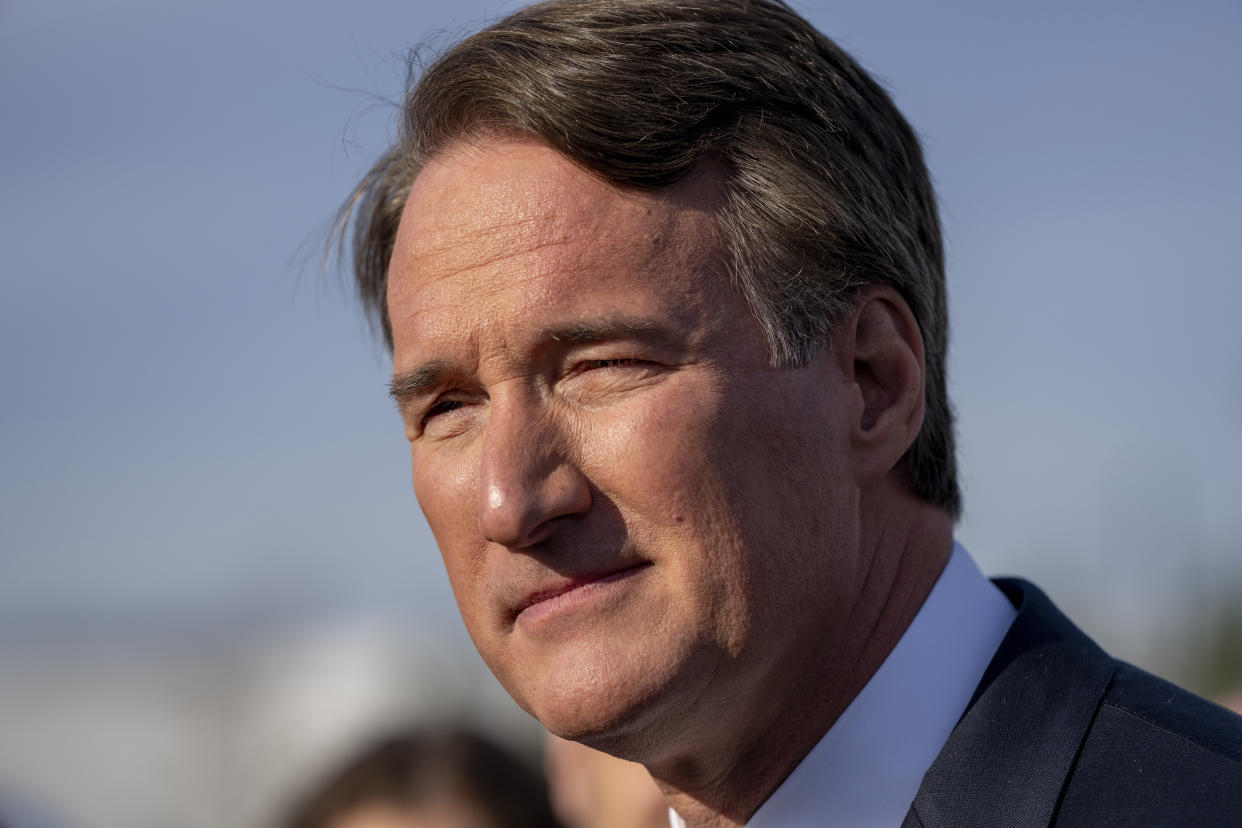

What Happened to Glenn Youngkin?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

RICHMOND, Virginia — Last summer, as Donald Trump surged and Ron DeSantis collapsed, the pleas were constant. Hardly a week went by when wealthy Republican donors, a Rupert Murdoch-owned outlet or both wouldn’t send a flare up over Virginia’s capital in hopes Gov. Glenn Youngkin would make a late entry into the GOP presidential primary.

That was then.

That was before Youngkin’s all-in effort to take full control of Virginia’s Legislature flopped, before Virginia lost the next FBI headquarters to Maryland and before Youngkin’s splashy deal to lure a new arena complex to Alexandria ended with the governor’s fellow D.C.-area dealmaker, sports owner Ted Leonsis, stating in the Washingtonian “I’m a living testament now to say it was easier, more efficient to do business in Washington, D.C., than it was in Virginia.”

And, of course, before Republican voters made clear to the party’s donor swells and Murdoch that they were quite happy, thank you very much, to nominate Trump a third consecutive time.

Now those financiers and the conservative-leaning press have made their peace, yet again, with Trump as the Republican standard-bearer. Youngkin is attempting to do the same.

He and Trump met Wednesday at the Loudoun County, Virginia, golf club that bears the former president’s name, discussing recent polling that shows Virginia potentially competitive this year. Youngkin is also appearing on Fox News to make the case for Trump rather than just criticize President Joe Biden, the preferred safe space of many elected Republicans who are uneasy with a Democratic White House but can’t advocate for a criminal defendant with a straight face.

Yet as Trump approaches a vice presidential decision in a matter of weeks, the wealthy businessman turned governor on the short list is not named Youngkin. That slot is filled by North Dakota’s Doug Burgum, who did run for president — and who also showed up in Iowa before the kickoff caucuses there to stand with Trump.

However, when the former president came to Richmond before Super Tuesday — about two months later and with the nomination effectively his — Youngkin was noticeably absent. The governor’s better option that Saturday night: Cameron Indoor Stadium for the UVa-Duke basketball game.

Trump and his top advisers were irritated by the no-show at the time and equally annoyed that Youngkin waited until after Virginia’s noncompetitive primary to endorse. And they still haven’t forgotten either snub. I was reminded as much when I asked one Trump official recently if the governor was a vice presidential prospect and got a to-the-point “no.”

Don Scott, Virginia’s Democratic House speaker, told me he spoke to Youngkin at the time. “I called him and said, ‘Thanks for at least not going to the rally,’” Scott recounted. “He just laughed, said he had other family commitments.”

Yet Republicans who are eager for Youngkin to find his way in what’s still Trump’s party believe the March episode illustrates why that may prove difficult.

“Joining the merry band of Trumpsters can’t play out when you’re the guy who takes off when Trump is in town on the eve of the primary,” said Devin O’Malley, who worked on Youngkin’s 2021 gubernatorial bid.

As O’Malley knows firsthand, navigating Trump and Trumpism has been the tension at the heart of the governor’s political identity since Youngkin emerged from the Carlyle Group boardroom to win his first campaign. It was a victory that gave Republicans of all persuasions hope just months after Trump left office in disgrace and turned over the presidency and both chambers of Congress with him. It was also a rare race in which Trump didn’t intervene in the primary and then stayed out of the general when influential Republicans successfully persuaded him not to come to Virginia before the election.

That helped Youngkin, as another of his advisers reminded me, invite voters to see what they wanted to see. Some glimpsed a mainstream, fleece-clad dad who, like them, wanted to get back to normal after Covid-19 and was a different kind of Republican from the one who just left the White House. Others caught a true conservative, devout Christian and not one of those RINOs who was a Never Trumper.

Which can be an effective way to win an election, particularly in a state that’s a bluer shade of purple. Yet it also explains why, three years later, it’s the governor of deep-red North Dakota who’s in play for vice president while Youngkin is trying to make the best of a Democratic-controlled Legislature and grasping for a legacy in one-term-and-done Virginia.

He never decided what he wanted to be. He remains torn between the main current of his party today, Trumpist grievance politics, and being the pragmatic governor of a Democratic-leaning state; between keeping his virtue intact for a future presidential primary and amassing a record to have something to sell by the time he gets to Iowa.

“It’s a fine line you have to walk,” longtime Delegate Terry Kilgore, a Republican, told me. “It’s tough.” Trying to do both is difficult, not only because of the inevitable policy tensions, but because being an effective governor with only a single four-year term takes time and commitment, particularly for a political novice.

Yet while Youngkin has been insufficiently Trumpish to please the MAGA gatekeepers, he’s also failed to forge the relationships in Richmond crucial to building a record and eventual legacy, even if it would have chiefly been breaking ground on a $2 billion sports-and-concerts Taj Mahal on the Potomac.

When I asked Kilgore what Youngkin could have done differently, the lawmaker didn’t hesitate.

“Having relationships with Democrats and some of the folks in the Legislature, we’re human beings,” he said. “People like to be — they like the governor calling them, talking to them and asking them what they think and not: ‘Here’s what I’m going to do.’”

Scott, the speaker, was even blunter about Youngkin’s failure to court State Senator L. Louise Lucas, the Democratic legislator who torpedoed the so-called Glenndome: “They thought she was invisible — I bet they see her ass now.”

Which raises the other tension within Youngkin. He won his race in part by criticizing so-called wokeness and DEI regimes. He also spent many Sundays on the campaign trail in Black churches and has made reversing the fortunes of the hard-hit, and heavily Black, city of Petersburg a personal project.

African American Democrats didn’t forget the first part, and it was always in the backdrop of the arena negotiations.

Scott, speaking about Lucas, invoked the far-right slur for DEI – Didn’t Earn It.

“This is an 80-year-old Black woman who’s been in the Legislature for 32 years, she earned her way all the way up here,” he said.

Virginia political veterans were astonished at the arena deal’s deal collapse. Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), himself a former governor, told allies he couldn’t understand why Youngkin would not have flown to northern Virginia on the state plane for the arena announcement with Scott and Lucas, the key legislators in a Democratic-controlled General Assembly, in tow, according to a person familiar with the remark.

No former Virginia governors, though, are more conversant about the challenges of landing major deals than Doug Wilder and George Allen. Wilder tried to lure the team then known as the Washington Redskins across the Potomac, steps from where Youngkin’s ill-fated arena was to be built, and Allen was in conversations with Disney about a history-focused theme park near Manassas. Neither came to fruition.

Yet Youngkin didn’t extensively engage either governor about how to maneuver with Leonsis or the Legislature for his own arena project, sources in both parties told me.

This spring I went to see Wilder, who could be called the grand old man of Virginia politics but for the fact that he’s more spry at 93 than most people are at 73.

While a Democrat, the history-making former governor has longstanding relationships in both parties and, for generations now, has caused heartburn for Democrats by being as critical of them as Republicans. Youngkin wisely courted Wilder during the 2021 campaign, but as Wilder sat in his Virginia Commonwealth University office, all manner of awards and a photo of himself and Nelson Mandela on the wall, the nation’s first elected Black governor said he had not been consulted lately.

“If I were advising him — and he has not asked me for advice,” Wilder began before I interrupted to clarify that Youngkin has not sought him out.

“No, none, none,” he said, with growing emphasis on each word.

Wilder said he heard from Youngkin when the governor wanted the former governor to join him at Allen Iverson Day in Hampton, a celebration of the former NBA star who, when he was 18, received clemency from Wilder following a brawl.

“But, no, he has never picked up the phone to call me about anything,” Wilder said.

He was unsparing in his assessment of Youngkin. “He doesn’t know Virginia politics and the Virginia governorship,” said Wilder.

Allen, a Republican, was more charitable if similarly puzzled by some of Youngkin’s moves.

Youngkin sought to use the 2023 legislative races to show that Republicans had an answer on abortion post-Dobbs, that by settling on a plan to bar the procedure after, and only after, 15 weeks they could defang Democratic attacks. And if Youngkin was successful, voila, he would have modeled an abortion strategy for the whole national party to follow.

But any talk of restrictions only aided Democrats’ strategy to talk about, well, Republican-mandated restrictions. As one longtime Virginia GOP figure told me: Democrats want to talk about abortion and Trump, why do one of those two for them?

“Gov. Youngkin understands the competition between states, that Virginia has been stagnant while our neighbors are booming, and he’s trying to turn that around,” said Allen. “He could’ve made that the centerpiece of the campaign.”

Even more perplexing to many in Virginia politics is that Youngkin didn’t make a course correction after the 2023 statehouse races, that he didn’t hire a longtime Richmond hand to make the most of his final two years in divided government.

Allen’s term in Richmond was defined by abolishing parole, reforming welfare and overhauling education standards, the same as his successor, James S. Gilmore III, was known (mostly) for cutting Virginia’s car tax.

When I asked what signature accomplishment Youngkin would be known for, Allen paused, acknowledged it was a good question and then came up with what's probably the most compelling Republican case for the governor.

“If he had not been elected, Virginia would have gone over the cliff,” Allen said, pointing to the state’s relatively low tax rate, still-standing right-to-work law and the record number of vetoes Youngkin has issued.

And, the former governor added, “Youngkin’s inauguration was the liberation of Virginia from those Covid mandates.”

Put less delicately, this is the sum of most Virginia Republicans’ view of Youngkin with about a year-and-a half left on his governorship: He’s a very nice man who has been something of a disappointment but was a needed finger in the dike in a left-turning state.

There’s something else that quietly irks Virginia’s political class about Youngkin, for which his lack of relationship-building can be a euphemism: He's a thoroughly national figure. Though reared in Tidewater, his anchorage is in Washington and the global world of high finance.

All the Fox appearances set in Virginia diners, the sloganeering and even much of his staffing does not reflect the Virginia way. Mills Godwin, the only governor who served two non-consecutive terms, once said there was “no higher honor” than being Virginia’s governor. But many in Richmond have concluded Youngkin regards it as something else: a springboard.

And yet — and yet — many Republicans think he may have good reason to view it that way.

“Big sexy is gone,” said Chris Saxman, a former GOP legislator, alluding to Youngkin’s chances for a landmark legacy. “But people like him, that’s his strength, people just like him.”

As was once said of Dwight Eisenhower, Youngkin’s smile is his philosophy.

That congeniality is why, I think, it’s too soon to write him off. As DeSantis found out the hard way, even in an ever more nationalized and polarized political world, being able to connect is crucial.

Youngkin has proven he can do so, at least with his fellow elite. A Republican who attended a small dinner last summer in Nantucket with Youngkin and a group of donors told me the room took a liking to the Virginian, even as he regaled the masters of the universe with Richmond minutiae about how he reduced wait times at the DMV.

Another GOP governor said there was not much love for Youngkin in their ranks, in part because of how he handled his rookie success. Just months after his inauguration in 2022, Youngkin hit the campaign trail for other gubernatorial candidates, bringing them his signature fleece vest and even his own soundtrack. When he cut a robocall for Brian Kemp’s reelection that the Georgia governor hadn’t asked for, well, it was all a bit presumptuous (though Kemp, like other GOP candidates, invited the Virginian to campaign with him).

However, this same governor marveled at Youngkin’s raw talent as a political athlete, recalling how he grew from initially reading his remarks at a meeting of Republican governors to barnstorming the country in the 2022 midterms. “The donor class loves him,” this governor said of Youngkin.

The looming question, for Youngkin and any less-than-MAGA 2028 aspirant, is whether actual Republican voters want sunshine, smiles and a red-fleeced grin rather than an heir to the red-necktied scowl.

“He’s about the politics of addition not subtraction,” Henry Barbour, an RNC committeeman from Mississippi, said of Youngkin.

By 2028, Barbour said, “Youngkin could be a positive force for change” by which point the “extreme wings of both parties will have overplayed their hand.”

I’m more skeptical that Republicans will make a turn away from Trump (and Trumpism) if he finishes his second term, no matter the amount of donor wishcasting.

Should the former president lose this fall, though, there may be an opening for a different sort of Republican in 2028, one who doesn’t necessarily reject Trump but who has a notably different identity. Ring a bell?

First, though, Youngkin, whose job approval has remained above 50 percent despite his setbacks, will have to fend off the coming wave of Senate Republican recruiters.

The governor’s allies insist up and down he has no interest in running for the Senate in 2026, the year Youngkin’s term expires. But I’ve lost count of how many governors became easier prey for the NRSC and DSCC once they left office, lost their State Police detail and didn’t have a next gig.

Youngkin will be wooed and perhaps tempted, particularly if Biden wins and Virginia is decided by five or fewer points this year. Nobody knows this better than Warner, who’s the senator up in 2026. He lived through a similar near-death political experience in 2014 when he pulled out a closer-than-expected win in the second midterm of another Democratic president. Warner has been particularly attentive, Virginia Democrats point out to me, in maintaining a warm relationship with Youngkin.

Scott said it would be clearer now if Youngkin was interested in Warner’s seat.

“If he were running for the Senate in Virginia, he would not have been so extreme on guns and abortion,” said the House speaker.

Youngkin is the rare self-funding Republican businessman who didn’t have to be coached by advisers on cultural conservatism. He actually believes the stuff, at least on abortion and his personal faith. The most revealing Youngkin anecdote may be the one I heard from a Northern Virginia businessman who attended a small breakfast with the governor and was struck that the governor wanted to say grace with a group of largely Jewish executives.

Youngkin, though, is also a businessman to his core. The word that invariably comes up talking to people who know him is: optionality. It’s also the word that came to mind when I saw the picture from their meeting this week of Youngkin and Trump, the former president flashing an I-got-him smile and thumbs up.

It was a reminder that the more likely step forward for Youngkin would be to improve his standing with Trump and vie for a cabinet post should the former president win in November. O’Malley, the former Youngkin adviser, said the governor would make an ideal Treasury secretary because of his knowledge of markets and ability to drive a public message.

And there are some in Trump’s orbit who tell me Youngkin could have a role in the administration, even if vice president isn’t on the table.

What’s for certain to many of those who know Youngkin, though, is that there’s an end goal.

Scott told me that when he attended the Kennedy Center Honors late last year with Warner, the two encountered David Rubenstein, the former Carlyle Group CEO who worked with Youngkin at the private equity firm.

Rubenstein, Scott recalled, said Youngkin is focused on one objective: becoming president.

Ben Johansen contributed to this report.