Kamala Harris knows exactly what she will do on Jan. 6, 2025

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Jan. 6, 2025, Vice President Kamala Harris is set to preside over Congress and count the electoral votes that will make either her — or Donald Trump — the 47th president of the United States.

And like her predecessor Mike Pence, who resisted enormous pressure from Trump to upend the 2020 election results, Harris says she won’t interfere.

Harris believes that her role in the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress is purely ceremonial — to simply tally up the electoral votes certified by the states — according to spokesperson Kirsten Allen. Though she has long praised Pence’s actions, and Democrats have widely repudiated Trump’s pressure campaign on his vice president, it’s the first time Harris’ team has made that explicit commitment in the run-up to the 2024 election.

Harris’ advisers pointed this week to 2022 legislation signed by President Joe Biden affirming the vice president’s “ministerial” role in the process.

And her view accords with the deeply rooted understanding that the vice president has no constitutional authority to decide which electoral votes to count. Under the 12th Amendment, the vice president’s power is limited to simply opening envelopes delivered by the states and tallying the results.

Yet after the 2020 election, Trump and his allies, in a last-ditch effort to remain in power, devised a fringe legal theory claiming the vice president could unilaterally reject or refuse to count electoral votes, or delay the count altogether.

Pence refused to take those steps, drawing Trump’s fury and inflaming a mob that stormed the Capitol to interfere with the transfer of power. Some members of that mob chanted “Hang Mike Pence” as they ransacked the building on Jan. 6, 2021, forcing Pence and Congress to flee for safety. Harris herself — at the time a sitting senator and the vice president-elect — had left the Capitol earlier in the day and was inside the Democratic National Committee building when a pipe bomb was discovered outside, a fact first reported by POLITICO a year after the attack.

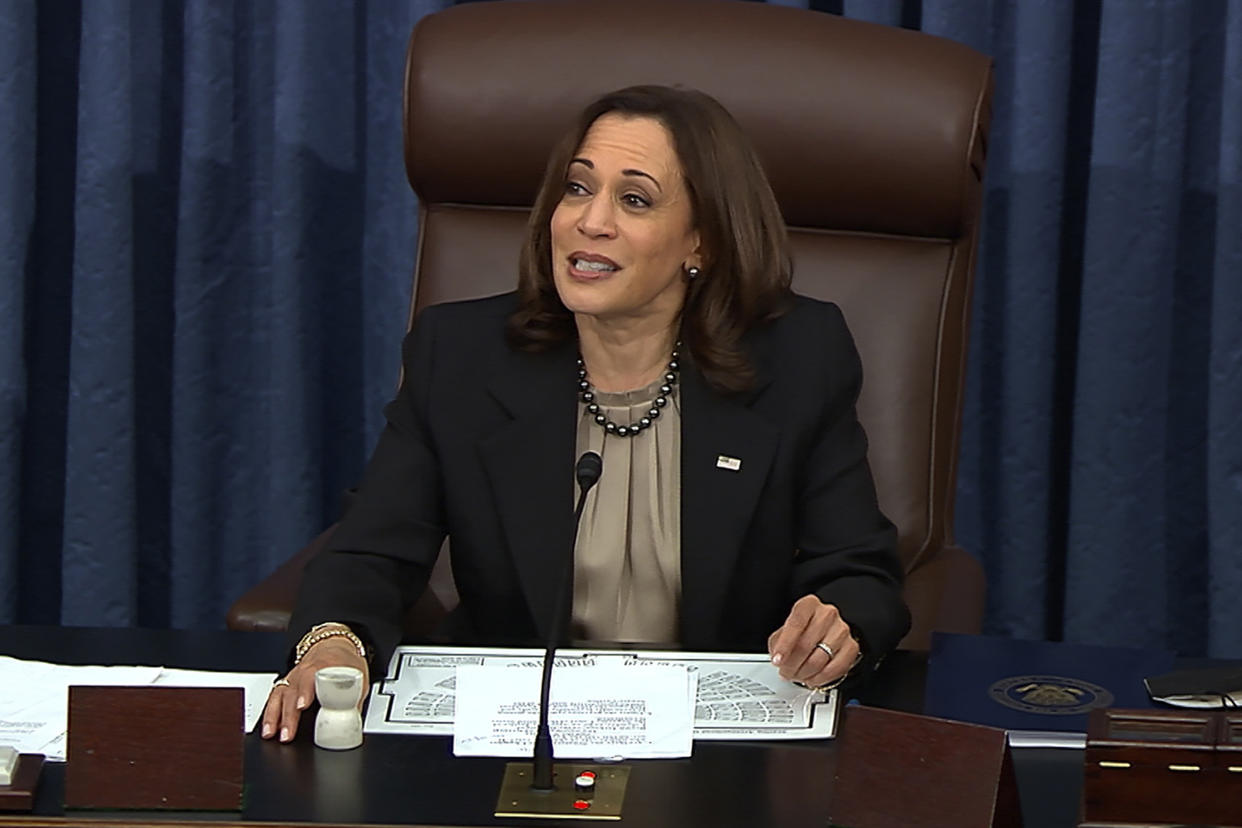

Next Jan. 6, Harris will sit in the same chair Pence occupied — an irony that isn’t lost on the aides and advisers who helped Pence reject Trump’s pressure campaign. They spent the days before Jan. 6, 2021, invoking Harris’ name and urging Trump and his allies to consider what would happen if Pence embraced their fringe proposal — and set a precedent for the future.

“There was never an acknowledgement of the symmetrical situation you could find yourself in if the Democrats were in power,” Marc Short, a longtime Pence adviser who served as his chief of staff, said in a phone interview this week.

Harris’ acknowledgment, through her aides, that she intends to reaffirm the vice president’s traditional role in the electoral vote count carries even greater significance now that she is all but certain to be the Democratic presidential nominee. She is set — like a handful of her forebears — to preside over a process that will confirm her win or loss. In addition to Pence in 2021, several recent vice presidents have overseen their own ticket’s defeat during the Electoral College vote count, including Al Gore in 2001 and Richard Nixon in 1961. George H.W. Bush, on the other hand, presided in 1989 over an Electoral College victory that made him the 41st president.

Trump has never renounced the failed theory about the vice president’s role, even as he and many of his allies face criminal charges over their attempts to deploy that theory and use other tactics to subvert Biden’s victory. In fact, he has pointed to Biden’s decision to sign the 2022 law updating the electoral count procedures as evidence his initial plan was correct. And Trump’s 2024 vice presidential pick, JD Vance, has said he would have obeyed Trump’s commands — and perhaps even gone further — to disrupt the transfer of power in 2021.

The stark contrast by Harris may not be surprising, but it’s significant, said Matthew Seligman, a fellow at Stanford University’s Constitutional Law Center.

“The Democrats have said and seem to genuinely believe that the stakes of this election are extraordinarily high both on policy and the rule of law. Even then, Vice President Harris is saying she won’t seize unconstitutional powers,” Seligman said. “She’s not going to burn the system down in order to save it.”

The details of Trump’s 2020 gambit were defined by attorneys like John Eastman and Ken Chesebro — both of whom have faced criminal prosecution alongside Trump. They argued after the election that Pence had the authority to simply refuse to count dozens of Biden’s electors. Pence, they said, could order that the contest be returned to states with Republican-controlled legislatures to consider whether they should be replaced with pro-Trump alternatives.

Pence and his allies vehemently resisted the effort, in part by noting that it would set a precedent that could be used by none other than Harris should she be in the chair in 2025. For many reasons, including Harris’ recent ascent to become the likely Democratic nominee, they see their decision as vindicated.

“The logical absurdity of the argument that the vice president can choose which slates of electors to accept or reject is that the same proponents … wouldn’t want to consider the consequences of a Democrat vice president,” Short said. “That’s exactly the situation we face now.”

Harris, as vice president, holds the title of “president of the Senate,” a largely ceremonial role that is best known for breaking ties on legislation and executive branch or judicial nominees. But the position also empowers her to lead the counting of Electoral College votes during a constitutionally mandated joint session of Congress that is required to occur on Jan. 6 following the presidential election. Barring any unexpected developments — such as a decision to recuse from the process, kicking it to the Senate president pro tem — Harris is slated to fulfill that duty.

Days before Jan. 6, 2021, Short and Greg Jacob, Pence’s former legal counsel, warned of the risk of empowering Democrats to similarly overturn future elections. It wasn’t their primary point; rather, they contended that Pence simply lacked the authority to take such radical steps to upend the election and that the framers of the Constitution never envisioned vesting such extraordinary power in a single person.

But in testimony to the House’s Jan. 6 select committee, both men said that Trump and his allies declined to grapple with the possibility of a future scenario in which Democrats could turn the tables.

“Are you really saying, John, that Al Gore could have just declared himself the winner of Florida and moved along?" Jacob recalled of a Jan. 4, 2021, conversation with Eastman.

"Well, no, no, there wasn't enough evidence for that,” Jacob recalled Eastman replying. “It wasn't clear how he drew the line that that worked … if indeed it did mean that the vice president had such authority, you could never have a party switch thereafter. You would just have the same party win continuously if indeed a vice president had the authority to just declare the winner of every state … He acknowledged that he didn't think Kamala Harris should have that authority in 2024.”

Eastman told POLITICO this week that his arguments about Harris’ potential power was narrower than Jacob described, saying it was only about whether she could “unilaterally reject electors in a context where there was only one slate of certified electors, and I took the same position against that as I had taken with Pence.”

He noted that some experts had called the vice president’s involvement in the electoral count a “constitutional flaw” and suggested the role should have been granted to the chief justice of the Supreme Court instead. He also noted that a vice president could recuse from the process when there is a “direct conflict,” as some Trump allies proposed Pence should do in 2021.

“Of course, anyone asserting that the VP has such a role would have to concede that my interpretation in 2020 was valid or at least debatable,” Eastman added.

The 2022 law that Biden signed, called the Electoral Count Reform Act, was intended to underscore the “ministerial” role of the vice president in counting electors. The law also makes it harder for members of Congress to lodge challenges to states’ certified electors, and it details procedures for resolving conflicts. The law was the most significant update to the Electoral Count Act of 1887, which laid out the procedures that have governed every presidential election since. The Trump-Harris contest will be the first election certified under the updated law.

Under Eastman’s theory, any laws limiting the vice president’s discretion are unconstitutional, and he urged Pence to refuse to abide by the Electoral Count Act. Investigators and courts have cited that request to violate the law as proof of potential criminality. Eastman argues that there is precedent for vice presidents exercising judgment to count disputed electors, such as Thomas Jefferson’s decision to resolve an issue with Georgia’s ballots in 1801. Other constitutional scholars dispute that premise.

Eastman is currently fighting a California judge’s disbarment recommendation following a months-long series of hearings analyzing his 2020 legal theory.