Fresno State has 38,700 Native artifacts and remains. What’s the plan to return them? | Opinion

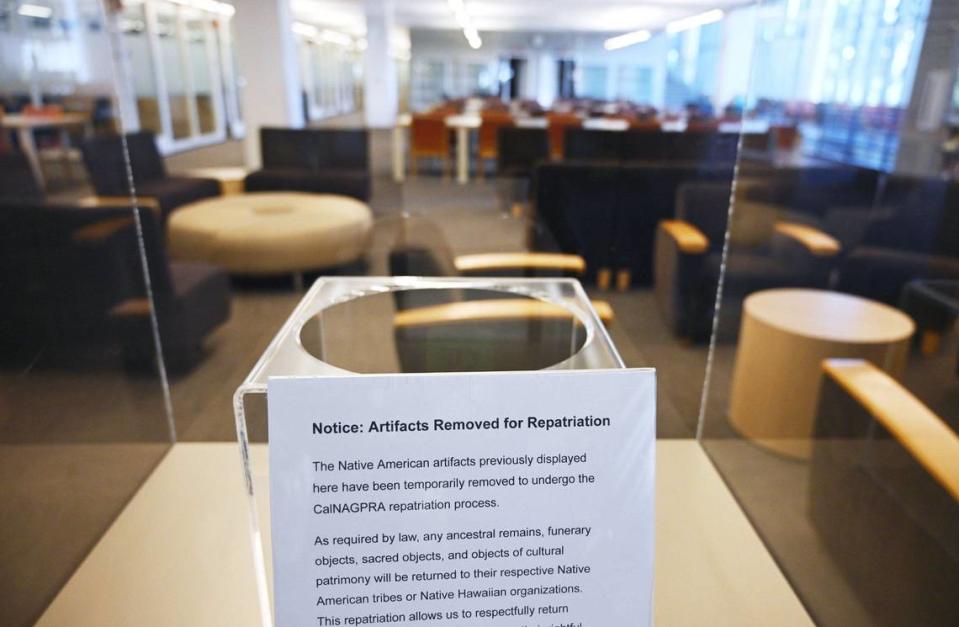

Shortly before spring break, a collection of hand-woven Native American baskets on display in the Fresno State Library disappeared quietly.

Inside the four empty display cases, placards were left informing library-goers the baskets had been “temporarily removed” so Fresno State can “undergo” a legally mandated process requiring California’s public universities to return their collections of Native cultural artifacts and skeletal remains to the tribes of origin.

These state and federal laws — specifically the California Native American Graves Protection Act of 2001 and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 – have been in place for decades. Yet a 2023 audit requested by Assemblyman James Ramos (D-San Bernardino), the Legislature’s first and only Native member, revealed Cal State University campuses had repatriated only 6% of 698,000 artifacts and human remains in their possession.

Twelve CSU schools were found to have returned 0%. That group included Fresno State, whose collection contains an estimated 38,700 cultural items as well as five complete or partial skeletons.

Opinion

Ramos responded to the audit by sponsoring AB 389, a new law that beefed up Cal NAGPRA by requiring individual CSU campuses to fund the full expense of returning their artifacts while also prohibiting their use in teaching or research without express tribal consent.

“It was designed to kick the UC and CSU in the butt and make them do something,” said Ken Hansen, a Fresno State professor of political science and American Indian studies.

The removal of the Native basket collection — they are now in the library vault — was Fresno State’s first visible step toward compliance. The second was the April hiring of Kellie Carrillo as the university’s first-ever NAGPRA coordinator.

Carrillo, an enrolled member of the Tule River Tribe, reports directly to Fresno State President Saúl Jiménez-Sandoval and works out of his office. Carrillo will soon be joined by another new hire with the job title of Director of Tribal Relations; that position is currently posted on the university’s job board.

Jiménez-Sandoval is confident the two new administrators will give Fresno State the necessary capacity to complete the repatriation process by 2027. At least that’s the goal.

The reason it will take three years is due to the size of the collection, the number of tribes involved (34 throughout California, including some that aren’t recognized by the federal government) as well as both the complexity and sensitivity of the issue.

“Our main focus has been building relationships with the tribes,” Jiménez-Sandoval said. “There is a lot of trust-building that has to be done in all of this.”

How Fresno State amassed its collection

Why does Fresno State have 38,700 Native cultural artifacts and five sets of skeletal remains stored away? The answer to that question stretches back eight decades.

Between 1950 and 1980, according to Elizabeth Lowham, dean of the College of Social Sciences, items and remains were dug up by Department of Anthropology faculty and students that participated in cultural resource management projects, often on federal or private lands. This practice stopped in 1980 but resumed between 1998 and 2023 through the department’s archeological field school and contract work.

The collection also includes numerous private donations received between 1950 and 2023. According to Lowham, the “bulk” of the 38,700 items are pieces or fragments of baskets, jewelry and pottery, sometimes as small as individual beads or shards of obsidian, rather than complete works.

Hansen, a faculty member since 2005, said records of archaeological donations tend to get hazier the farther back in time you go. During the 1960s and ‘70s, he said, farmers that discovered human bones while plowing would frequently telephone Fresno State once law enforcement determined their fields weren’t a crime scene.

“Before NAGPRA they’d just call up the university and say, ‘We don’t know what to do with this. Do you want it?’” Hansen said. “Those remains might just be accepted with little to no context.”

In 1999, Fresno State worked with several local tribes to reinter the skeletal remains of more than 150 Native people found in Fresno, Madera and Kings counties (and stored in more than 40 small boxes, according to a Bee story) during a private ceremony at Santa Rosa Rancheria near Lemoore

The five sets of remains still in the university’s possession were discovered “in older collections” during the most recent NAGPRA inventory, Lowham said.

“Returning those ancestors will be our No. 1 priority in the coming year,” Jiménez-Sandoval added. “On those we have a strong sense of where we can begin consultations and agreements with the tribes.”

Getting up to speed on NAGPRA

The actual job of engaging and consulting belongs to Carrillo, a longtime tribal administrator for the Tule River Tribe who in 2020 became the first Native elected to the Porterville City Council. She currently serves as the city’s vice mayor.

During her first weeks as NAGPRA coordinator, Carrillo familiarized herself as best she could with every aspect of Fresno State’s collection in order to be able to answer specific questions. That required numerous meetings with faculty and administrators. She also compiled an updated directory of all 34 tribes where the items and remains originated.

Last month, Jiménez-Sandoval sent each a letter that formally introduced Carrillo’s hiring, described her role and established her as their primary contact for repatriation.

“It’s a sign of respect toward the tribes: ‘We have this new position and it’s to work directly with you,’ ” Carrillo said. “Even though I’m friends with council members in a lot of these tribes I can’t just start reaching out on my own. It would be a lack of respect.”

“A handful” have responded to the president’s letter so far, Carrillo said. (Because tribes have different leadership structures, some letters had to be re-sent to ensure they got to the right person.) She has held in-person meetings with two and has “several others” in the works.

“The tribes have been very welcoming — I’ll say that,” Carrillo said. “But at the same time, this is a sensitive subject. It’s hurtful to have to even bring all this up and then have to have their community and elders involved.”

NAGPRA gives tribes the option to decline the return of their items or remains and permit Fresno State to keep them.

“I haven’t experienced that yet, and I don’t expect to,” Carrillo said. “What I will say could potentially happen is that a tribe may not have the ability to take an ancestor due to the lack of access to land. Or they need to be at a certain time so they can provide a spiritual ceremony.

“Because here’s the thing: While there are ceremonies and songs and protocols for burials, the tribes don’t have protocols or ceremonies or songs for re-burials because that’s something you would never do. You would never disrupt a burial, so having to recreate all of that is even a burden.”

Top priority for Fresno State president

The repatriation of Fresno State’s collection is a top priority for Jiménez-Sandoval — and not simply because of his heritage or that it came up on a recent performance review.

Before his family moved to Fowler when he was 10 years old, Jiménez-Sandoval grew up in a small town named Jalpa located in the mountainous Mexican state of Zacatecas. His paternal grandfather was 100% Huichol, an indigenous people of the Sierra Madres.

During Jiménez-Sandoval’s investiture ceremony in September 2022, Fresno State announced the creation of a minor in American Indian studies. He also formed a group called the Native American Leadership Council to better connect Native students and tribal leaders, and bolstered the university’s Native American Initiative with the goal of increasing the number of Native students who enroll and graduate.

“The big goal for the NALC is to really found and create a Native center at Fresno State where we would be the leading Native center in the Central Valley and showcase not just the history or the culture but really the struggles and the celebration of indigenous peoples in our region,” Jiménez-Sandoval said.

Roman Rain Tree, a community organizer with ties to the Dunlap Band of Mono Indians and the Choinumni tribe, described Fresno State’s ties to several local tribes as “frayed” but that things have improved under Jiménez-Sandoval.

“I think he gets it, but he also inherited a bleak situation,” Rain Tree said.

Bob Pennell, cultural resources director for Table Mountain Rancheria, which in 2008 gave Fresno State a $10 million donation toward the library’s expansion, declined comment about the university’s repatriation efforts. Three other local tribes did not return phone calls.

By contrast, Carrillo said her overtures have been warmly received. Still, that’s only the initial step in a long, cumbersome process, and many tribes are dealing with multiple consultation requests.

“Being honest: The tribes are going to wait and see how it goes,” Carrillo said. “I think the process is a lot, and that’s just for one university. For tribes who also have meetings with UC Berkeley and UC Davis and Sonoma State, I have to be mindful of that, too. Ensuring I’m following up but not just bombarding them because it is absolutely not a checklist for me to get this done.”