Miami Beach to crack down on homeless residents sleeping outside in August

At a news conference Monday, Miami Beach Mayor Steven Meiner introduced Operation Summer Relief, a month-long homelessness initiative that drew criticism from some advocates who argue city and state laws are unfairly criminalizing unhoused people.

Officials said Miami Beach’s initiative aims to keep individuals from living on public property during the month of August, a period when average temperatures reach their highest. To do so, the city is partnering with homeless outreach services, shelters, health care providers and Miami Beach police.

Meiner stressed compassion and empathy in the city’s approach to homelessness, which includes providing social services such as shelter placement, family reunification and identification assistance.

But he also made clear that the city is taking a tough-on-crime approach, driven by a concern for public safety.

“Do not mistake our compassion for weakness,” Meiner said.

The initiative arrives as controversial legislation around homelessness takes root at the city, state and national levels, most recently marked by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling allowing cities to arrest the homeless for sleeping in public.

Miami Beach passed a ban on public sleeping in October, allowing for arrests to be made without warning if the individual declines shelter placement. This carries a penalty of up to 60 days in jail and a $500 fine. Arrests have increased as enforcement of the ban has intensified in recent months.

A similar law signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis will go into effect statewide in October this year. This law prohibits cities and counties across Florida from allowing people to sleep in public.

Critics of the policies argue they unnecessarily criminalize homelessness, making it more difficult for these individuals to obtain permanent housing.

Miami Beach is home to approximately 154 unsheltered homeless people, according to the most recent Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust census. But Miami Beach only manages 86 shelter beds, which are located outside the city in multiple facilities, such as Camillus House and Lotus House. While the city hosts the only walk-in center for the homeless in the county, no shelters are located within Miami Beach itself.

David Peery, the executive director of the Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity, said not all of these 86 beds are regularly available, either.

Shelter placement, meanwhile, remains a complicated solution — not all homeless individuals are interested in shelter. Shelters often strip people of their last remaining possessions, which can damage their sense of autonomy, Peery said.

For others, shelters can leave them vulnerable to theft. Shirley Armstrong, who lives on the streets of Miami Beach, said she had her birth certificate and Social Security card stolen in a shelter in the Bronx, NY.

“You lose everything,” she said on Monday.

The 68-year-old has been homeless on and off since 1990 and arrived in Florida from New York in 2021. She said she spent some time sheltered by Miami’s Salvation Army but left in May, after her roommate filed a grievance report.

Now, Armstrong sleeps wherever she can. She applied for food stamps at the library last week, she said, but was told she’d have to wait a month.

Because not all homeless people accept shelter, the city “always [has] ample beds,” Meiner said.

Additionally, Miami Beach works to provide other services to support the function of shelters as a transitional place using a care coordination model, according to Director of Housing and Community Services Alba Tarre.

“It is not meant to be long standing. So we’re constantly working with clients to get them to that next chapter in their journey,” Tarre said.

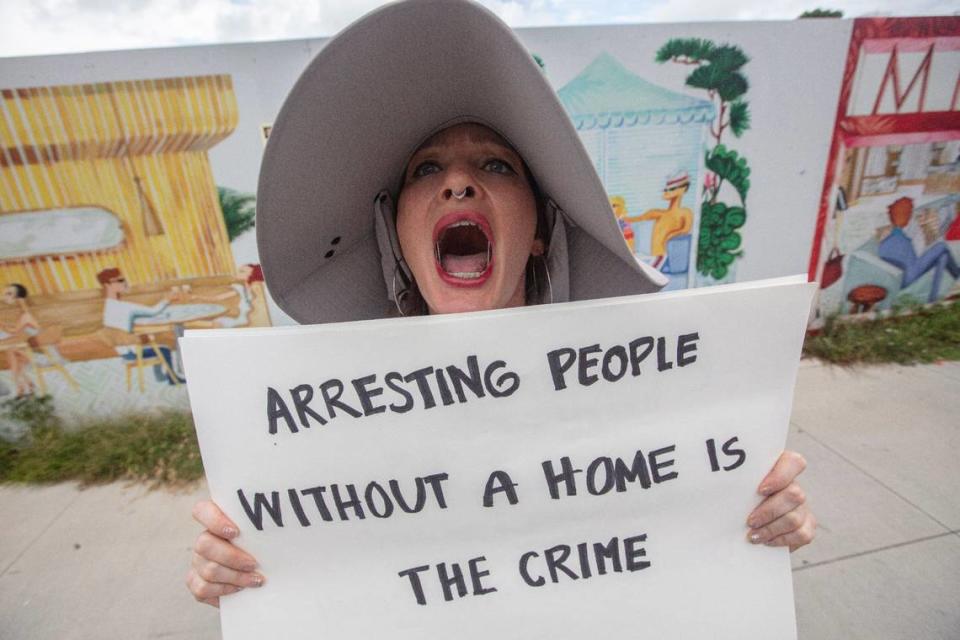

Protesters gathered to oppose ‘cruel’ policies in Miami Beach

Advocates across the street from City Hall were calling for a different approach. Four protesters assembled Monday afternoon to voice their opposition to the city’s policies regarding homelessness, which Peery called “cruel, inhumane and futile.”

“It’s horrible, and it won’t work,” Peery said of the city’s public sleeping ban. Peery’s organization, the Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity, hosted Monday’s protest.

In Miami Beach, unhoused individuals make up 40% of arrests, despite making up less than one percent of the city’s population, Peery said. Arresting people for sleeping in public diverts police resources that could be used to address more serious crimes, he added.

Instead of jailing unhoused people sleeping in public, Peery and the other protesters advocated for a housing-first approach.

This means giving unhoused individuals permanent housing without conditions. Kat Duesterhaus, an activist at the protest, said this approach is cheaper than putting people in jail and is “backed by research and compassion.”

At the protest, Duesterhaus held up a sign that read, “Housing costs less than handcuffs!”

Peery said he believes many Miami Beach residents believe “dangerous false narratives” about homelessness, including that people are homeless because they turn down the resources offered to them or because they are “personally irresponsible.”

Poverty, not criminal intent, is to blame for homelessness, Peery said. He added that the trauma of living on the streets often leaves people “in a fog,” unable to focus on anything but surviving each day.

Having safe, permanent housing means these individuals would not have to worry about being robbed or arrested while living on the streets. This means they would be better able to take steps to get back on their feet, Peery said. That’s why he said he thinks the city needs to buy apartment units to house its homeless population, rather than placing them in shelters or arresting them.

Duesterhaus led chants that could be heard at the news conference across the street, which was being held outdoors on the third floor of city hall.

“Being poor is not a crime,” Duesterhaus shouted, along with the other protesters.

“That is absolutely a true statement,” Meiner said in response to the protesters’ chant. “But we are offering you the help, and we are going to protect our residents. We are going to protect public safety in this city.”