McCook Lake catastrophe shatters complacency around old flood plans

Damages remain visible in the McCook Lake community on July 3, 2024, after a massive flood hit the area on June 23. (Joshua Haiar/South Dakota Searchlight)

When a record-high surge of water flowed down the Big Sioux River toward the southeast corner of South Dakota last month, local and state authorities activated a flood mitigation plan from 1976.

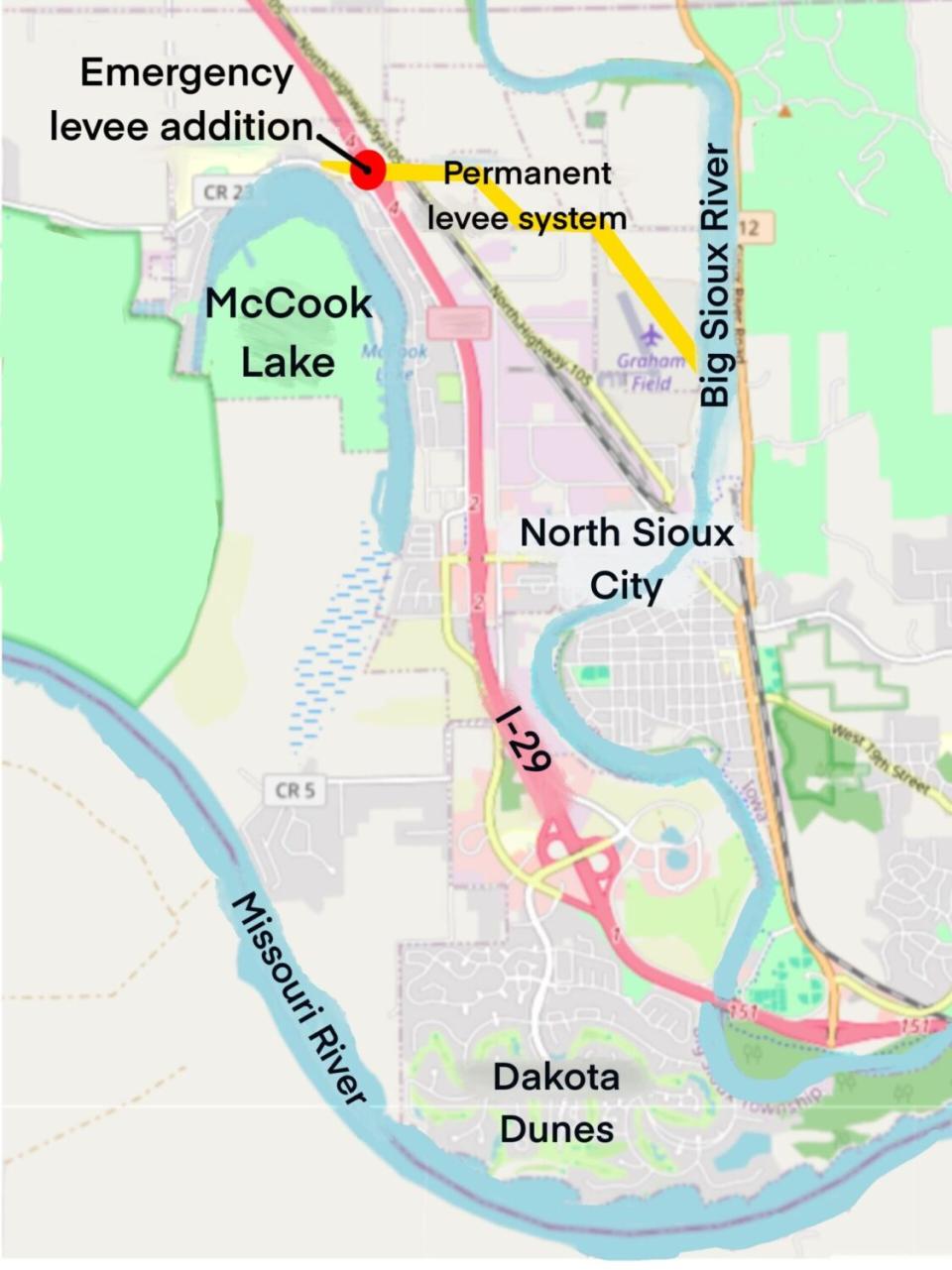

It saved North Sioux City and Dakota Dunes from disaster. But their neighbors in McCook Lake suffered a graphic reminder of how different their community is today than it was 48 years ago.

“Back when there were a few little cabins on the lake that you could replace for $20 apiece, and now there are little McMansions,” said Jay Gilbertson, geologist and manager of the East Dakota Water Development District, based in Brookings.

He said it’s time for an update.

“Most definitely. The idea that a plan drawn up back then would still be applied today is kind of silly.”

Utilizing the existing plan, local and state authorities plugged the area under an Interstate 29 overpass with a sandbag-and-clay levee, to tie in with permanent levees that protect North Sioux City. The system diverted water toward McCook Lake, as intended.

But there was more water than anybody had ever seen before. Instead of causing a manageable rise in the lake, floodwaters slammed into dozens of homes, destroying around 30 of them and carving giant gouges in the land on the lake’s north shore. Fortunately, nobody was killed.

Union County Emergency Management Director Jason Westcott said officials thought the plan would work as it had in the past. Now he says something needs to change.

“We’re having a bad flood every four or five years,” he said. “Our rivers are changing and us humans are doing something to them.”

Some researchers and scientists say the changes are due to a greater frequency of severe rainfall and shifts in land use. And they say mitigation plans have not kept up.

“There’s no question about it,” said Carter Johnson, distinguished professor emeritus of ecology at South Dakota State University. “Mitigation plans, building standards and regulations are based on the 20th century data, which made sense, but we’re changing.”

Mark Sweeney, an environmental science professor at the University of South Dakota, shares those concerns.

“Flood mitigation plans should never be considered static,” Sweeney said. “River channels are in a constant state of change, meaning flood hazards are likely to change, especially over decades.”

The recent flooding began when three days of heavy rainfall inundated southeast South Dakota, southwest Minnesota and northwest Iowa. The McCook Lake community did not anticipate the volume of water that overwhelmed some of their homes on June 23, according to Dirk Lohry, president of the McCook Lake Association.

But in hindsight, the disaster looks like another step in a progression of more frequent, more severe floods affecting the area during the past 15 years.

“I’m 1,000 years old,” Lohry said. “I have now lived through two once-every-500-year floods.”

A changing environment

Warning signs have been accumulating in recent years about changing river flows in eastern South Dakota.

A U.S. Geological Survey report found a 298% increase in streamflow for the James River near Scotland, for example. The report says increases are linked to higher precipitation, urban development, tile drains used under farm fields, and grassland-to-cropland conversion.

The report found “a hydrologically unique trend in the eastern Dakotas that is not being observed anywhere else in the conterminous United States.”

“Specifically, streams in the eastern Dakotas have experienced the greatest increases in streamflow during the last 60 years in comparison to any other USGS gaged stream in the United States.”

When North Sioux City developed its flood mitigation plan almost five decades ago, the highest recorded flow rate of the Big Sioux River in the city was 77,500 cubic feet per second, according to a North Sioux City official who spoke during a July 1 city council meeting. The flow during the recent flooding overwhelmed stream gauges, reaching what some city officials estimated to be 170,000 cubic feet per second.

Severe floods across the Midwest are becoming more common, mostly due to a greater frequency of severe rainfall, said Jonathan Remo, a geologist at Southern Illinois University. He said the “once-every-500-year” title given to some floods is a probability based on historical data.

“But we’re now seeing an unprecedented frequency of major precipitation events,” Remo said. “Something has fundamentally changed, and it’s related, in part, to climate change.”

Around the globe, large amounts of heat-trapping greenhouse gases are being emitted into the atmosphere. Warmer air holds more moisture, which, when it condenses, results in more intense precipitation.

The state climatologist at South Dakota State University, Laura Edwards, has been saying for years that South Dakota’s climate is becoming wetter during wet cycles and drier during dry cycles, translating to more severe droughts and floods.

Carter Johnson, also of SDSU, has studied climate change for decades and said, “We’re seeing changes at rates that have never been observed before.”

He said South Dakota can fund better preparation and mitigation for natural disasters, or spend more on recovery.

“Taxpayers are paying for it either way,” he said. “Insurance rates will continue to go up, natural disasters will continue to happen, and emergency response and cleanup is not cheap.”

Land-use changes

USD’s Sweeney said climate change is the biggest concern for the future, but added that changes to the landscape, like urban sprawl, are also contributing to worsening floods. He said water that would normally soak into the ground like a sponge, slowing its flow rate, now hits asphalt and runs right off.

“We have known for a long time that runoff from asphalt is faster than from grassland,” Sweeney said.

Drain tile — perforated pipe installed under cropland to drain excess moisture — is another factor. When drain tile systems are installed, water that would otherwise accumulate in a field before absorbing into the ground or evaporating is instead channeled into ditches, creeks and rivers.

“Personally, I think tile drains are a slow-motion experiment we are playing,” Sweeney said.

A 2014 study in Ohio found that tile drainage significantly contributed to the amount of water discharged in the watershed. In Iowa, 2016 research indicated that tile drainage significantly alters streamflow, contributing 30% more water to the observed streams during precipitation events.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

Converting grasslands to cropland can also make flooding worse.

Meghann Jarchow, a USD professor of sustainability and grassland specialist, referenced a study showing grassland holds more water than cropland, with or without cropland drainage systems. Prairies have a thick layer of plant material that soaks up rain, which leads to less water draining away.

“We’ve changed so many things in our environment,” she said. “Policies need to keep up.”

Between 2008 and 2016, nearly 5 million acres of grassland were converted to cropland across 12 Midwestern states – including South Dakota – primarily for corn and soybean production, according to a 2021 study. That’s the equivalent of about five Rhode Islands.

Solutions

For the residents of McCook Lake, one priority is clear: They want assurance that their homes will not be “sacrificed” again.

“They’ve got to change that plan,” Dirk Lohry said.

McCook Lake residents called on North Sioux City officials to change the current mitigation plan during a July 1 meeting, suggesting a large ditch be built to direct water to nearby Mud Lake — which does not have a community surrounding it — rather than McCook Lake.

Jay Gilbertson thinks it’s time those “once-every-however-many years” estimates get updated, partly because of how those odds drive design standards for infrastructure like waste management systems and dams.

“You might have to make a system able to handle a once every 50-year event based on historical records,” Gilbertson said. “But 50 might not be 50, it might be 30.”

He said those adjustments could help ensure dams and levees are being built for the environment of the 21st century and beyond, not the 20th.

Federal agencies and state and local governments are all responsible for updating design standards to reflect current climate data.

Zoning laws could also be updated to illustrate flood zones more accurately, Gilbertson said, restricting development in high-risk areas, and ensuring adequate park and wetland space to help absorb floodwaters.

In 2020, State Climatologist Laura Edwards wrote about increased flood risks in South Dakota, highlighting how many properties are at greater risk than currently indicated by Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood plain maps. Multiple McCook Lake residents told South Dakota Searchlight they do not have flood insurance, because of the expense and because they’re not in an area designated by FEMA as requiring it.

Sweeney said the accuracy of flood plain maps is critical, as are local government decisions about what development, if any, is allowed.

“We will never be able to eliminate flood hazards as long as the government allows people to build in flood plains,” Sweeney said.

The post McCook Lake catastrophe shatters complacency around old flood plans appeared first on South Dakota Searchlight.