Former SAVE chairman and Miami-Dade civic leader Jorge Mursuli is dead at 63

When Jorge Mursuli reflected on how civic leaders successfully campaigned to pass a Miami Dade ordinance that banned discrimination based on sexual orientation in December 1998, he recalled the importance of building bridges in the years-long process.

“When we finally presented this in front of the county commission, I think we shocked them with this parade of all these leaders, that were so amazing and so helpful,” he said in a 2019 video for an exhibition about Miami’s LGBT history. “You can’t expect people to come to you and give you what you need. You have to be able to go to the people and meet them where they’re at.”

Mursuli’s backyard held many grassroots community meetings on muggy, mosquito-infested nights. It was precisely his ability to build diverse coalitions and bring out the best in those that knew him that defines his work and legacy, said friends and colleagues.

“He has the ability to bring people from all walks of life along with him. I think that’s what made his work so important and so significant. Even more so today, in a society that is very polarized,” said Miami-Dade County Commissioner Damian Pardo.

Mursuli, 63, died on May 6 from heart failure. He is survived by his sister Evelyn Peguero, nephew Ramiro Antorcha, and niece Evy-Marie Pereira.

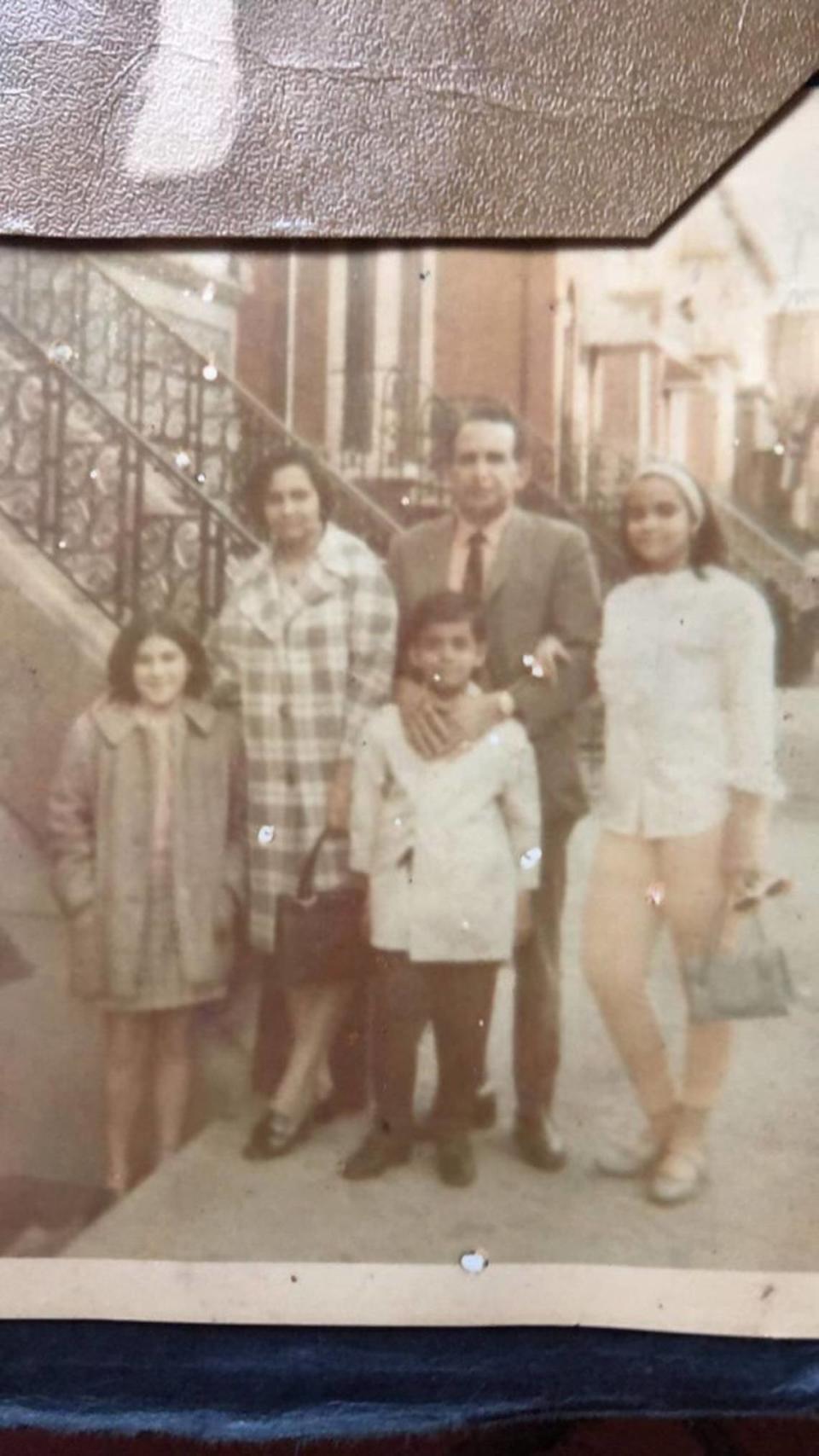

Jorge Alberto Mursuli del Valle was born in Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, on Sept. 16, 1960. He was six when his family left the island on a U.S.-bound freedom flight, his older sister told the Miami Herald. They eventually settled in West New York, N.J. Adjusting to a new country, where they did not speak the language, was difficult.

“We were the absolutely only Hispanics that they had ever seen in that school,” she said. But George, as loved ones called him, quickly picked up English. Over the years, he evolved into a popular and bright student.

A decade after first arriving, Perguero got married. Her nuclear family followed her and her new husband to Florida, a transition that was difficult for her younger brother. After graduating from Fort Lauderdale High School, Mursuli attended the University of Florida. Perguero had children, to whom Mursuli was a doting uncle, godfather, friend and advisor.

“I’m so grateful for the role that he played in the life of my kids,” Perguero said.

For Evy-Marie Pereira, Perguero’s daughter, Mursuli was a father figure who always supported her, even walking her down the aisle. She recalls how he made sure she had “the wedding of her dreams,” and the look of love he gave her when she first came out of the dressing room when trying on bridal gowns.

“He’s always shown me strength and how to be a strong, independent woman who is caring and good to people,” she said. “He definitely gave me my sense of fashion too.”

Pereira remembers how, while Mursuli worked at the Miami City Ballet, he pulled some strings so his then 8-year-old niece could present flower bouquets to the ballerinas. That’s where Mursuli met renowned dancer Jimmy Gamonet, his partner of 33 years.

“They had the best relationship ever. They complemented each other. They cared for each other, loved each other, and had fun together,” said Pardo. Gamonet died in 2021 of COVID-19 in his native Peru.

READ MORE: Choreographer Jimmy Gamonet de los Heros, who helped shape ballet in Miami, dies at 63

Despite having left Cuba at an early age, Mursuli cared deeply for his homeland, and his experiences as an immigrant informed his civic mission.

“That’s one of the reasons why he valued democracy and the ability to speak freely, and listen. He valued that so strongly because he came from exiled parents and knew what that struggle was like,” said Pardo.

Pardo recalled how Mursuli called the volunteer line of SAVE, an LGBT civil rights organization in South Florida founded in 1993, to get involved after reading Miami Herald stories that upset him. The group was advocating for county protections that would ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. A constitutional amendment campaign was ongoing to ban municipal governments from enacting those kinds of ordinances, roughly two decades after anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant had successfully lobbied local officials to repeal similar protections.

Mursuli eventually became SAVE’s chairman after Pardo and led the community in the passage of the historic human rights ordinance that banned discrimination on the basis of sexual discrimination in housing, employment, financing practices and other areas in Miami-Dade County.

“He was very smart. But he also had a high degree of emotional intelligence. He came across in such a compelling way. People wanted to listen to him,” said Katy Sorenson, a former Miami-Dade commissioner who worked with him to get the ordinance passed.

“One of his superpowers is recognizing the need for a broad coalition of people, having full inclusion and buy-in of everyone,” said Libbie Gadinsky, SAVE’s treasurer. “He was so passionate. I find his passion irresistible and I think that’s true for many of us.”

Friends also remembered Mursuli’s thoughtful, bubbly and sometimes silly personality. Pardo, the commissioner, recalled a cruise vacation they took together, some time in the fall of 2001, that was a “boatload of fun.”

“He was someone you would want to take a roller coaster ride with,” said Pardo.

Gadinsky, who met Mursuli through church, told the Herald how she would never forget the Nochebuena parties Mursuli would throw. He would have thoughtful gifts under the Christmas tree for her young children, like a painting set for her artistically inclined daughter.

“He gave us our own tradition for Christmas that we never had and included us as a family,” Gadinsky said.

Mursuli went on to become a leader in national progressive advocacy organization People for the American Way and founded Democracia USA, an organization focused on boosting Hispanic civic engagement. In 2018 he produced a program called “Democracy Lives in Me” at the Little Haiti Cultural Center, where different community members came together to discuss their shared values and stories as Americans despite political differences.

After his death, Miami-Dade leaders and officials recognized Mursuli’s significant contributions to the community. County Mayor Daniella Levine-Cava called him a “true leader who united us in the quest for equality.” County commissioners honored him with a resolution.

“The community mourns the passing, celebrates the life and will forever treasure the memory of Jorge Mursuli,” it reads.

Mursuli requested that donations be made to the Xavier Cortada Foundation, which established a memorial fund in his name.