He's served ⅓ of his life in prison for someone else killing his cousin; that's felony murder

Editor’s note: This story is the result of a months-long investigation by Yale journalism student Madison Hahamy, in collaboration with the Yale Investigative Reporting Lab. This project accompanies reporting on felony murder by Sarah Stillman for the New Yorker, which was recently the recipient of a 2024 Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting for demonstrating “our legal system's reliance on the felony murder charge and its disparate consequences, often devastating for communities of color." The Lab's reporting team has obtained original public records on felony murder cases in more than a dozen states, interviewed family members and spoken with legal experts.

Deante Dalton made it only a few minutes into his first class of the day at Elkhart Memorial High School, junior English, before clutching his stomach and asking if he could go to the nurse’s office. When he reached the nurse, he called his mom, Nakia Dalton, to ask if she could pick him up, and she arrived moments later. They left the front office, exited the school, and were steps from the car when the teen stopped and told her he thought the police were coming to arrest him.

At that very moment, the Daltons recall, police from inside and outside of the school converged and threw him against a car as his classmates watched from the window.

“They took my baby from school,” Nakia Dalton said. “And I was crying so hard that I didn’t know if I was coming or going.”

Deante Dalton was 16 when he was arrested on Sept. 11, 2014, and charged with felony murder, a legal doctrine that allows prosecutors to charge a person with murder if someone dies while the defendant is carrying out certain other non-murder felonies. In Dalton’s case, prosecutors alleged he and two young men — his cousin Dretarrius Rodgers and his friend Freddie Rhodes, both 18 — tried to rob an Elkhart home and, as they fled, one of the inhabitants, Norman Gary, shot and killed Rodgers. Because Dalton and Rhodes were allegedly in the process of committing a robbery when Gary killed Rodgers, they were both charged with their friend’s murder.

Elkhart Four: Felony murder doctrine recalls infamous case overturned by Indiana Supreme Court

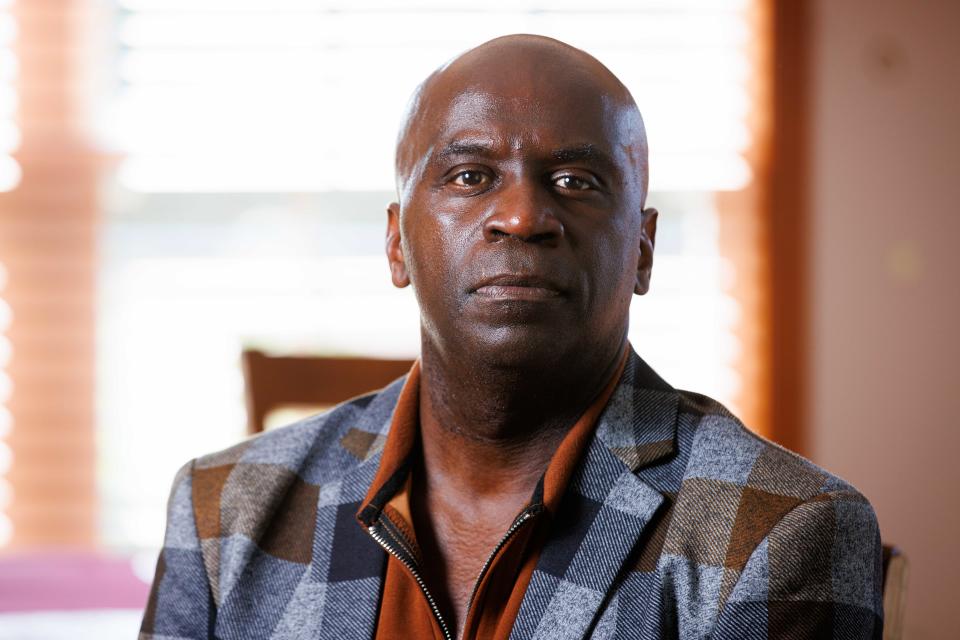

From his initial interrogation through his sentencing, Dalton felt an “unfair” system was stacked against him — an assessment with which his friends and family, as well as multiple lawyers and legal experts, agree. And statistically, the felony murder rule disproportionately locks away young, Black men. Deante Dalton is one of them.

Fatherhood 'the reason for me growing up'

When a reporter asked the Daltons whom to speak with to better understand Deante Dalton as a person, they provided a list of at least a dozen friends, family, mentors, and teachers. Almost everyone responded immediately to an interview request and, during conversations with a reporter, noted that, above all, Dalton was a good kid. (They almost all spoke about Dalton in the past tense.) A really good kid.

His junior English teacher, Jennifer Hershberger, said that he was more studious than most — turning in all assignments, asking questions, and participating in class. “His seat was right in front of my desk, and when I was talking about moving him around he said, ‘Uh uh, I’m staying right here.’”

He didn’t love school, but he didn’t hate it, and he made sure to stay on top of his work so that he could play point guard on his school’s basketball team, where he was happiest. His childhood best friend and teammate, Ajenai Gary, remembers how he once showed up to play multiple games the same day he had his wisdom teeth removed. (Ajenai Gary is not related to Norman Gary.)

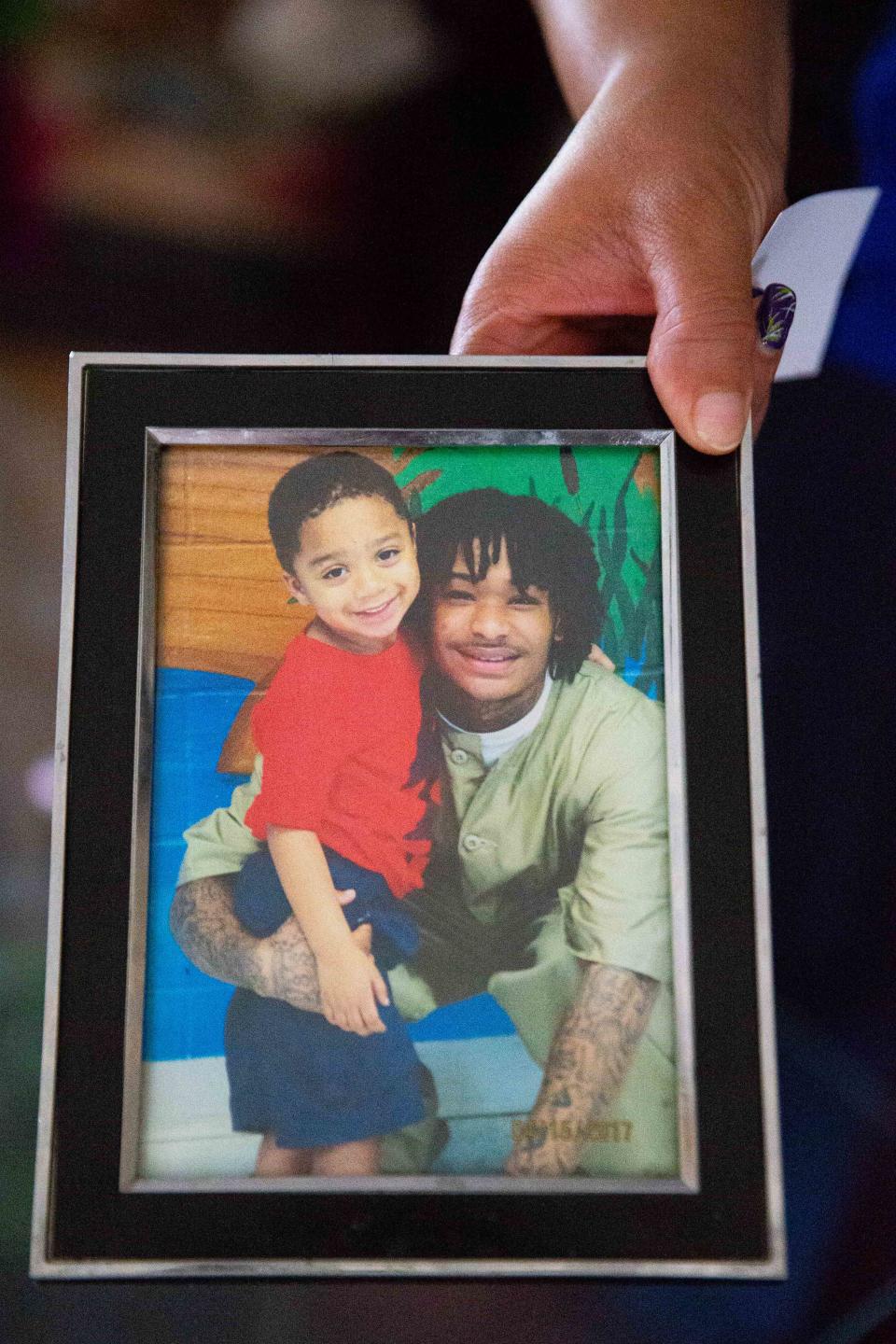

Family and friends all say Dalton kept his head down, flirted with girls, and listened to the adults in his life without talking back. He was also a teen father; his son was 2 when Dalton was incarcerated. His loved ones say they watched Dalton mature rapidly once his son was born. Family friend and mentor Rodney Dell recalls how the two often discussed what Dalton needed to do to become financially stable and take care of his son, like becoming a firefighter or an EMT.

“Had this not happened, he would have done really well in life,” Dell added. “This is a miscarriage of justice.”

When Dalton spoke to a reporter, he seemed the happiest when he spoke about his son, who is now 9. “My son, he’s amazing,” Dalton said, his normally subdued voice growing brighter. “He’s definitely the reason for me growing up and learning a lot of things I had to learn at an early age.”

Juvenile interrogation, with missing recording

Police brought Dalton to the station to be interrogated. They asked his mother, who met them shortly after, to sign papers waiving his Miranda rights to consult with an attorney before answering detectives’ questions.

“I thought I was signing papers to give them permission to talk to my son,” Nakia Dalton said. “I didn’t know that I was signing my rights away.”

Initially, Dalton told the detectives his version of what happened that night: Rodgers and Rhodes came to his house and asked if he wanted to smoke marijuana in South Bend with some friends. He obliged but told them he had to be back before his mom came back from work, as he was babysitting his younger sister and wasn’t supposed to leave. On the way back, Rhodes and his cousin wanted more weed, so they took a detour to a home they believed had a stash. Rodgers said that Dalton, the youngest of the group, should stay in the car. So he did. “All I remember is hearing nonstop gunshots and seeing Rhodes come and thinking in my head, ‘where’s my cousin?’” Dalton said.

But at some point, the story shifted. According to Dalton, he was coerced into a false confession where he told the detectives that, instead of waiting in the car, he was actually inside the home, holding a woman on the first floor at gunpoint while Rhodes and Rodgers went downstairs.

The detectives said “we know this, know that, this is not what you said, we know this to be true,” Dalton said. “They slapped a notepad in front of me with a signature on the bottom saying you did this and did that. A lot of mental games.”

In an ideal case, Dalton’s claim (or the detective’s assertion that the confession was fair) could be verified by looking at the audio and video of the interrogation, which, according to the trial transcript, was cited by the prosecution. Such a video was never presented during the trial, however. In fact, the Elkhart County Public Defender’s office reported no record Dalton’s attorney, a public defender, ever requested the video. Neither Dalton himself nor attorneys from the Notre Dame Exoneration Justice Clinic, who have been reviewing his case for the past two years, have been able to obtain the recording. (“Despite efforts to track it down,” the clinic added).

The only audio file from the police station referenced in the trial is one of Dalton, immediately before the interrogation, talking to himself in the room. “I don’t know what I’m even here for,” he said. And then, seconds later, “You gotta be kidding me, man,” before he stood up and began knocking on the closed door.

According to Riya Saha Shah, Senior Managing Director of the Juvenile Law Center — a Philadelphia-based public interest law firm for children — policies that allow for children to be interrogated without an attorney present, even if their parents are allowed to be in the room (which is the policy in Elkhart), lead to false confessions more often than interrogations with counsel present.

“The reason why attorneys are important in interrogations is an understanding of the law and understanding of the consequences,” she said. “Children don’t fully understand what’s happening, and parents don’t fully understand what’s happening either.” She added that because interrogations also involve authority figures and can legally use lying and other coercive tactics, children are especially vulnerable to false confessions. According to The Innocence Project, a group that seeks to exonerate wrongfully convicted individuals, 38% of exonerated juveniles gave false confessions.

Indeed, Nakia Dalton said she “wasn’t in my right state of mind” when she entered the interrogation room, still hysterical and hyperventilating from witnessing the police driving off with her son moments before.

Though there are complaints about how Dalton’s statement and Rhodes’ confession that placed Dalton at the scene were obtained, the combination was enough evidence for the state to charge him with felony murder. Prosecutors alleged that, though Dalton did not discharge the gun that killed Rodgers and injured Norman Gary, he was still inside the house and, while driving away in the car, discharged a gun multiple times that did not injure anyone but easily could have.

The evidence presented at trial in favor of this version of events, according to Dalton and multiple legal experts, was seriously flawed.

Witness relies on 'the slanting of the eyes'

Dalton and Rhodes, despite efforts by their lawyers to separate their cases, were tried jointly, and neither of them testified on their own behalf. Instead, evidence at their July 2015 trial relied on statements from the police officials who interrogated the pair and inhabitants of the home at the time of the robbery.

Beyond Rhodes’ confession that placed Dalton at the scene of the crime, Dalton was otherwise identified during the trial as being present by only one woman in the house. “I really wasn't for sure at the time, but after everything happened,” she said during the trial, “those eyes. I've always loved his eyes even when he was younger. I knew it was Deante.”

“You could see the whole eye feature,” she said, noting that the person was wearing a mask that concealed the rest of their face. “You could see how the eye slanted. That was very distinctive for me was the -— you know, the slanting of the eyes.”

In a detective’s affidavit from days after the botched robbery occurred, they write that the woman who identified Dalton during the trial initially identified only Freddie Rhodes as being present — the other two people she said only were “black males.” Gary, the inhabitant who was shot, also said that he did not recognize any of the accused.

Multiple lawyers interviewed for this story said that Dalton’s defense attorney, public defender Clifford Williams, should have objected to the credibility of such a form of identification.

“Certainly, a lot of work has been done in this area about eyewitness identification and how unreliable it is and how our brains play tricks on us,” said Ross Thomas, a lawyer the family hired for Dalton’s appeal. “I think that probably should have been explored more and it was not, because it wasn’t argued very well.”

Zachary Stock, legislative council with the Indiana Public Defender Council, was more blunt. “On the face of it, that seems extremely problematic,” he said. “And assumes a lot of facts not in evidence, such as the breakdown of eye shape in the African American community and if it’s any different than any other racial and ethnic group.”

According to The Innocence Project, incorrect eyewitness identifications have contributed to around 69% of wrongful convictions in the United States that have been overturned by DNA evidence.

Instead of objecting on any of those grounds, Williams, Dalton’s public defender, asked the witness: “In your personal knowledge of folks in the Black community, other … other Black people, have you ever seen slanted eyes?”

“Very few,” the witness responded.

“It's kind of common, isn't it?” Williams pressed.

“Somewhat,” the witness admitted.

Even the witness who claimed Dalton fired the gun out of the car couldn’t definitively say whether it was him who did so, just that it was “the person that had me in the house.” (Dalton and Rhodes accused each other of firing the shots.)

Nakia and Deante Dalton both said Williams, who is now deceased, did a “horrible job.” It’s an assessment that Thomas, Stock, and Shah all agree with. Even the Elkhart Public Defender’s office, when asked if they had audio or video files from the interrogation in William’s old files, responded that not being able to find such information in his files was “not uncommon.”

“I try a lot of cases, and it never appeared to me that his attorney — and I don’t mean to speak ill of the dead — never seemed to me that he had really a strategy, or that he was really prepared to go to trial,” said Thomas, Dalton’s appeals lawyer. “He may have been in that situation, where he really thought ‘we’ll work something out.’ Unfortunately, he’s in a place where they didn’t work a lot of things out.”

At the end of Dalton’s trial, where he was tried as an adult, a unanimous jury convicted him of murder. He was sentenced to 55 years in prison. Rhodes, who was 18 at the time of his arrest, was sentenced to 58 years.

Nakia Dalton remembers how distraught she was when she heard the sentence. “I hollered,” she said. “I ran out the courtroom and ran into traffic.”

During the sentencing hearing, Vicki Becker, who at that time was chief deputy for the Elkhart County Prosecutor's office, argued that Dalton should have to serve even more years.

“Clearly, as a 14 or 15-year-old, he's choosing to have sex and procreate, run the streets, and do whatever he chose to do because he is selfish,” she said during the hearing. “He is more worried about his own happiness than he is about anyone else, and that's a reflection on his character.”

Stock, of the Indiana Public Defender Council, called Becker’s comments “so old-fashioned” and noted that it’s common knowledge that juveniles do not yet have fully developed brains. Beyond common knowledge, it’s also a finding validated by the Supreme Court in cases such as Miller v. Alabama, which holds that juveniles can’t be sentenced to life without parole.

Prosecutor decides charges case by case

Vicki Becker, who was elected as Elkhart’s prosecuting attorney in 2016, agreed to an interview about this case.

“If you engage in something inherently dangerous, you have to understand that there are consequences that may result in serious damage,” Becker said of why the felony murder legal doctrine is necessary. “If you engage in the crime, you have to be willing to accept that there are collateral factors and be held accountable.”

For Becker, accountability in Dalton’s case meant felony murder. Other routes to accountability, though, might have been possible. For example, Dalton could have been charged with accessory to murder or robbery: indeed, in other felony murder cases in the same county, defendants pled guilty to some of these lesser charges in exchange for having the felony murder charge dropped.

Becker further acknowledged that, for her, the decision as to whether or not a juvenile is charged as an adult happens on a case-by-case basis and isn’t determined by the crime itself but by the upbringing of the juvenile.

“If you have an extremely young and sheltered child, that’s a whole different ball game,” she said. “Street-wise, there are 14-year-olds that have more street sense than most adults.” Dalton, she said, was already “making big boy decisions,” and she chalked his conviction up to a “lack of effective parenting” leading to kids “raising themselves and being encouraged to use violence to establish their place.”

Nakia Dalton gave a reporter an equally low character assessment of Becker, who in an unrelated case now faces accusations of prosecutorial misconduct. Becker allegedly elicited contradictory testimony from the same witness in two different legal proceedings.

Prosecutorial paradox: Elkhart prosecutor accused of misconduct for her court arguments contradicting each other

“My son didn’t get a fair chance,” Nakia Dalton said of Becker’s prosecutorial behavior.

Visions of life after release

Dalton has now been incarcerated for over nine years. He talks with his mother and siblings daily and used to visit with his son weekly. Because of the coronavirus pandemic and his son moving to New Mexico, he hasn’t seen him in a few years, though the two talk on the phone often about anything and everything — sports, television shows, and advice on how his son can stand up for himself and take responsibility for his actions.

“That definitely changed me as an individual, being young and going through the motions of learning how to become a great parent for your child,” Dalton said. “When he was a baby and he smiled, I didn’t care about nothing but my son.”

He misses his cousin, Rodgers, who he says was his “best friend.” Dalton remembers him most for his sense of humor, which he deployed to put those around him in a good mood.

When asked about his hopes for when he was released, Dalton was initially hesitant. He used to love building with his hands, he said, and wanted to own a construction business at one point. But as he continued speaking, the words — and aspirations — tumbled over one another. He wants to get his driver’s license, wants to be a barber, wants to get his Occupational Safety and Health Administration card — which many employers require and makes job-seekers more appealing — and, above all, wants to be a great father.

“It’s a tough battle being incarcerated every day,” Dalton said. “It’s miserable, it’s horrible. This is not normal, this is not something that an individual should have to endure. I lived 18 years in the world, and I’ve been locked up for nine years, which is half of the time I’ve been in the world.”

Dalton paused for a moment. “I’m held accountable as if I’m the one who pulled the trigger,” he said. “It just wasn’t fair.”

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Elkhart County prosecutor charged Deante Dalton with felony murder