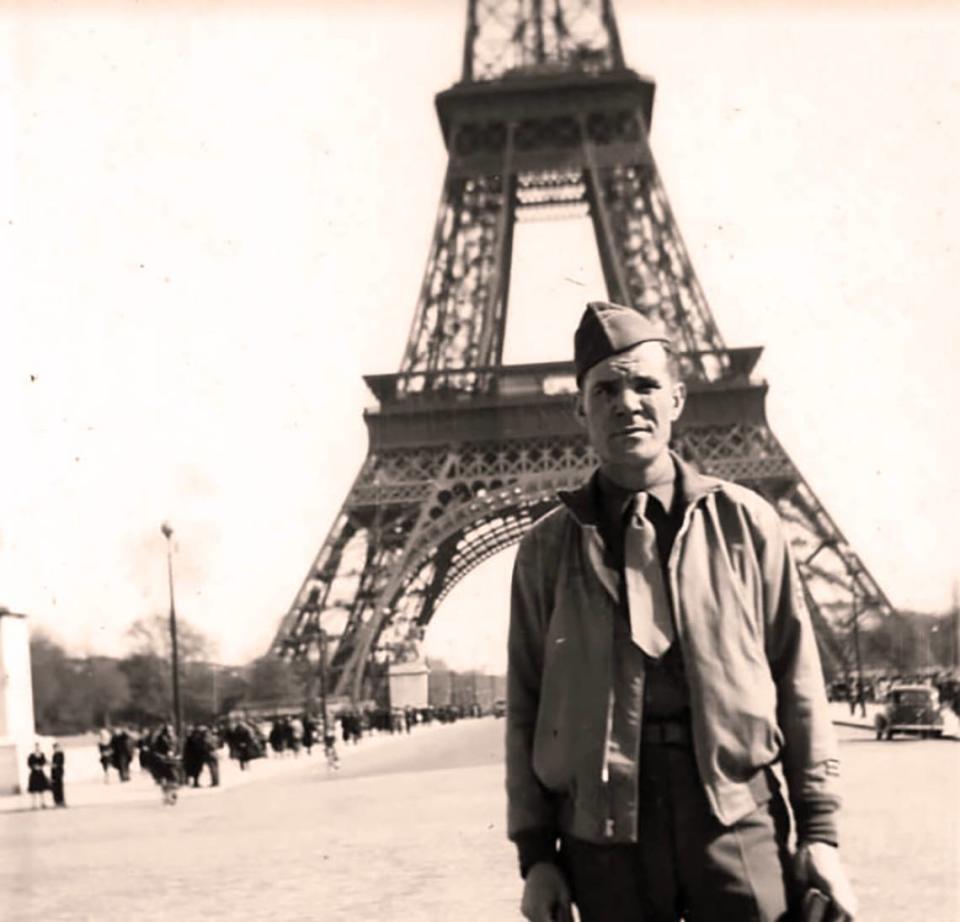

His father, John Kobe, fought in France and Germany during World War II, and Michael had already served in the Army, too, and had also been in the grocery business for years, before he joined the force in October of 1985.

He was 38 at that point, considerably older than most cadets, with a family of his own and a military sense of rectitude. “I wanted to help people,” he told me, “and broaden my insights.” He is not someone who has turned against the system.

That much is obvious on the first page of his 2021 deposition in a civil suit against the Unified Government. It was brought by Lamonte McIntyre, who was wrongly convicted and then spent 23 years in prison after Golubski and others made him the fall guy for a 1994 double murder that has officially never been solved.

‘I’m here to tell the truth’

Right away, Kobe says in that deposition that he is appearing because he was subpoenaed, and has rejected even the possibility of the counsel that might have been provided by the UG: “I believe that whether that turns out to be a good decision or a bad decision, it is the right decision.”

He also wants it on the record that he is donating the mandatory $60 fee he’ll receive for that 2021 appearance to charity, and that he is neither backing nor opposing McIntyre’s suit: “In my conversations with Mr. (Michael) Abrams,” one of McIntyre’s attorneys, “I told him that I was not on his side; I’m not on anybody’s side. I’m here to tell the truth and I believe in the system.”

When I finally met Kobe, he told me that he’d seen the fact that he was being deposed on May 12 of 2021 as confirmation of his duty to show up and tell the truth, since Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s famous “Duty, Honor, Country” speech at West Point had been delivered on May 12 of 1962.

From the very beginning of Kobe’s time on the force, the insights he broadened at the KCKPD were nothing like what he’d expected: “It was an eye-opener,” he said, when “I met some very violent people who wore badges.”

The first of those was one Richard Gorham, known as Dickie. “I was still on probation and he was a long-serving officer” — someone “I had numerous confrontations with” on calls they answered together.

‘Suspect threw his head into the flashlight’

Gorham “was often called to internal affairs. One time he came back and was laughing, saying that he had been accused of beating someone with his flashlight. … He told us at the roll call that the suspect threw his head into the flashlight! That was his explanation to internal affairs, and that floated.”

Kobe pulled Gorham off of one suspect, he says, and on another occasion was told by a man “staggering on the street” in KCK’s Armourdale neighborhood that Gorham had beaten him, too. Yet in 1986 or 1987, when he reported Gorham for beating someone else with a flashlight, the response from Kobe’s sergeant, Clarence Epson, was this, he says: “Dickie is twice the policeman you’ll ever be. You should try to be more like Dickie.”

Epson, who is 81, doesn’t remember that, he told me. But “I probably had so many discussions, I don’t remember them all.” And “none of us were perfect.” He does, he said, remember that he and Kobe “had a little problem now and then.” He also remembers “some of the trouble” with Gorham, and that he always tried to correct him.

In 1990, Richard Gorham was accused of raping a woman, and of injuring her so badly that she had to be hospitalized. And in 1992, he was convicted of raping her and was sent to prison. “I was so sad” when that attack happened, Kobe said in his deposition, “because it was all avoidable. It was very sad.”

Later, around 2000, when Kobe was the senior sergeant on the afternoon shift at South Patrol, he says, he would answer calls after his officers were already on the scene, and learn “how they were handling calls, and changed (their behavior) when I arrived.”

One patrolman he was supervising struck him as prone to violence, not because he’d ever seen him use excessive force, but because he’d come up on him out on calls being rude, aggressive and “coiled” as if ready to strike.

Yet when Kobe gave this man a harshly negative review, based on “example after example” of worrying behavior, he said his supervisor, then-Capt. Gary Wohlforth, called both him and the patrolman into a meeting — and yelled at Kobe. He also ordered him to change his evaluation, and to remove the comment that the patrolman’s prospects at the department were “grim.” Kobe told him he’d have to receive the order to change that evaluation in writing, and that order never came.

Later, after the patrolman had been fired for attacking a suspect “for no reason,” Kobe says Wohlforth told him that OK, he’d been right that one time. But Kobe had never given him any documentation, he recalls Wohlforth telling him, so what could he have done? Only, what was a review, Kobe asked, if not documentation?

No response to report of sex in police HQ

It was one day in 2005 or 2006 that Kobe says he rounded the corner to his office in police headquarters and heard a bunch of guys who worked assaults laughing about someone having walked in on Golubski getting oral sex in his office. This, too, he reported to now Maj. Wohlforth, whose response, Kobe says, was this: “Nothing. Not a word. He had the blankest look on his face.”

When I called Wohlforth, his wife answered, and said she did not think her husband would be interested in responding. Still, I sent everything Kobe said that had to do with Wohlforth to him, via the email his wife gave me, and this was his answer: “I reported everything. I did nothing wrong. I have nothing further to say.”

Kobe did not report what he had heard about Golubski being caught having sex in his office to internal affairs, and in his deposition, he said that’s because “the police department is predicated on being a paramilitary operation and the chain of command is considered very important to the success of that agency, and I believe in the chain of command and I utilized the chain of command.”

But he was troubled by Golubski’s apparent army of confidential informants, most of whom as it turned out were vulnerable Black women he’d met as victims, witnesses or suspects. Kobe did not realize that, but did wonder how it was that “we have African American officers who work or were born in the urban milieu, who went to school there, who have family and friends there” and yet not one of them had a network like that, Kobe said in his deposition.

‘They hate him because he knows who they are’

“How could a white, overweight detective be so successful at gathering together this vast network of informants who provided such vital information to so many cases?” He was also “uncomfortable,” he said, that “I had no idea how he did it because…we were not allowed to know.”

Former Police Chief Terry Zeigler, who resigned in 2019 not long after a police cadet alleged in a lawsuit that Zeigler had fired her for “exaggerated cause” after she pressed sexual battery charges against her supervisor, was asked in his 2021 deposition in the McIntyre civil case about Kobe’s allegations.

He said he had never heard anything that concerned him about his former partner Golubski, either, even though yes, he had heard “rumors” that a certain detective had walked in on him, just as Kobe had reported. “Now, nobody ever came to internal affairs to file a complaint. There is rumors all the time.”

Zeigler did want to put it on the record, though, that Kobe simply failed to understand how confidential informants worked, because he had come up as a sergeant rather than as a detective.

Former KCKPD Detective Max Seifert, who also paid a high price for doing the right thing, defended his former colleague in an interview: “Kobe was an outstanding police officer. They hate him because he knows who they are. He never fit in because the more trustworthy you are,” the more you’re considered untrustworthy.

‘He was still a loyal cop’

For a time, Kobe was the public information officer for the department, and so knew a lot of reporters, too. Former Kansas City Star reporter Mark Weibe told me he thought of Kobe as “a stand-up guy — ethical. Every once in a while, he’d tip you in a direction” toward a truth the department might not have wanted known, “but he was still a loyal cop. I respected him.”

Loyal, yes, but someone who challenged police brass as he thought necessary pretty much throughout his career. In 1996, Kobe ordered the arrest of that detective whose child had called 911 to say he was holding his family hostage. Then, as he remembers it, Maj. George Trzok, who died in 2018, angrily told him, “You don’t arrest a fine KCKPD detective! What’s the matter with you?” He stepped into the hallway to say that, too, so everyone could hear him. “And you asked me why I didn’t report Golubski” more urgently?

After that, the department instituted something informally called the “Kobe Rule,” which said that no one could arrest a fellow officer without the permission of a commander. Our understanding of domestic violence has come a long way since then, Kobe notes, and that surely would not happen today.

‘That was the total investigation’

Some time in 2006, Kobe said, then-Chief Sam Breshears replaced him as commander over homicide. And who was his replacement? Why, one Roger Golubski, who as one former UG official told me was celebrated for getting a lot of convictions. As Kobe noted in his deposition, policing is “the easiest job in the world” if you don’t play by the rules. What’s hard, he said, is doing that work while also following the law.

Around 2008, Kobe said, both Breshears and Armstrong protected Maj. John Cosgrove after Kobe reported that Cosgrove had called Detective Bill Michael to complain that “we’d solved a homicide that he wanted left unsolved.” According to Kobe, “Breshears said, ‘We asked Cosgrove and he denied it.’ That was the total investigation.”

When I reached Breshears by phone, and told him this story was about all the times Michael Kobe got in trouble for reporting misconduct, he said, “I’m really not interested in what he had to say.” I asked if he at least wanted to hear what Kobe had said that involved him. “No,” he said.

Armstrong said what is and is not considered a solved homicide is defined by federal guidelines, and he doesn’t remember anything like that ever happening.

Cosgrove said he doesn’t, either: “I’m not aware of that, “ he told me on the phone. “I’m not sure what you’re talking about. I’m not going to talk to you about this.”

He was also the lead investigator of the KCK murder for which John Keith Calvin was almost certainly wrongly convicted in 2002. He died in prison last year, though the actual triggerman had said publicly for years that Calvin was innocent. Calvin had always said that police coerced his statement. “There’s no question this is a Golubski case. A Golubski-Cosgrove case,” Calvin’s lawyer, Cheryl Pilate, told me in 2022.

Former Chief Zeigler said in his 2021 deposition that Cosgrove had at one point been disciplined for a civil rights violation — he kept interviewing a murder suspect after that suspect asked for a lawyer — and in 2014 was fired for dishonesty by then-Chief Ellen Hanson.

‘Why isn’t there a semen sample?’

The year both Kobe and Golubski retired, 2010, Armstrong threatened to fire Kobe, he says, for reporting misconduct by a different police captain. The accusations involved following and trying to intimidate a female officer he didn’t like.

Armstrong, who rightly got a lot of credit for calling in the FBI to investigate and ultimately arrest members of his own SWAT team who were stealing, says he remembers the captain but not the allegation, and never would have done any such thing.

He does recall one time a different officer was in trouble, though. When Armstrong was Kobe’s sergeant, he said, Kobe had been involved in a third negligent accident in a single year and knew that he could be fired for that. He was “very nervous that he might lose his job, and I said, ‘Mike, I don’t know why you keep banging on the chief’s door about how you think he should do things, because your career is now in his hands.’ ”

Again, Armstrong said he never heard Golubski accused of any wrongdoing, though. He believes he would have, had any criminal behavior ever occurred, and says that “to suggest that the police command staff allowed someone to behave criminally is shockingly unfair, unjust, untrue.”

So what does Armstrong make of the federal charges against the former detective, then?

Golubski’s lawyers have always said that he’s innocent of all allegations, and his superiors have said that if he did do anything wrong, they certainly never knew about it.

“What I find to be difficult,” Armstrong said, “if an individual is involved in behavior — hard evidence, that’s what’s required. We’re innocent until proven guilty. If there’s evidence, why hasn’t someone come forward? Why isn’t there a semen sample, why isn’t there a blood sample, why isn’t there a fingerprint?”

Few sexual assault cases that are reported years after the fact, for reasons that by now we should all recognize, involve semen or blood samples or fingerprints. Harvey Weinstein’s and Larry Nassar’s victims didn’t have those, either. For many victims, it would not prove lack of consent even if they did. And legally speaking, testimony is evidence.

“I believe in due process,” Armstrong said, and if a jury finds Golubski guilty, then he’ll accept that and believe that “the system has worked the way it’s supposed to.” But meanwhile, “I’ve never heard any facts that support that Roger Golubski has engaged in criminal misconduct. However, I certainly know that people, individuals, have asserted, either through stories of other people, or stories that are heard or street conversations that say that things happened.”

Those I know who have come forward, despite having been threatened and told they would not be believed, are not repeating stories that happened to other people or something they heard on the street. They are talking about their own lives. Like a lot of victims, even when the perp is not a powerful person with a badge and a gun, it took them a long time to report to authorities, though some told loved ones about these events long ago.

‘They didn’t take my complaint’

Armstrong says he has a “big heart for victims,” but if none of what they describe happened, then they are all lying.

If anything like what Golubski has been charged with actually did happen, Armstrong also asks, then where are all the internal affairs reports of complaints against him?

There were some complaints — or at least, attempted complaints — that I know about: Lamonte McIntyre’s mother Rosie McIntyre has talked under oath about her unsuccessful efforts to report that Golubski had sexually assaulted her at police headquarters in the late ‘80s. Those she spoke to in internal affairs, she said in a 2021 deposition, “said they don’t believe their officers do that, and they didn’t take my complaint.”

I’ve written before about a report by former KCKPD Sgt. Tim Hausback: “In the mid to late 1970s,” Hausback said in a 2022 deposition, also in the McIntyre civil case, “I discovered that one of my fellow KCKPD officers, Roger Golubski, was taking advantage of some of the women who worked as prostitutes.” He reported this all the way up the line and to internal affairs, too, he said, but nothing ever came of it.

When the victim in the federal case who was 13 when she says Golubski started raping her finally told her aunt what was going on — according to her deposition, which I wrote about two years ago — the girl’s aunt went straight to the police station to report Golubski. But she came back to the car convinced it was her niece who had been telling lies. “It couldn’t be true,” she said her aunt told her, “because he’d been on duty the times I said.”

I’ve also talked to and written about Tina Peterson, who worked for the Joyce H. Williams Center for domestic abuse victims in the late 1980s. In a deposition, she said that when women working on the street “described the abuse they suffered, one name came up repeatedly: Roger Golubski.” She called internal affairs twice to report him, she said, each time leaving all of her contact information and explaining exactly why she was calling. Someone would get back to her, she was told. But no one ever did.

So there were reports. But I’d like to know why there weren’t more, too, and wonder what happened to the others.

‘Truth was just as obvious 30 years ago’

I don’t see how the blurred lines between right and wrong that Kobe talks about can ever be brought into focus without the kind of reckoning that would have to include a complete review of all cases touched by Golubski.

After all this time, that review still hasn’t happened, though the Unified Government approved $1.7 million for that purpose in 2022. How’s that going, I asked Wyandotte County District Attorney Mark Dupree, and got no response. As things stand, we don’t even know how many other people were wrongly convicted, as McIntyre was, and I’m not sure we ever will.

Dupree’s conviction integrity unit only has one young part-time attorney attached to it, according to another attorney in his office. But Dupree has brought in a nationally respected outside consultant, Patricia Cummings, to advise him on innocence case procedures. And his office does finally seem to be getting ready to move forward with the first such case in the four years since KCK mailman Pete Coones was exonerated.

After serving 12 years for a murder he did not commit, on the basis of coerced testimony from a mentally ill jailhouse snitch, Coones was released in 2020. He died 108 days later, of cancer that had gone undiagnosed in Lansing.

The “new” innocence case involves Ahmon Mann, who is serving a life sentence for a 2000 murder investigated by Golubski and Zeigler, based on the now recanted testimony of a witness who says he was coerced, too.

For Mann and who knows how many others who may today be serving prison time for crimes they did not commit, what happened during the years Michael Kobe describes is not in the past at all.

As long as he’s breathing, “T.F. Kobe” will continue to be a pain in the preferred narrative. “There are a lot of people who need to be investigated, not just Golubski,” he says. “There are a lot of people they convicted wrongfully” and “the truth was just as obvious 30 years ago” as it is today.

This is still not the most popular message, and never will be. But why would Michael Kobe start going along to get along now?