Justice Scalia must be rolling over in his grave at the Supreme Court gutting Chevron | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

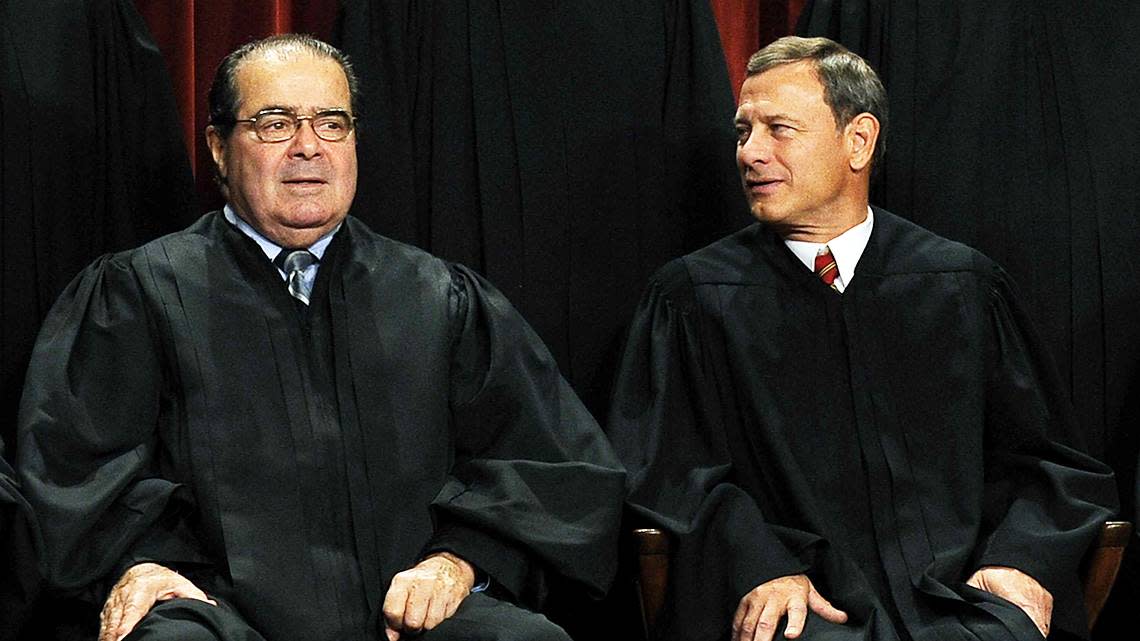

Last month, Chief Justice John Roberts’ Supreme Court made a major ruling that will affect how federal agencies are able to establish regulations. In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the court abandoned the two-part administrative law test established in 1984 in Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council. The decision will have significant impacts across government related to the environment, workplace safety, unfair labor practices, communications, elections, financial markets and health care.

According to Chevron’s first prong, a reviewing court must determine whether Congress has “directly spoken” on the underlying issue regulated by a federal agency. If so, the court “must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress.” But “if the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue,” Chevron’s second prong requires a reviewing court to respect the agency’s construction of the statute if it is reasonable.

Chevron was dutifully followed by federal judges for 40 years and cited as a benchmark of judicial restraint, since the specialists who work in federal agencies (such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration) have the necessary training and expertise to make policy decisions.

Roberts, who wrote the Loper decision, admitted that his former colleague and ardent defender of originalism, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, was “an early proponent” of Chevron. However, Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that Scalia later criticized and “began to express doubts” about Chevron, which is simply not true. Not only did Scalia attempt to expand Chevron deference during his nearly 30 years on the Court, but 25 years after the decision, he called it a “watershed.”

In a famous 1989 speech at Duke University, Scalia defended Chevron based on practical realities and the presumed or actual intent of Congress. “Congress,” Scalia remarked, “now knows that the ambiguities it creates, whether intentionally or unintentionally, will be resolved, within the bounds of permissible interpretations, not by the courts but by a particular agency, whose policy biases will ordinarily be known.” In fact, Scalia defended “an across-the-board presumption” of deference rather than the “statute-by-statute” evaluation that preceded Chevron.

During his time on the court, Scalia criticized his colleagues if they did not adhere to Chevron deference. In 1987, he chastised Justice John Paul Stevens — who wrote Chevron — for suggesting that the court could substitute its own judgment for that of the agency whenever it was able to determine the proper interpretation of a statute. Scalia maintained that such an “approach would make deference a doctrine of desperation, authorizing courts to defer only if they would otherwise be unable to construe the enactment at issue.” “This,” according to Scalia, “is not an interpretation but an evisceration of Chevron.”

Courts should defer to regulatory agencies

Scalia defended expansive interpretations of Chevron. In 2001, he filed a solo dissent when his eight colleagues held that deference did not apply to informal agency constructions of law, such as policy statements, opinion letters, manuals, enforcement guidelines, and court briefs, because they did not carry the “force of law.” Scalia believed both formal and informal agency decisions should receive deference from the courts, and predicted that the consequences of the court’s decision “will be enormous, and almost uniformly bad.”

Scalia also wrote the court’s 2013 decision extending Chevron to agency interpretations of their own jurisdiction. Referring to the “now-canonical” two-part test of Chevron, Scalia found no reason why courts should not defer to agency interpretations of their own jurisdiction. “The false dichotomy between ‘jurisdictional’ and ‘nonjurisdictional’ agency interpretations,” Scalia reasoned, “may be no more than a bogeyman, but it is dangerous all the same.” Responding to Roberts, who dissented in the case, Scalia added, “Like the Hound of the Baskervilles, it is conjured by those with greater quarry in sight.”

“Make no mistake,” Scalia warned, “the ultimate target here is Chevron itself.”

Scalia did reconsider one aspect of Chevron deference toward the end of his judicial tenure: so-called “Auer deference.” In Auer v. Robbins, a 1997 decision Scalia himself authored, the court ruled unanimously that Chevron deference should apply to an agency’s reinterpretation of its own regulations. At the time, Scalia believed this was a logical corollary of Chevron deference, but over time he thought agencies were abusing Auer deference by purposefully adopting broad or vague rules to allow for subsequent changes without notice and comment, thereby raising a distinct separation of powers issue: The power to make rules shall not be combined with the authority to interpret them. Scalia, however, did not change his mind about deference to agency constructions of statutes, in which Congress is ceding power to a coordinate branch of government.

The same year he called for Auer deference to be reconsidered, Scalia wrote the court’s decision expanding Chevron to include questions about an agency’s jurisdiction. During his last full term on the court, Scalia wrote the decision in 2015’s Michigan v. EPA, in which the majority ruled that the EPA’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act was unreasonable based on the two-pronged Chevron approach. In a concurring opinion, his more libertarian colleague, Justice Clarence Thomas, explicitly called for a reexamination of Chevron.

If one accepts the reality of the modern administrative state, which Scalia undoubtedly did, then Chevron deference is an important way to ensure a policymaking role for the executive branch. “If Congress is to delegate broadly, as modern times are thought to demand,” Scalia wrote in 1989, “it seems to me desirable that the delegee be able to suit its actions to the times, and that continuing political accountability be assured, through direct political pressures upon the Executive and through the indirect political pressure of congressional oversight.” “All this is lost,” he added, “if ‘new’ or ‘changing’ agency interpretations are somehow suspect.” Scalia predicted that Chevron would endure, “because it more accurately reflects the reality of government, and thus more adequately serves its need.” As it turns out, Scalia was wrong about that prediction, and it is now the libertarian justices of the Roberts Court who will be making those important policy determinations for the country.

James B. Staab is a professor of political science at the University of Central Missouri in Warrensburg. He is the author of “Limits of Constraint: The Originalist Jurisprudence of Hugo Black, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas.”