Memory Lane: Palm Beachers' health-care generosity dates to 19th century

Before Palm Beach society’s influence and largesse pumped cachet and capital into the area’s first major hospital, a tiny “emergency” medical facility preceding Good Samaritan came into being thanks not only to the island’s generosity but a standard-setting doctoring tradition that began before the rich arrived in droves here.

By the time Standard Oil partner and Florida developer and railroad tycoon Henry Flagler came and built two resort hotels in the 1890s — including the oceanfront Breakers — pioneers had been privy to health care by devoted physicians who traveled to patients by boat.

The first doctor arrived in 1881. After Dr. Richard B. Potter — who treated anyone in need, including members of the Seminole tribe — other physicians followed and also called on midwife Millie Gildersleeve, a Black pioneer, to aid with women’s health care.

Once Flagler’s two Palm Beach resort hotels, which also included the now-gone behemoth Royal Poinciana on the lake, were built in the mid-1890s, there still was no hospital, but health care opportunities continued to slowly expand.

After all, now there not only were local residents, but winter floods of affluent Gilded Age visitors arriving in their private Pullman railroad cars to enjoy long stays of golf, fine dining, tennis and more at Flagler’s hotels, which comprised a swanky developed swath in an otherwise still largely undeveloped barrier island.

And what of the hundreds of bellhops, maids, groundskeepers and others employed at the hotels? Flagler was concerned about their health care, too.

“We ought to have a place where we can send sick employees,” he wrote in a 1902 letter to one of his chief hotel executives, according to information the Flagler Museum shared earlier this month with the Daily News about Flager’s hotel-related health care initiatives. “We have a thousand servants, more or less, in the two houses (hotels) here, and with the want of proper care, which such people usually exercise, we are apt to have more or less sickness.”

Months later, Flagler identified a potential site for a medical building behind the Royal Poinciana and the facility “it is presumed” served others in the community, Flagler Museum officials noted, adding that Flagler also aimed to build another medical facility to the east (near the ocean/The Breakers) but it is unclear if that one was constructed or not.

For the wealthy guests staying at Flagler’s “electrified” hotels, each property typically employed a “house physician,” according to early maps and hotel-layout schematics.

In fact, all of Flagler’s major Florida hotels — from St Augustine’s Hotel Ponce de Leon (now Flagler College) to the now-gone Royal Palm Hotel in Miami — usually boasted resident physicians at one time or another with on-site offices open during the hotels’ winter season.

One of the earliest resident hotel physicians in Palm Beach at Flagler’s Royal Poinciana, for instance, was Dr. Frank Fremont-Smith, who by late 1901 was living with his wife in an eight-bedroom shingled house in Palm Beach called Lotus Cottage.

Lotus served as a guest house, of sorts, for the marble-pillared mansion Flagler built as a wedding gift for his third wife, Mary Lily Kenan Flagler. The Flaglers wintered at Whitehall, now the centerpiece of the Flagler Museum, for more than a decade. Fremont-Smith’s quite-social wife, who enjoyed playing the piano, often held teas at Lotus Cottage, according to turn-of-the-20th-century news reports.

Another medical doctor — a cousin of Mary Lily Flagler’s — replaced Fremont-Smith as the Royal Poinciana’s hotel physician. But before long, Dr. Owen Hill Kenan instead became Flagler's personal physician and he was the one who attended to Flagler in his last years before his 1913 death. In May 1915, Kenan would survive the sinking of the Lusitania off the southern coast of Ireland.

Meanwhile, local Palm Beach residents during the Flagler era weren’t only served by “Doc” Potter, the first physician who’d arrived in 1881. Other physicians arrived later.

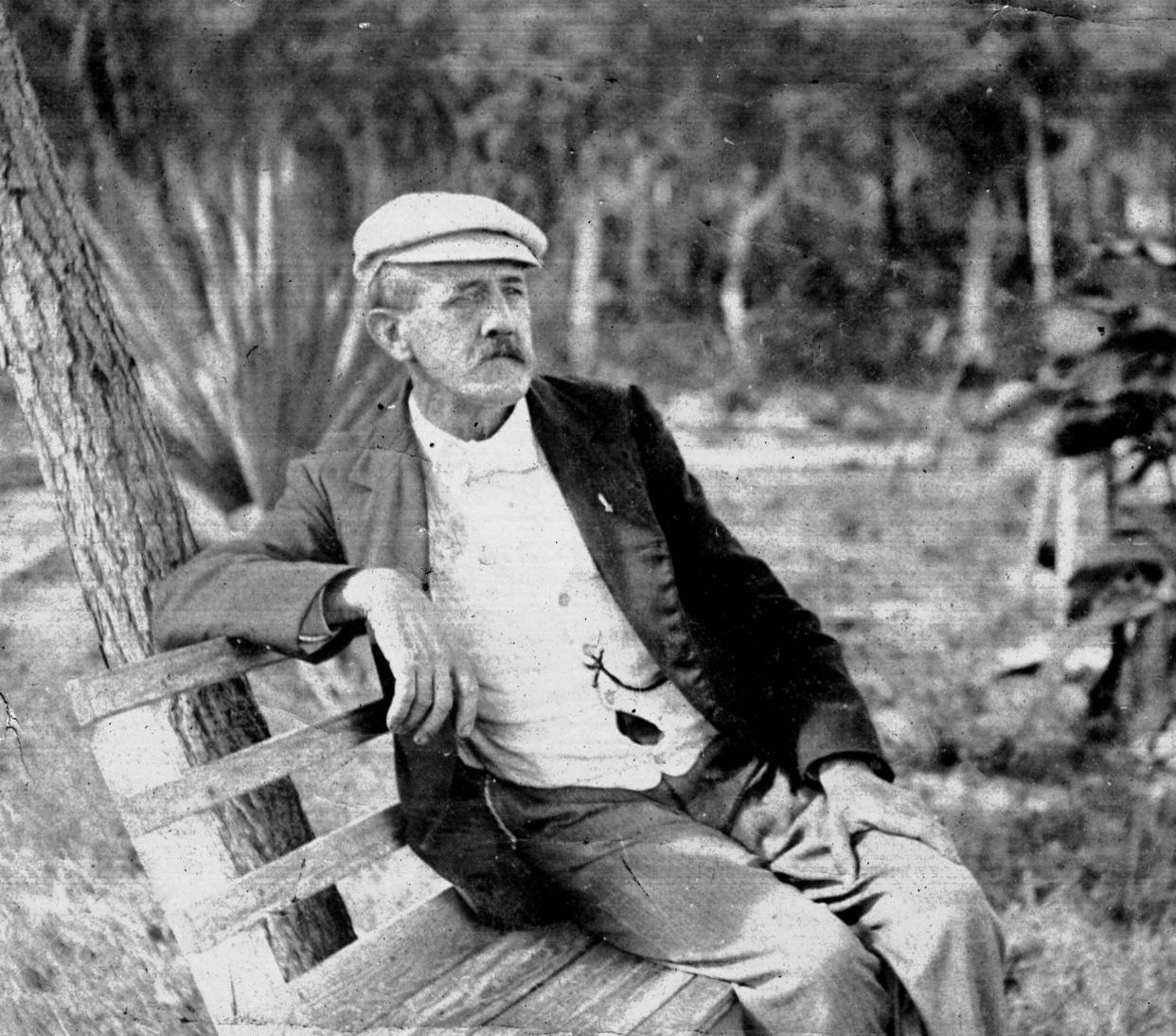

Despite challenges, word of the island’s warm climate and plentiful food (fish and game a-plenty) spread quickly to other parts of the country and, as more settlers arrived, so did another physician, Dr. Henry Clinton Hood. Soon after he came on the scene in 1889, he married Mary Minna Brelsford, the sister of two influential pioneer-businessmen in Palm Beach who’d established the first general store before branching out into other businesses.

Though his work, like Potter’s, often required traveling miles away to serve patients who’d settled in the area, Hood’s home and office was at 2 South Lake Trail in Palm Beach. By the 1890s, that was just south of Flagler’s lakefront hotel and Flagler’s Whitehall mansion. Called Satinwood Cottage, Hood’s home was “a rambling three-storied wooden structure,” the late Judge James Knott, the 1957-1969 president of the Historical Society of Palm Beach County, once recalled. “There were rocking chairs and hanging swings on the wide porches which hugged the house on three sides. Toward the rear, an old ramshackle wooden building housed the servants.”

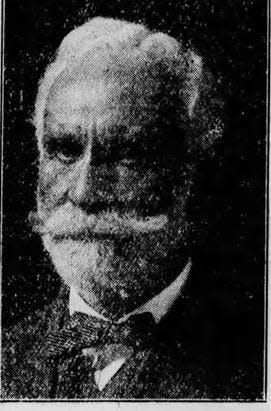

In 1910, when another physician, Dr. Leon Ashley Peek, joined the community, he was shocked to discover there was no hospital. He and Hood (Doc Potter had died in 1909) began lobbying for one and, considering West Palm Beach rapidly was growing, it made sense to locate it there, but within close proximity to Palm Beach’s access to the budding city.

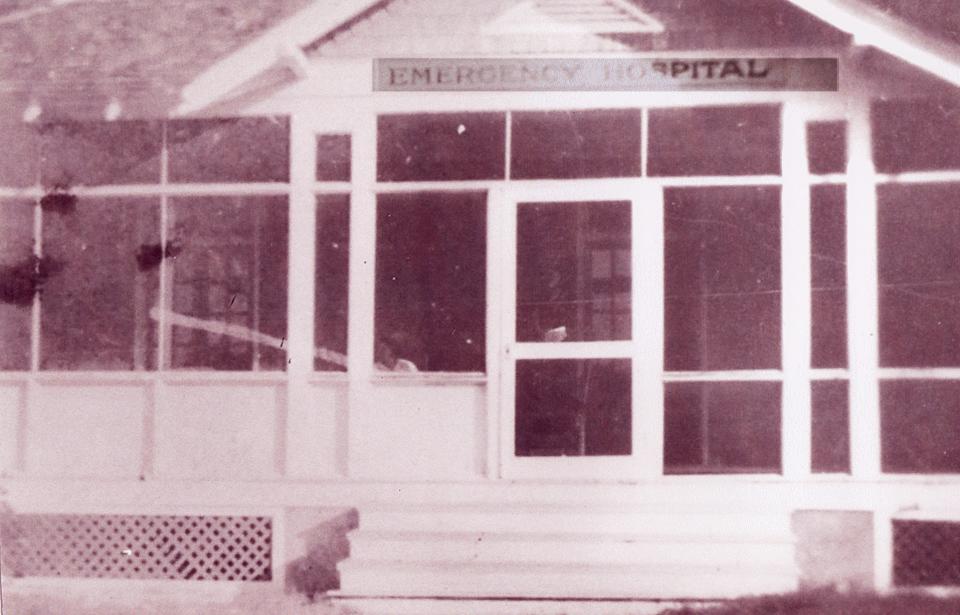

Before his 1913 death, Flagler donated the necessary land for such an “emergency” medical facility. In 1914, Emergency Hospital opened on Third Street (just north of Clematis and Banyan streets) near Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway tracks. It included an operating room, a nurse’s room, a kitchen and a bathroom. A tent in the backyard sometimes served as sleeping quarters for nurses.

“The weekly charge for patients was left to the discretion of the hospital’s managing committee, but the minimum rate was not less than $3 a day,” according to the Palm Beach County Medical Society.

Between fast-growing Palm Beach and West Palm Beach, Emergency Hospital wouldn’t suffice for long, especially not in the minds of the wealthy, who by 1919 were commissioning custom mansions in Palm Beach instead of bunking at luxe island hotels.

One of them was Marjorie Merriweather Post, who became a winter regular on the island long before her famed Mar-a-Lago estate would be completed in 1927.

She spearheaded fundraising galas in Palm Beach, most notably at the Everglades Club, in 1919 for Good Samaritan Hospital, which opened in 1920 with 35 beds at its present location on Flagler Drive. Peek would serve as its chief of staff for many years.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: How Palm Beach pioneered health care for its community