Images of a starving Palestinian boy went viral. The attention saved him.

Just 4½ months ago, isolated in a barely functioning hospital in northern Gaza, 6-year-old Fadi al-Zant was at death’s door.

The medication he needed to treat his cystic fibrosis was nowhere to be found. He was also starving. As videos of Fadi spread around the world, he briefly became the face of Gaza’s hunger crisis. Then attention moved on.

Before the war began, Fadi was a relatively carefree child living in Gaza City with his mother, father, twin brother and younger sister.

His condition was manageable with the right medication and doctors. He loved ice cream, cars and playing in the yard outside his house. He weighed about 40 pounds.

The war in Gaza has displaced more than 1.9 million people, according to the United Nations. Aid shipments plummeted amid Israeli restrictions, leaving hundreds of thousands hungry, including Fadi, who rapidly declined as his family was forced to move from place to place in search of safety.

Fadi’s condition requires that he consume up to twice the amount of calories of other children his age. It also requires specific medication: an enzyme that helps people like Fadi get nutrients from food. Without either, Fadi began to waste away, his 31-year-old mother, Shaima, said.

She knew her son needed a doctor, but there were none nearby that could help. In March, she scooped up Fadi into her arms and walked toward the only hospital she hoped could treat him, she said.

Two hours later, she found a man with a donkey and cart who took them to northern Gaza’s Kamal Adwan Hospital. But even at the hospital, without the needed supplies, there was little doctors could do to help Fadi.

Gaza-based journalists Osama Abo Rabee and Hossam Shabat visited the hospital to document the deteriorating conditions facing sick children. Fadi stood out as one of the most critical. The journalists then posted their videos on Instagram.

Fadi had lost about half of his body weight by then, weighing just 22 pounds. He cried from chest pain and dehydration. Cystic fibrosis causes thick mucus to clog his airways.

Shaima feared that every time she bathed him, the boy’s protruding bones would snap beneath his sallow skin. “My greatest fear is to lose Fadi,” she told The Washington Post in March.

Abo Rabee’s interview with Shaima and the images of Fadi’s sunken face and emaciated body soon went viral. News organizations used them in stories about malnourished children in Gaza.

On the other side of the world, a 27-year-old medical student in South Carolina was working to save him. Tareq Hailat, the head of the Treatment Abroad Program for the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF), remembers watching on a screen as Shaima lifted her son’s shirt up, revealing his bones. Hailat shared the video with a contact at the World Health Organization. By then it had hundreds of thousands of likes.

Getting Fadi out was a nearly impossible task. The north was the focus of Israel’s initial operations against Hamas after the militant group attacked Israeli communities on Oct. 7. Roads were destroyed. Aid workers feared they would join the dozens of their colleagues already killed if they ventured into that part of Gaza.

Hailat said he coordinated with PCRF workers on the ground and secured an ambulance from the World Health Organization, which communicated with the Israeli government to get access to northern Gaza. He also began contacting hospitals in the United States.

Fadi’s weight kept dropping.

At first, health workers said they could only take Fadi and Shaima. But that would mean leaving behind his twin brother Hamdan, sister Samar and father, Ahmad.

“I sat on the floor and cried until they agreed to take my other kids with me,” Shaima said. “But they didn’t agree to take my husband.”

Ahmad gave his son one last kiss on the forehead. Fadi’s grandmother looked on, tears streaming down her face.

After one night in Rafah, Fadi, his siblings and their mother were evacuated into Egypt on March 24.

Fadi received care in an Egyptian hospital to ensure he gained back some weight and that his lungs were taking in enough oxygen to get on an airplane. Flying can be risky for people with untreated cystic fibrosis.

Meanwhile, Hailat had contacted Northwell’s Cohen Children’s Medical Center and asked if they would take in Fadi. The hospital agreed.

“We felt that we could change his life,” said Matthew Harris, the medical director for pediatric and neonatal critical care transport.

The confirmation came on April 12: Fadi would go to the United States for long-term care. Mother and son were given six-month visas.

“It meant he would get good doctors,” Shaima said. But it also meant more farewells, this time to her children and sister, who would take care of Fadi’s siblings in Egypt.

Fadi became one of eight Palestinian children evacuated by PCRF since Oct. 7 who have received or are currently receiving medical care in the United States.

Since Oct. 7, more than 13,500 requests to leave Gaza for treatment abroad have been submitted, according to the WHO, which supports most medical evacuations out of the enclave. The organization said more than 4,900 patients have been evacuated.

But Israel’s offensive in southern Gaza has hampered evacuations. Since May 7, just 23 patients have been taken out of the enclave, according to the WHO.

On May 5, Fadi and his mother landed in New York.

They went straight to the hospital, a state-of-the-art facility about one hour from Manhattan.

Joan K. DeCelie-Germana, the cystic fibrosis specialist charged with Fadi’s care, described him as “skin on bones.” His stomach was distended - a sign of severe malnutrition. His eyes couldn’t focus.

For almost a month, Fadi was in intensive care. He wore an electric vest that cleared mucus buildup in his airways.

During his time in the hospital, Fadi was like any young boy, focused on playing, DeCelie-Germana said.

“I took him outside in a wheelchair and I was popping wheelies with him,” the doctor said. But long-term, there is a risk of PTSD. “Patients that have had really traumatic hospitalizations,” she said, “anything that you do to them, whether it’s a blood draw or a mouth swab, it’s like they’re revisiting the trauma.”

The hospital and PCRF have committed to covering Fadi’s care there, but DeCelie-Germana estimated the medication he needs will cost about $300,000 a year in the United States for the rest of his life, leaving his future care uncertain.

If he ends up in Egypt, he’ll be able to get at least some of his treatment. But in Gaza, it’s unlikely he’ll receive the care he needs.

Fadi began to develop an appetite again, especially for Pringles and Twinkies. He put on about five pounds in four weeks, DeCelie-Germana said.

He and his mother missed their family in Egypt and Gaza, connecting when they could on FaceTime and WhatsApp. They found comfort in God, praying on a small rug on the hospital floor.

On May 31, after three months of sleeping in hospital beds, Fadi woke up in one for what his mother hopes is the last time.

Doctors and nurses cheered as the nervous boy stepped out of his room, his cheeks pink and his eyes sparkling. He had been quarantined from most visitors because malnourishment had left him immunocompromised.

DeCelie-Germana wheeled a large black suitcase behind him, filled with the medication and high-tech gadgets he will need. He will also have to be seen by a doctor at least once a week.

The grinning boy was delighted by the toy cars and small slide in the playroom of his new home near the hospital.

Once the joy of his release ebbed, the pain of the separation increased.

“My parents aren’t here. My kids aren’t here,” Shaima said. “It’s lonely.”

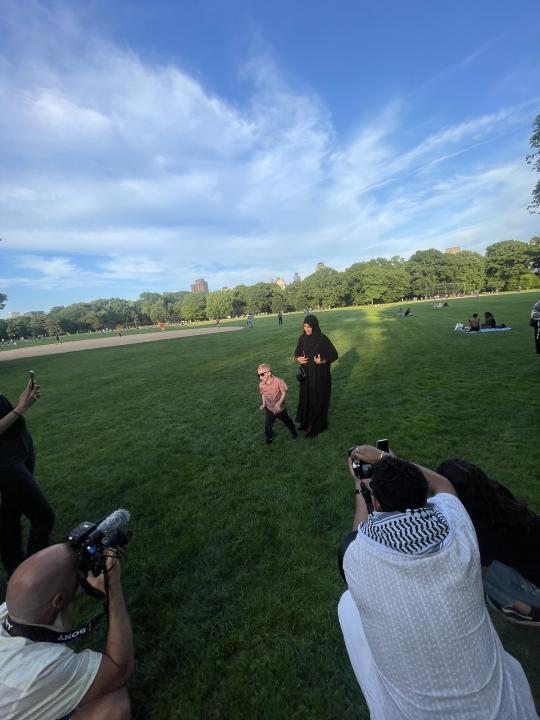

A few days later, PCRF hosted a picnic for Fadi at the Great Lawn in Central Park.

Dozens of people gathered, some wearing kaffiyehs and waving Palestinian flags as they waited to greet the small child they had never met. They brought their children, snacks, home-baked goods and balloons.

Fadi munched on more Twinkies and Haribo gummies. He used his stronger lungs to blow bubbles.

The boy had once again become a symbol, this time of hope. His photo was shared on social media yet again.

His doctors had expressed concern that the big crowd might overwhelm Fadi. But he appeared unfazed in his tinted sunglasses.

“I had so much fun,” he told Hailat when the picnic was over. “I want shawarma.”

Related Content

Migrants from China ‘walk the line’ to U.S. border, testing Biden and Xi

They have jobs, but no homes. Inside America’s unseen homelessness crisis.