Google accused of misleading consumers to grab more data for ads

Italy's competition and consumer watchdog has announced an investigation into how Google gets users' consent in order to link their activity across different services for ad profiling, saying it suspects the adtech giant of "unfair commercial practices."

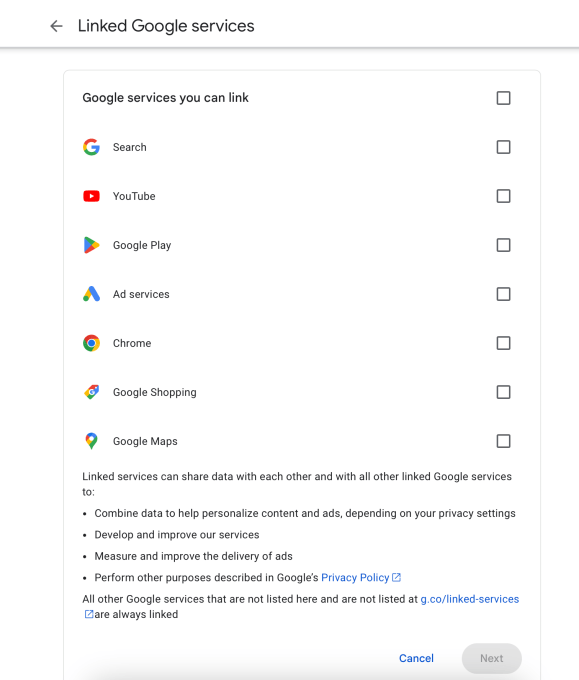

At issue here is how Google obtains consent from users in the European Union to link their activity across its apps and services — like Google Search, YouTube, Chrome and Maps. Linking user activity lets it profile them for ad targeting, the company's main source of revenue.

In response to the Italian AGCM's investigation, a Google spokesperson told TechCrunch, "We will analyze the details of this case and will work cooperatively with the Authority."

Since early March, Google has been subject to the EU's Digital Markets Act (DMA), an ex-ante competition regime that applies across the European Union, including in Italy. The company is one of several designated internet "gatekeepers" that own and operate a number of major platforms (aka "core platform services"), as are Meta, X, Amazon, ByteDance and Microsoft.

The pan-EU regulation is relevant to Italy's investigation of Google, since the DMA has made it mandatory for these gatekeepers to obtain consent before they can process users' personal data for advertising, or to combine their data harvested from across their services. The AGCM's probe appears to be focused on the latter area.

"[T]he request for consent that Google submits to its users to the linking of the services offered may constitute a misleading and aggressive commercial practice," the AGCM wrote in a press release.

"Indeed, it appears to be accompanied by inadequate, incomplete and misleading information and it could influence the choice of whether and to what extent consent should be given."

The regulator's action is interesting, since it is typically the European Commission that leads enforcement against these gatekeepers. However, the EC's ongoing investigation of Google under the DMA, announced back in March, does not focus on whether it gets consent for linking user data. The EC has said its DMA probe concerns self-preferencing in Google search; and anti-steering in Google Play.

The Italian authority looks to be taking the opportunity to act on concerns the Commission has yet to get around to.

Competition enforcement in the EU and across member states generally aims to avoid duplicating effort, but in this case, it may be that the Italian regulator is picking up the slack.

A Commission spokesperson told TechCrunch it "takes note" of the AGCM investigation into consumer choices implemented by Google in relation to its obligations under the DMA, adding: "The investigation complements enforcement work under the DMA. In implementing the DMA, gatekeepers have to comply with other relevant EU and national rules, including but not limited to consumer protection and data protection rules."

Google's consent flow under the lens

In its press release, the AGCM said it is concerned that Google's request to users seeking their consent does not provide them with the information necessary to make a free and informed choice. And when it does, Google provides information "inadequately and imprecisely," the AGCM said. Specifically, the regulator suspects Google is not being transparent about "the real effect" on users when they consent to their accounts being linked.

Additionally, the regulator suspects Google isn't being open about the full picture. It is worried about the level of information Google provides "with respect to the variety and number of Google’s services for which 'combination' and 'cross-use' of personal data may occur, and with respect to the possibility of modulating (and thus limiting) consent to only some services."

The DMA states that consent for linking accounts for advertising purposes must comply with standards set out in another pan-EU law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which stipulates that consent must be "freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous."

The GDPR also sets conditions on how consent can be sought through written statements in an online interface. It requires such requests to be "presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from the other matters, in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language."

While data protection authorities usually lead on enforcement of the GDPR, the DMA's incorporation of the former's consent standards by reference leads to what we see here: Italy's competition and consumer watchdog scrutinizing Google's consent flow.

As well as worrying about the information that Google provides users, the AGCM is concerned about how Google is asking people for their consent. That suggests the "techniques and methods" it is using for requesting consent could be a problem, too.

The authority said it suspects Google's consent flow "could condition the freedom of choice of the average consumer," leading to users being "induced to take a commercial decision that he/she would not have taken otherwise, by consenting to the combination and cross-use of his/her personal data among the plurality of services offered." Or, in fewer words: Google might be manipulating people to agree to link their accounts.

Manipulative or so-called "dark pattern" design has been an unfortunate feature of online choice flows for years across all sorts of consumer services. But increasing regulation of digital platforms and services in the EU looks to be challenging the user-hostile tactic at long last.

As well as the DMA referencing GDPR standards for consent, enabling more enforcement bodies to scrutinize choice flows, the bloc's Digital Services Act (DSA) outright bans the use of design that uses deception or other types of underhanded nudges to distort or impair users' ability to make free choices.

Just last week, the EU confirmed its first preliminary findings of a breach of the DSA's rules against deceptive design, when it announced that it suspects the blue check system on X (formerly Twitter) of being an illegal dark pattern.

This report was updated with comment from the Commission